Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo

Cooper-Carver Elementary School in Dawson, Georgia. (Credit: Cooper-Carver Elementary School)

- Program for thousands of struggling students caves in three years.

- Tension built between program leader and state schools chief.

- Audit targets consultant fees and spotty oversight.

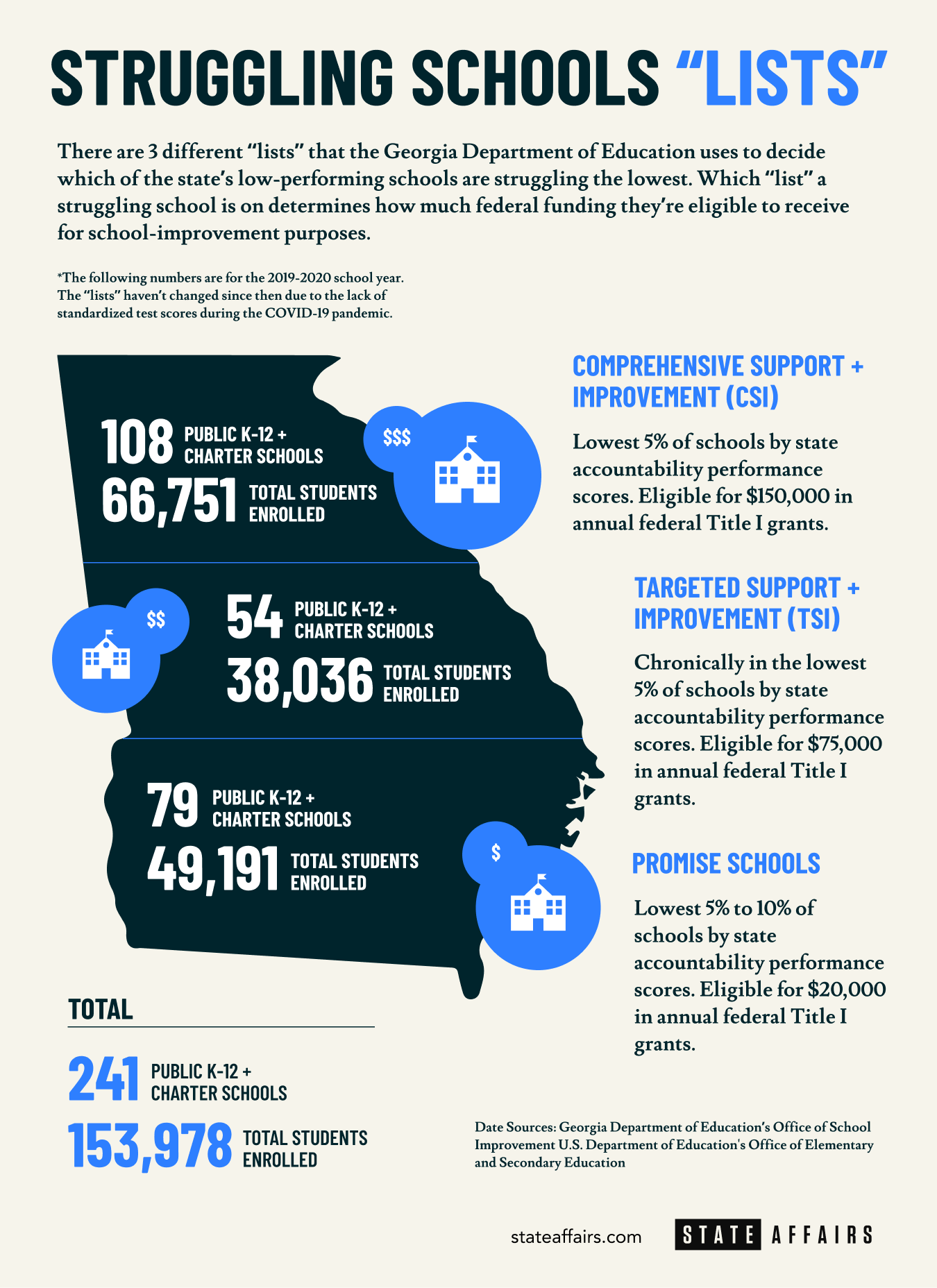

Under federal rules, each year, state officials in Georgia and across the U.S. must identify schools that rank among the lowest 5% in terms of standardized test scores, graduation rates and overall school-climate factors such as discipline issues and student-wellness programs.

Georgia, like other states, has established measures and metrics to identify those schools, which historically tend to represent primarily low-income, minority and rural communities where educational hurdles stem from overarching social and economic challenges.

In Georgia, 162 schools in urban areas like metro Atlanta, Macon and Savannah, and several rural areas, fell under the lowest 5% category for the 2019-20 school year — before the COVID-19 pandemic scrambled test scores and student performance. Another 79 schools teetered close to that 5% edge. Nearly two dozen of those schools came under the umbrella of the Chief Turnaround Office, qualifying those local teachers and administrators to work one-on-one with program specialists to analyze performance data, create improvement plans and complete leadership training.

By several accounts, the turnaround program saw gains in some districts like the Terrell County School System, where Cooper-Carver Elementary School in rural Dawson had languished in the test-score danger zone since 2015.

Like similar schools, Cooper-Carver struggled with realizing grade-level academic achievement across multiple subjects, especially in reading comprehension and math, and particularly among minority and economically disadvantaged students and students with disabilities. By 2019, the Chief Turnaround Office’s specialist assigned to Cooper-Carver helped school officials dig into performance data, improve lesson plans, train teachers and overhaul certain weak staff, according to reports provided by the school.

With that assistance, Cooper-Carver’s year-end collective Georgia Milestone test scores climbed from 47 to 69 points between the 2018-19 and 2019-20 school years, said the school’s principal, LaTosha Peters. The specialist also helped arrange mental health services and vision, dental and asthmas screenings, she said.

“They did a great job,” Peters said in a recent interview. “We got off the (struggling schools) list in a year and a half when it was expected to have taken years.”

Overall, more than half of the 21 schools under the turnaround program, including Cooper-Carver, saw federally required performance scores improve between the fall of 2018 and the spring of 2019, according to state data. Several schools saw no issue with the non-Georgia career of Thomas, who was born and raised in Savannah. Local administrators gave high marks on their partnerships with the program and its specialists during the 2018-19 school year, according to surveys reviewed by State Affairs.

“We had so many programs, interventions, curriculum pieces and the like (before the turnaround program), but none of it caused a rise in student achievement,” Tangela Madge, the superintendent of Randolph County School System, said in a 2019 letter to state lawmakers.

“Through effective and succinct 90-day planning, (Thomas) and his team of transformation specialists have helped our middle school experience double-digit gains.”

Debbie Alexander, a veteran educator from Augusta who led the turnaround program’s specialist teams in 2018, also thought the program got off to a good start. But she, like Peters, soon began hearing rumbles from other districts who felt less satisfied with the turnaround work.

“For me, it was really a wonderful experience,” said Alexander, who is now the executive director of the Central Savannah River Area Regional Educational Service Agency. “But (the turnaround program) was short-lived, in my opinion. It had just really begun.”

NEXT

Header image: Cooper-Carver Elementary School in Dawson, Georgia. (Credit: Cooper-Carver Elementary School)

Gov. Kemp calls on state agencies to be fiscally restrained amid record $16.5B surplus

The Gist Gov. Brian Kemp asked the state’s 51 government agencies for continued fiscal restraint when drafting their amended fiscal year 2025 and 2026 budgets. Most agencies adhered to his request even as the state’s general fund surplus hit a record $16.5 billion last month. Forty-five agencies, excluding state courts, followed the governor’s instructions to …

Georgia defies bomb threats as election chief declares a “free, fair and fast” vote amid record turnout

ATLANTA – Despite dealing with over 60 bomb threats, Georgia’s election chief said Tuesday the state’s general election went smoothly. Georgia had a record turnout with nearly 5.3 million people voting, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told reporters. Election officials in the state’s 159 counties have until 5 p.m. to certify votes. “We had a …

In the (state)house: Meet the newest members of the Georgia legislature

When lawmakers reconvene at the state Capitol on Jan. 13, there’ll be a cadre of new faces in the 236-member Georgia General Assembly, one of the nation’s largest state legislatures. All 236 statehouse seats were up for election this year. Most candidates ran unopposed. Incumbents in contested races easily kept their seats, with the exception …

2 young Democrats win Statehouse seats as Republicans hold majority

ATLANTA — Many Statehouse incumbents appeared to beat back challengers Tuesday, ensuring their return to the Capitol in January. Republicans retain control of the House and Senate. Two Generation Z candidates will join the 236-member Legislature as new members of the House of Representatives: Democrats Bryce Berry and Gabriel Sanchez. Berry, a 22-year-old Atlanta middle …