Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo

School money illustration (Credit: iStock)

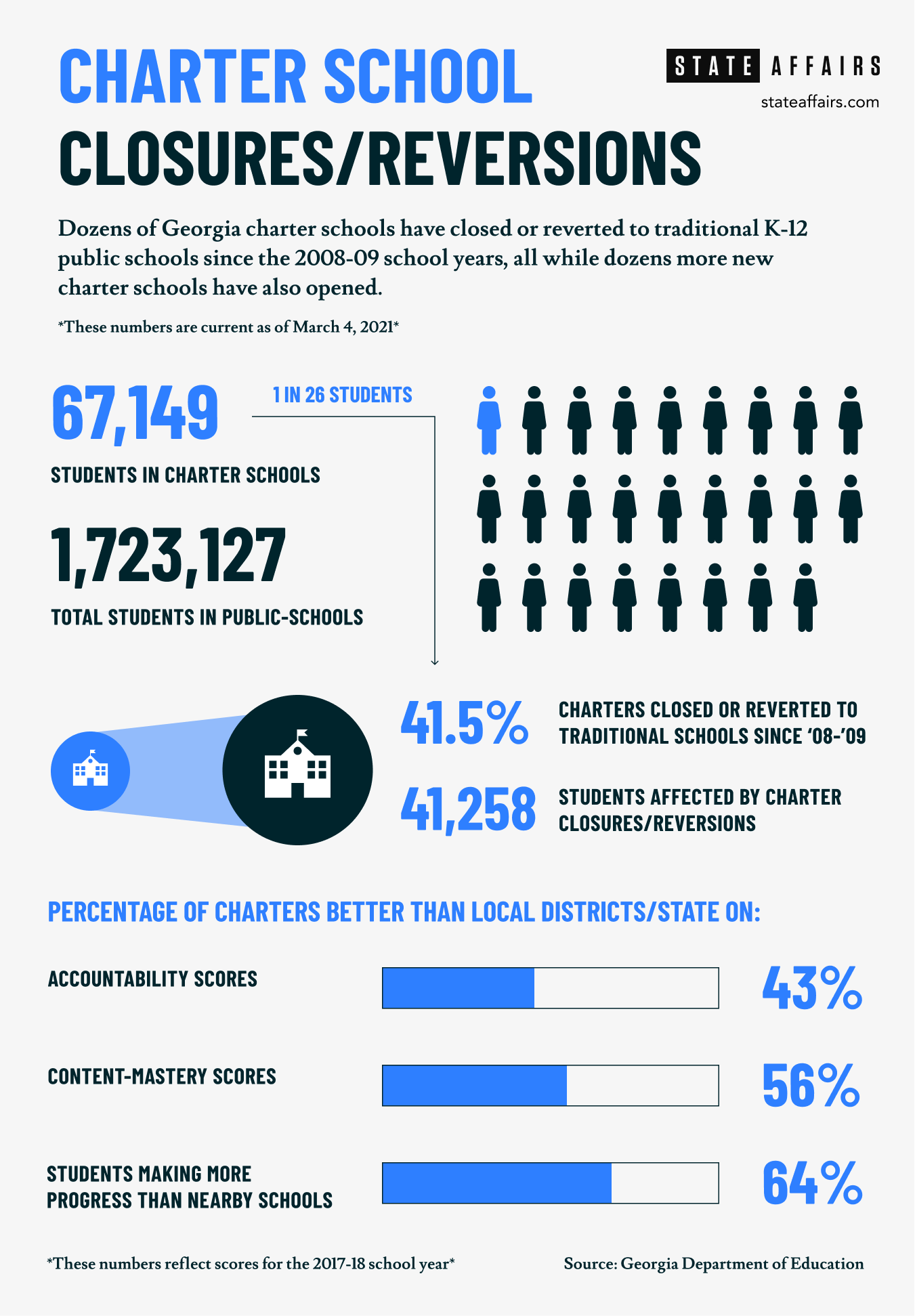

- Roughly 1 in 26 Georgia students enrolled in charter schools in spring 2021.

- Less money spent per student in local charter schools than nearby schools.

- Limited funds to open new state charter schools.

Georgia’s state-funded charter schools are free and open to all students, but many miss out on local tax dollars that benefit students in traditional K-12 public schools.

More than 67,000 students enrolled in charter schools in the spring of 2021, totaling roughly 1 in 26 students out of the state’s total 1.7 million student population, according to state data. Most charter schools have less money to spend per student than traditional schools in their surrounding districts or compared to the state average, state Department of Education data shows.

Charter advocates say funding disparities make it tough for many charter schools to boost student academic progress compared to nearby schools, which is a vital part of the agreements that allow them to exist.

There are many kinds of charter schools in Georgia, each operating based on their agreements with state or local school districts.

Charter schools face tighter academic scrutiny in return for relaxed rules on what courses to teach, student schedules and teacher qualifications. They can also set up independent governing boards or advisory councils, unlike traditional public schools that take orders from local officials who oversee all schools in a given district.

Like traditional public schools, charter schools in Georgia receive state funding based on how many students they enroll each year. They can also qualify for certain federal grants in special education and for school improvement.

Charters and traditional public schools differ when it comes to how much each gets in revenues from local taxes. State law gives traditional K-12 schools a share of local property and education-earmarked taxes. Charter schools are not legally entitled to receive local tax dollars, leaving it up to district officials whether to share their local taxes or not.

Charter-school advocates estimate most charter schools on average have access to 25% less funding than traditional public schools in Georgia.

More than half of the roughly 50 charter schools that have agreements with local districts saw less spending on each student than other schools in their same districts in 2019, according to state data.

Even fewer locally run charter schools matched the student spending of nearby schools in 2018 and 2017. Less than one-third of charters spent more per student than their districtwide averages in 2018, while roughly one-fourth did so in 2017, state data shows.

That disparity holds true for charter schools in Atlanta Public Schools, which as a district has one of the highest per-student spending averages in the state. In 2019, 11 out of Atlanta’s 18 charter schools spent less per student than the district average.

Another batch of charter schools that contract directly with the state also saw less per-student spending during those years than the state average – even as the number of charters under state oversight grew from 24 in 2017 to 32 in 2019. Each of those years saw less than 25% of state-run charter schools match or exceed the state average for how much schools spent on each student, according to state data.

Those funding shortfalls came as state lawmakers moved in 2018 to hike charter schools’ share of state funds to offset the lack of local tax dollars. Legislation signed into law that year set up charter schools to receive an extra roughly $42 million in 2019 and $46 million in 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic prompted officials to slash school spending across Georgia.

Charter-school advocates view money spats between some schools and their local districts as a major reason for a slowdown in the number of new charter schools opening in recent years.

Scuffles have even broken out between some charter schools and local districts over the tax dollars. Seven charter schools in DeKalb County even sued their local district over funding issues in 2020.

Tony Roberts, the president and CEO of the nonprofit Georgia Charter School Association, said he’s worried that local districts may ramp up efforts to take away funding and services like buses from their charter schools to bolster budgets for traditional public schools.

“It really is a way of putting a squeeze on the charter schools,” Roberts said in a recent interview. “That way it’s off your budget and it’s hunky-dory then.”

As a result, he and other advocates anticipate more charter schools to open under state oversight through Georgia’s State Charter Schools Commission. That agency has the authority to approve petitions for new state charter schools or shut schools down for poor performance.

Like other state agencies, the charter-school commission has a tight budget that limits its ability to open new schools or allow locally-run charters to switch over to state oversight, according to state officials. The commission has approved state charters for many new schools over the last few years while also turning down petitions for several other hopefuls. Georgia has around $27 million this year to divvy up for authorizing charter schools and systems across the state, according to budget figures.

Money constraints are only part of the equation for opening new charter schools, said the commission’s chair, Buzz Brockway. New schools also have to show proof they can stand the test of time and not be closed due to financial issues or low academic performance, he said.

“There’s a finite amount of time and we don’t want to experiment because a couple years of lousy education in a child’s life is devastating,” said Brockway, a former state lawmaker from Gwinnett County.

“We can’t just hand these charters to everybody," he added. "I’d much rather be accused of being tight-fisted than opening up a lot of schools that don’t do a good job.”

What else would you like to know about Georgia's public schools? Share your thoughts/tips by emailing [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header image credit: iStock

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

House speaker Jon Burns hires new communications director

House speaker Jon Burns, R-Newington, announced today that he has hired a new communications director. Kayla Roberson, who has served as press secretary at the Georgia Chamber for the past year or so, will now oversee all external communications, media relations and strategic messaging for Burns.

“I’m excited to welcome Kayla to our team,” Burns said in a statement. “Kayla has an excellent background, deep skill set and strong work ethic, and we’re excited to have her on board to continue getting our message out and sharing the House’s priorities ahead of and into the next session.”

A double major in political science and journalism at the University of Georgia, where she graduated in 2022, Roberson interned for U.S. Rep. Andrew Clyde, a Republican in north Georgia’s 9th Congressional District, and worked as a consultant for GOP political candidates before joining the Georgia Chamber.

“I’m beyond grateful for the opportunity to work under the leadership of speaker Burns,” Roberson told State Affairs. “Whether it’s improving education opportunities, putting money back in the pockets of hardworking Georgians, creating jobs or supporting our rural communities, speaker Burns always prioritizes doing what is best, and what is right, for Georgia.”

Political strategist Stephen Lawson, who has held the top communications role for the speaker since last December, announced he’s joining Dentons, where starting today he’ll lead the global law firm’s public affairs efforts.

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Global bird flu disrupts Georgia exports, costing chicken producers millions

ATLANTA — A global bird flu that has rapidly spread from birds to dairy cows, milk supplies and humans has cost untold millions of dollars in lost export business in Georgia, the nation’s leading poultry producer, officials with the state Department of Agriculture and poultry industry said.

Georgia has had only three reported cases of H5N1 avian influenza since it reemerged in 2022. The last of those cases was resolved in November 2023 but ramifications of those outbreaks continue to have a big effect on the state’s ability to export chicken and chicken parts, such as chicken feet, to different countries, including China, one of Georgia’s biggest export markets for chicken feet.

In 2022, frozen chicken feet, for example, accounted for more than 85% of all U.S. poultry exported to China, according to Farm Progress, publisher of 22 farming and ranching magazines.

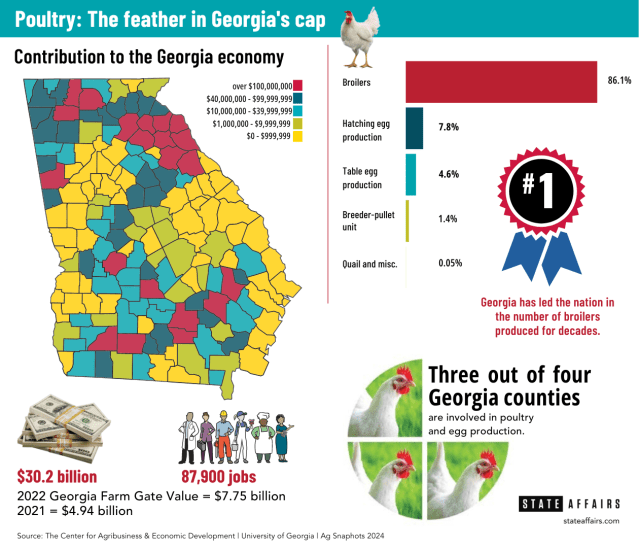

The $30 billion poultry industry is Georgia’s largest segment in its No. 1 industry — agriculture.

China has also placed a ban on the import of chicken products from 41 other American states. The ban on Georgia products went into effect Nov. 21, 2023. Efforts to reach the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C. were unsuccessful.

Georgia Poultry Federation President Mike Giles estimates the state’s loss at “well into the millions of dollars.”

“It’s a significant amount in a significant export market for us,” he said. “Poultry paws [feet] immediately lose value because of the loss of demand.”

The ban has forced Georgia poultry producers to find alternative markets for their products that would normally be headed to China.

“Some are sold domestically, some are frozen and stored, hopefully to find markets later on, and some go to other countries,” Giles said.

This isn’t the first time China has banned U.S.-produced poultry products due to a bird flu outbreak. The country instituted a ban in January 2015 which lasted until November 2019 — even though U.S. poultry products were deemed free of the disease by August 2017.

After that ban was lifted, China’s appetite for American-produced chicken products became voracious.

In 2022, U.S. producers shipped nearly $6 billion in poultry meat and related products (excluding eggs) to over 130 countries. China has emerged as the second largest destination for U.S. poultry exports, increasing from $10 million in 2019 to a record $1.1 billion in 2022, according to Southern Ag Today.

Chicken paws, for instance, are eaten in many Asian countries, including the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia and Korea.They can also be found on Chinese dim sum menus throughout the U.S. and are also popular in Jamaica, Trinidad, Russia and Ukraine in everything from soups and curries to fried snacks.

Three Georgia counties have reported H5N1 outbreaks since 2022. The most recent case was late last year. Henry, Sumter and Toombs counties each reported one case of H5N1 bird flu. Those outbreaks are resolved, poultry and state agriculture officials say.

“When HPAI cases are found in any state, that state is given a designation that could lead to foreign countries halting trade on poultry products from that state,” Georgia Department of Agriculture spokesman Matthew Agvent told State Affairs.

Not since 2016 has the United States experienced such a fast-moving case of the H5N1 avian influenza. In the last two months, the virus has spread in parts of the United States from birds to dairy cows, some milk supplies and humans. Two people — a Texas dairy worker and a prison inmate in Colorado who was killing infected birds at a poultry farm — are reported to have caught the virus, according to news reports. The outbreak is the largest in recent history, impacting both domestic poultry and livestock as well as wild birds and some mammal species.

State officials are continuing to monitor the national outbreak and its impact on Georgia.

Georgia’s poultry & egg industry: At A Glance

Annual economic impact: $30.2 billion

Percentage of the Agriculture industry: 58% *

Jobs: 87,900

Counties involved in poultry & egg production: 3 out of 4

National ranking in chicken broiler production: No. 1

Daily production of table eggs: 7.8 million

Daily production of hatching eggs: 6.5 million

Pounds of chicken produced daily: 30.2 million

Pounds of chicken produced annually: 8 billion

Number of chicken broilers processed each day: 5 million

Counties involved in poultry & egg production: 3 out of 4

Source: Georgia Poultry Federation; The Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development, University of Georgia, Ag Snapshots 2024; Georgia Poultry Federation.

Have questions? Contact Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs and drink milk? Answers to your most pressing questions about the latest bird flu outbreak

A two-year-old strain of bird flu has heightened concerns in Georgia and the rest of the country after the virus recently spread to dairy cows. Here’s what you need to know about the virus and its impact on Georgia and the rest of the country. What are the symptoms of this flu in humans? Eye …

Kemp signs bills on education, health care, taxes

Gov. Brian Kemp signed a slew of bills over the past week or so, including the private school voucher bill long sought by Republicans and a bill that will ease regulations over the construction and expansion of medical facilities in rural areas.

His bill-signing events were clustered into themes: education, health care, military members, human trafficking and Georgia’s coastal communities.

Education

Among the education-related bills Kemp signed was Senate Bill 233, also known as the Georgia Promise Scholarship Act, which provides the families of Georgia students enrolled in underperforming school districts with $6,500 scholarships that can be used toward private school or homeschooling expenses, including tuition, fees, textbooks and tutoring.

“Georgia is affording greater choice to families as to how and where they receive their education, while also continuing our efforts to strengthen public schools, support teachers, and secure our classrooms,” Kemp said, and thanked leadership in the House and Senate for prioritizing passage of the bill, which had failed in a close vote in 2023.

Democrats and many public education advocates who opposed the bill argued it will drain resources from public schools and primarily benefit students from wealthy families.

Kemp also signed Senate Bill 351, sponsored by nine Republican senators, which will require social media companies, as of July 1, 2025, to verify their users are at least 16 years old unless they receive approval from a parent.

House Bill 409, sponsored by Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, directs school systems to consider not having bus stops where a student would have to cross a roadway with a speed limit of 40 mph or greater. The bill also increases the penalty for passing a stopped school bus to $1,000 from $250.

Kemp noted that Ashley Pierce, the mother of Addy Pierce, an 8-year-old who was fatally struck by a motorist as she boarded her school bus, “passionately advocated for and was instrumental in the passage of this legislation.”

Senate Bill 395, sponsored by Sen. Clint Dixon, R-Gwinnett, states that no school visitor or personnel can be prohibited from possessing an opioid reversal drug such as Narcan and directs schools to maintain a supply. It also allows opioid antagonists to be sold in vending machines and directs certain government buildings to maintain a supply of at least three doses.

Senate Bill 464, also sponsored by Dixon, creates the School Supplies for Teachers Program to financially and technically support teachers purchasing school supplies online. It also creates an executive committee of five voting members within the Georgia Council on Literacy and limits the number of approved literacy screeners to five, one of whom must be available to schools for free.

Health care

The governor chose his hometown of Athens as the venue to sign several bills aimed at improving health care in rural and underserved communities.

Among them was House Bill 1339, sponsored by Rep. Butch Parrish, R-Swainsboro, which revises the Certificate of Need process by which the state determines if and how new medical facilities can be built or expanded. The bill provides for several new exemptions, including psychiatric or substance abuse inpatient programs, basic perinatal services in rural counties, birthing centers and new general acute hospitals in rural counties. It also raises the total limit on tax credits for donations to rural hospital organizations to $100 million from $75 million.

Senate Bill 480, sponsored by Sen. Mike Hodges, R-Brunswick, establishes student loan repayments for mental health and substance use professionals serving underserved youth in the state or in unserved geographic areas disproportionately impacted by social determinants of health.

House Bill 872, sponsored by Rep. Lee Hawkins, R-Gainesville, chair of the House Health and Human Services Committee, expands cancelable loans for certain health care professionals to dental students who agree to practice in rural areas.

Senate Bill 293, sponsored by Sen. Ben Watson, R-Savannah, chair of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, reorganizes county boards of public health and opens the qualifications for the CEO of each county board of health to include either licensed physicians or people with a master’s degree in public health or a related field.

Military members and veterans

Kemp on Wednesday focused on bills to improve military recruitment and provide more work opportunities for veterans and military family members.

House Bill 880, sponsored by Rep. Bethany Ballard, R-Warner Robins, allows spouses of military service members to work under a license they hold in good standing in another state while under the supervision of an existing Georgia medical facility or provider.

Senate Bill 449, sponsored by Sen. Larry Walker, allows military medical personnel to practice for 12 months while a license application is pending, including working as a certified nursing aide, certified emergency medical technician, paramedic or licensed practical nurse. The bill also creates a new advanced practice registered nurse license and makes it a misdemeanor to practice advanced nursing without a license.

Human trafficking

The governor on Wednesday was accompanied by first lady Marty Kemp and other members of the GRACE Commission for the signing of an anti-human trafficking package. It includes Senate Bill 370, which adds certain businesses to the list of organizations that must post human trafficking notices, including convenience stores, body art studios, businesses that employ licensed massage therapists and manufacturing facilities.

Sponsored by Sen. Mike Hodges, R-Brunswick, the bill also allows the Georgia Board of Massage Therapy to initiate inspections of massage therapy businesses and educational programs without notice and requires massage therapy board members to complete yearly human trafficking awareness training.

House Bill 993, sponsored by Rep. Alan Powell, R-Hartwell, creates the felony offense of grooming of a minor and creates new penalties for offenses relating to visual mediums depicting minors engaged in sexually explicit conduct.

House Bill 1201, sponsored by Rep. Houston Gaines, R-Athens, allows human trafficking survivors who received first offender or conditional discharge status to vacate that status for certain crimes, as long as the crime was a direct result of being a victim of human trafficking.

Coastal communities

Earlier today in Brunswick, Kemp signed legislation impacting Georgia coastal communities, including House Bill 244, which amends the laws around how wild game can be hunted and how seafood dealers operate, and House Bill 1341, which designates white shrimp as the state’s official crustacean.

Taxes

Earlier this month Kemp signed several bills related to taxation, including House Bill 1015, sponsored by Rep. Lauren McDonald, R-Cumming, which lowers the state income tax for tax year 2024 to 5.39%, accelerating a multiyear drop in state income taxes that started at 5.75% in 2023 and will continue through 2029.

The Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget estimates the tax cut acceleration will save Georgia taxpayers approximately $1.1 billion in calendar year 2024 and about $3 billion over the next 10 years.

Kemp also signed House Bill 1021, sponsored by Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, which increases the state’s income tax dependent exemption to $4,000 from $3,000.

House Bill 581, sponsored by Reps. Shaw Blackmon, R-Bonaire, and Clint Crowe, R-Jackson, enables a constitutional amendment (House Resolution 1022) to let voters decide whether counties can provide a statewide homestead valuation freeze, which limits the increase in property values to the inflation rate.

The governor has until May 7 to sign or veto bills passed during the legislative session that ended on March 28. Those he takes no action on will automatically become law.

Legislation signed by Kemp is posted on the governor’s website.

Read these related stories:

Have questions, comments or tips on education in Georgia? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS