Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoWhere Are the Kids? Georgia has spent over $10 million to track down unaccounted-for schoolchildren post-COVID. Will the trend continue?

An aerial view of Cottrell Elementary School in Dahlonega, GA. (Credit: Breaux & Associates / Architects)

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is part of an ongoing series looking into statewide issues impacting Georgia’s public and private schools. If you have an idea that you would like our reporters to look into, contact us at [email protected] or [email protected].

Lumpkin County School Superintendent Robert Brown first noticed something was amiss in the fall of 2021.

Enrollment in the district’s high school, middle school and three elementary schools had dropped from about 3,840 in the spring of that year to 3,740 in the fall. It was a precipitous drop for the small, rural north Georgia county, famous for being the site of America’s first major gold rush.

“So 100 students immediately were not here. You go to the data and try to dig in a little bit and [you ask], ’What’s going on here’?” Brown recalled. School officials soon discovered there were 50 fewer kindergarteners than the previous school year. But that still didn’t explain the remaining 50 missing students.

Lumpkin’s enrollment numbers have bounced around over the last couple of school years. Today, enrollment is at 3,805 students, still down by 50 students, Brown said in early August. The decline has impacted the school district financially over the last three years.

“We missed out on $1.5 million in state [Quality Basic Education, or QBE] earnings and we use our federal ESSER [Elementary and Secondary Emergency Relief] money to make up the difference,” Brown said.

More than 15,000 students were reported unaccounted for in over 50 school districts in Georgia at some point during the last school year.

The unprecedented absence emerged in an end-of-school year report submitted to the Georgia Department of Education in May by Graduation Alliance, a Salt Lake City, Utah-based firm that works with at-risk kids. Since COVID, the company has spent the last few years helping more than a dozen states, including Georgia, find students who aren’t in public or private school and who aren’t being home-schooled.

The issue has stumped state and national education leaders.

“Trying to recapture those kids or figure out where they are [is hard],” John Zauner, a retired Carroll County schools superintendent, told State Affairs. “Many of the school districts feel somewhat responsible for those children but they’re just unable to track them.”

Zauner is now executive director of the Georgia School Superintendents Association, where the issue has come up among members of the organization that represents Georgia’s 180 school districts.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Zauner said.

Georgia has spent $10 million trying to track down the missing students and get other at-risk kids back to school.

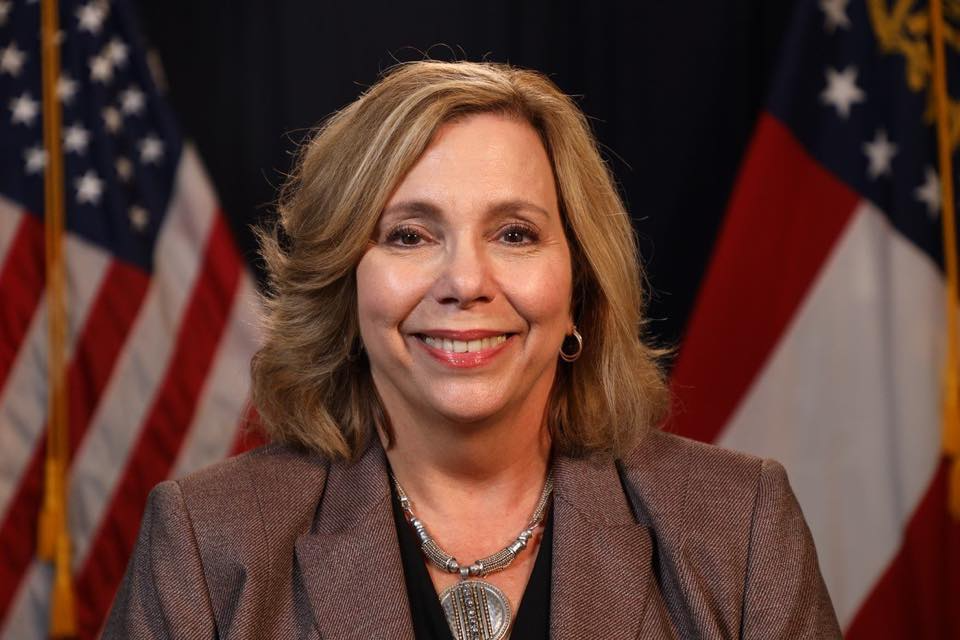

“We’ve spent that much money because we think it’s a priority to try to contact as many students and families and get them re-engaged,” Bronwyn Ragan-Martin, deputy superintendent for the Georgia Department of Education’s Office of Rural Education and Innovation, told State Affairs.

A national issue

During the three school years affected by the pandemic, state public school enrollments declined while the number of students in private school and home study environments increased, according to Matt Smith, director of policy and research at Georgia Partnership for Excellence in Education. Meanwhile, school districts across the country also grappled with unaccounted-for students.

Between the fall of 2019 and the fall of 2021, enrollment in public schools in Georgia dropped nearly 1.5% from 1.72 million to 1.69 million. Private school enrollment during that time rose over 1.6% to 100,246 while homeschooling skyrocketed nearly 17% to 91,142 students.

Georgia enrollment trends were consistent with those seen in other states during the pandemic, Smith noted.

In the first full school year after the onset of COVID, K-12 public school enrollment in the United States fell by more than 1 million students, Stanford University economist and education professor Thomas S. Dee noted in an essay for the Urban Institute in February. The losses continued through the 2021-22 school year.

“We know little about where these students went during the pandemic and what learning environments they experienced,” Dee said.

Now as a new school year gets underway, Georgia educators face the prospects of untold numbers of school-age children turning up missing — again — from public school rolls, and who are unaccounted for elsewhere.

Georgia law requires students to attend public or private school or a home study program starting at the age of 6 until their 16th birthday. More than five unexcused absences from school constitutes truancy. If the child is charged with truancy, the parent or guardian could face penalties.

But the rules appear to have fallen by the wayside due to the pandemic.

When asked if this was an issue of truancy, Ragan-Martin responded: “Well it depends on the age. We would normally have our protocols in place. After so many absences, we start referring parents to law enforcement. During the pandemic, law enforcement weren’t going to go after these families. So that sort of lax attitude was definitely warranted at the beginning. Who was going to go after any family during the pandemic when somebody could be sick?

“Even a year in [to the pandemic], it was hard to get back into those protocols. First of all, the court system was so backed up, that it would have been difficult to start handling those cases again,” she added. “ I think all of it has kind of compounded the attitude of, ‘Well, it doesn’t really matter right now.’ So it’s been hard for it to matter again.”

Chronic absenteeism, student disengagement and dropout has always been a concern of school administrators. But the ongoing, massive, unexplained post-COVID exodus of students has stumped many state and national education leaders. Disengagement includes unaccounted-for students as well as those kids whom officials knew weren’t attending any school, Greg Harp, chief development officer at Graduation Alliance, said.

“Clearly, we’ve never had that type of disruption in our nation, at least not in my lifetime,” Harp told State Affairs.

That type of disruption ultimately could impact funding for Georgia, the nation’s 15th largest school system, especially when the ESSER federal pandemic relief funding ends after this new school year. All told, Georgia has received three rounds of ESSER funding totaling nearly $6 billion.

“School systems have had the funds [now] to be able to hire more counselors, more social workers. They’ve had all of those things to do the outreach they’ve needed to do and to provide the support for the students and the families,” Ragan-Martin said. “My concern is after next year, what happens? [What will be] the funding impact because of fewer students, and the loss of the ESSER funds? How are we going to face that?”

State Department of Education officials have teamed with the Georgia Partnership for Excellence in Education to look at the best way to use the current ESSER money. That project ends in June 2025.

Future workforce implications

If the problem of unaccounted-for children becomes protracted, experts worry that it will lead to an educational decline in the workforce and severely impede the future supply of workers in a state that has repeatedly been recognized by Area Development magazine as the number one state for business.

Aside from having a greater segment of the workforce with deep deficiencies in math and reading skills, there will be other deficits, Dee noted.

“There’s a lot of socialization to structure and working with others that occurs in school that is valued in the labor market,” Dee said.

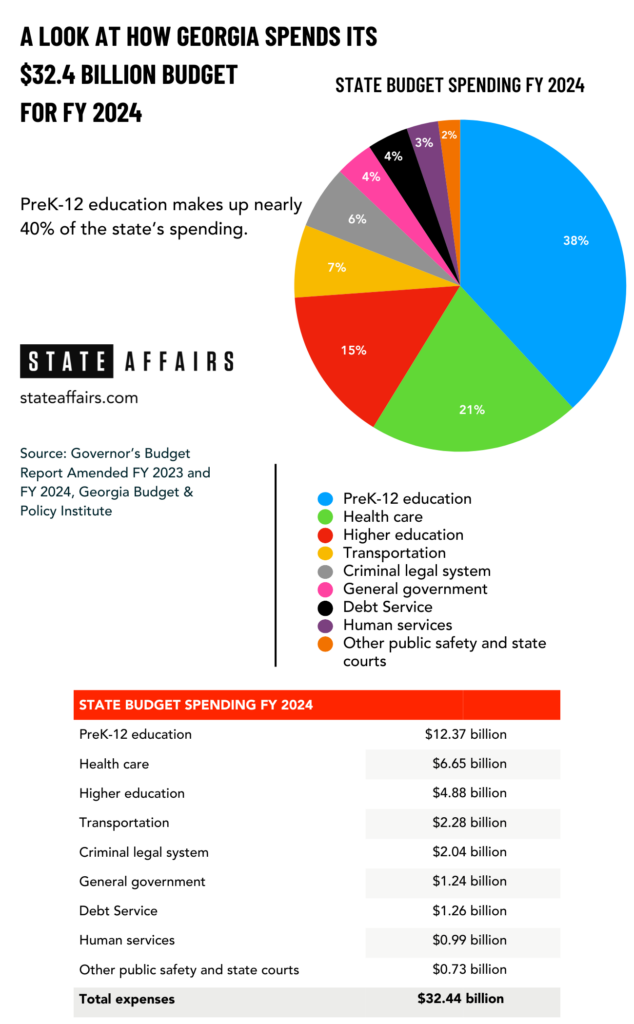

School districts receive state money based on the number of children attending school. In fact, the largest chunk of Georgia’s $32.4 billion fiscal year 2024 budget goes to pre-K-12 education, accounting for a little over 38 percent of the total state budget.

“Unless we remediate the educational harm of the pandemic, there will be negative implications for the quality of the future labor,” Dee said. “There’s a lot of socialization … and working with others that occurs in school that is valued in the labor market.”

An estimated 230,000 students in 21 states were unaccounted for, according to an analysis of national enrollment data compiled by Dee in partnership with The Associated Press and Stanford’s Big Local News project. The students hadn’t moved out of state nor were they signed up for private school or home-school. The study found some students and their families were still afraid of COVID, were homeless or left the country. Some students couldn’t handle remote or online learning and found jobs instead. Dee’s analysis, from a little over a year ago, found a little over 9,000 of those kids were in Georgia.

Today, exact numbers of unaccounted-for students is anyone’s guess. Tracking a student who isn’t enrolled in some kind of schooling is difficult. There appears to be no national database or statewide system that allows states to track unaccounted-for students.

State Affairs talked to an array of state and national education experts, none of whom knew of a central database that tracked students who’ve fallen off the grid.

“We have 1.8 million children in Georgia,” Zauner of the state superintendents’ group said. “So think about that. Nationwide, it would be a massive database to maintain something like that. I’ve not ever heard of anything like that and I’ve been in this business a long time.”

‘Finding Grandma’

But Graduation Alliance’s report may provide the most telling glimpse of the problem in Georgia so far.

The Georgia Department of Education tapped the education services firm in 2021 to find unaccounted for students and other at-risk children through the ENGAGE Georgia Attendance Recovery program.

More than 100,000 students were referred to ENGAGE, which primarily deals with kids who are chronically absent and academically at-risk. It also deals with children who are no longer attending school. The program includes statewide support for school districts and ongoing academic and life challenges coaching support for district-referred students who are chronically absent, academically at risk or no longer attending school.

Some 15,218 students — about 14% — of the 107,000 K-12 students referred by districts to ENGAGE for various at-risk reasons were unaccounted for, Harp said. About 29% of those unaccounted for students enrolled in coaching and participated in attendance interventions, and 12% had moved out of state, graduated or were in private school or were being home-schooled. Some 1,800 were fully disengaged, meaning they weren’t in any school at all.

Despite months of searching — over 1.2 million outreach attempts were made, school officials say, Harp concedes his company’s numbers don’t fully capture the magnitude of the problem. Graduation Alliance worked with individual school districts, not the state.

“We didn’t work with every district. So is there a lack of data and understanding of exactly everything that happened? Yeah, there’s no doubt about it,” Harp said. “Some of this is a data issue. Yeah, we don’t know where they are. That doesn’t mean they’re not in school [somewhere]. That means we haven’t been able to get in touch with them.”

Nonetheless, Georgia education officials have combed the state looking for students.

“We did a statewide push starting with the rural districts first,” Ragan-Martin said. “And then when we had all the rural districts fill up as many slots as they did, then we opened it up to the larger districts. They had a ton of disengaged students.”

Because of the transient lifestyle of many of the students, Graduation Alliance’s enrollment counters used phone, emails, regular mail, text messages and emergency contacts to track down students. But largely to no avail.

“I like to call it finding grandma,” Harp told State Affairs. “If you find their grandma, you’ll find out where the student is, even if they’ve moved around.”

‘They were just home’

Brown, the Lumpkin County School superintendent, says what has occurred over the last few years is unlike anything he has seen in 28 years in education.

Due to the shortfall in students, the district has had to readjust in some areas. For example, the extra kindergarten teachers hired for the 2020-21 school in anticipation of a large kindergarten class were moved to other areas in the district, Brown said.

Come January, Brown said the school district will face some tough decisions: trim the budget, reduce staff and services provided to students, or tax local citizens at a higher level.

“This was the first time I’ve ever experienced a sudden reduction. It was unforeseeable and unplanned,” he said.

Ragan-Martin faced similar problems. In the fall of 2021, she was superintendent of Early County Schools, a 2,000-student system in southwest Georgia near the Alabama line. An unusually large number of students weren’t returning to school either. And no one seemed to know where they were.

“It was way more than our normal families who had attendance issues,” Ragan-Martin recalled.

The school system’s director of student services along with school counselors made hundreds of visits during the 2020-2021 school year, knocking on doors trying to find out why kids weren’t in school.

“They were just home,” Ragan-Martin said. “The parents would say they’re not coming back.”

Enrollment in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools in Georgia

Here’s a look at enrollment over the last six years. The 2021-22 school year was the first full year that Georgia K-12 students returned to the classroom after the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2011 and 2017, total statewide enrollment grew from 1.68 million to 1.76 million. Enrollment has see-sawed since. Enrollment is projected to drop 1.2% over the next eight years.

Year | Fall Enrollment

2023 — 1.743 million

2022 — 1.743 million

2021 — 1.740 million

2020 — 1.730 million

2019 — 1.769 million

2018 — 1.767 million

She got emails from people accusing her of “setting up children to get sick and even die.”

Ragan-Martin soon learned how widespread the problem was.

In October 2021, she joined the state Department of Education where she was appointed to head an office created to deal with, among other things, the increased number of unaccounted-for students in rural areas.

State superintendent Richard Woods and Chief of Staff Matt Jones, both from rural districts, created the Office of Rural Education and Innovation using federal pandemic relief money. The office teamed with Graduation Alliance in the spring of 2022 to find the missing students.

State education officials initially thought the unaccounted for children were a rural problem but quickly learned children were missing from classrooms all over the state, Ragan Martin said.

Graduation Alliance, she said, was able to “ locate a lot of those kids who either had moved to another state or were doing something different. Maybe they were doing some sort of homeschooling or some sort of online schooling and just weren’t registered with the state.”

It’s the pandemic, silly

Some observers say the rise in unaccounted-for students represent societal changes brought on by the pandemic, which forced people into long bouts of isolation and worsened fears of ongoing chaos and violence such as school shootings.

It also highlights the lack of resources besetting school districts these days.

“The fact [that] we are now two years out [from COVID and] you’re still concerned about these children, once again, highlights the fact that the pandemic exacerbated the lack of resources in our systems,” Lisa Morgan, president of the Georgia Association of Educators, told State Affairs. “Our school counselors and school social workers would be those people working to identify those children who have not returned. And, frankly, we do not have enough counselors and social workers to do that.”

School districts also are focused on trying to return to normalcy now that the pandemic has subsided, some experts say. Teachers are dealing with a new school year and the students sitting in front of them, not the missing ones.

“They have their hands full with the kids who are showing up,” Leslie Hazle Bussey, CEO and executive director of the Georgia Leadership Institute for School Improvement, told State Affairs. “Teachers’ classrooms are full. No teacher is going to be like, ‘Oh, what about the kids who are not here?’ because they’re focused on the kids who are here.”

State school board member Martha Zoller takes a more pragmatic view.

“A lot of people moved during COVID to other places, and that’s something I don’t think we have a full accounting of yet,” Zoller said. “There are a lot of issues in public education, but I think we’re doing a pretty good job of getting people back to school.”

The Fiscal Cliff

The reality is likely to become more foreboding.

Districts that have lost a lot of enrollment and relied on federal pandemic relief money also are now about to lose their financial support from the federal government, Dee said.

Georgia received billions of dollars in ESSER money. That pandemic aid pipeline ends this year

“So there’s quite a bit of concern nationally that many school districts that have lost enrollment, that have been propping up their budgets with federal pandemic resources are going to see those resources expire soon,” Dee said. “They’re going to hit the so-called fiscal cliff and there’s concern there might be pressure on some of these districts to close under-enrolled schools and perhaps layoff staff.”

But for now, the search continues.

“Clearly the dropout population went up, during and immediately after the pandemic,” Harp said. “What we don’t know is, are all the students we’re saying weren’t found, are they all truly disengaged? The answer’s no. People move around, went to different states and the data is not telling the whole story. The whole story, I think, is going to take years to unwind.”

K-12 public, private & homeschool enrollment in Georgia

(Data are fall enrollment numbers)

Public Schools

2019: 1.71 million

2020: 1.69 million

Change: down 1.49%

Private Schools

2019: 98,638

2020: 100,246

Change: up 1.63%

Home Schools

2019: 77,993

2020: 91,142

Change: up 16.86%

Source: Stanford University economist and education professor Thomas S. Dee’s calculation based on the Common Core of Data and state departments of education.

Read more on education in georgia

Have questions, comments or tips? Contact Tammy Joyner on Twitter @lvjoyner or at [email protected].Twitter @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

Bruce Thompson, transformative Georgia labor commissioner and former state senator, dies at 59

ATLANTA, Nov. 25, 2024 — Bruce Thompson, Georgia’s labor commissioner and a dedicated public servant known for his transformative leadership and open-door policy, passed away yesterday after a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 59. Thompson, a former Republican state senator and military veteran, was elected labor commissioner in 2022. He took office in January …

Newly minted Senate Minority Leader Harold Jones II: ‘I’m not the typical back-slapping politician’

Nearly 10 years into legislative life, Sen. Harold Jones II wouldn’t change anything about the experience. “I love every minute of it. Even when I hate it, I love it,” the 55-year-old Augusta Democrat told State Affairs. Come January, Jones will add another role to his legislative duties: Senate minority leader, a job held for …

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …