Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

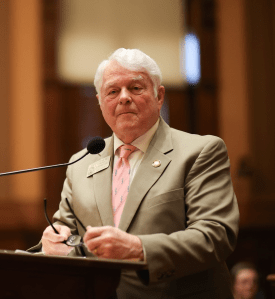

Request a DemoKevin Tanner talks improving mental health access in Georgia

Commissioner Kevin Tanner is sworn in by Gov. Kemp on December 21, 2022. (Office of Gov. Brian P. Kemp)

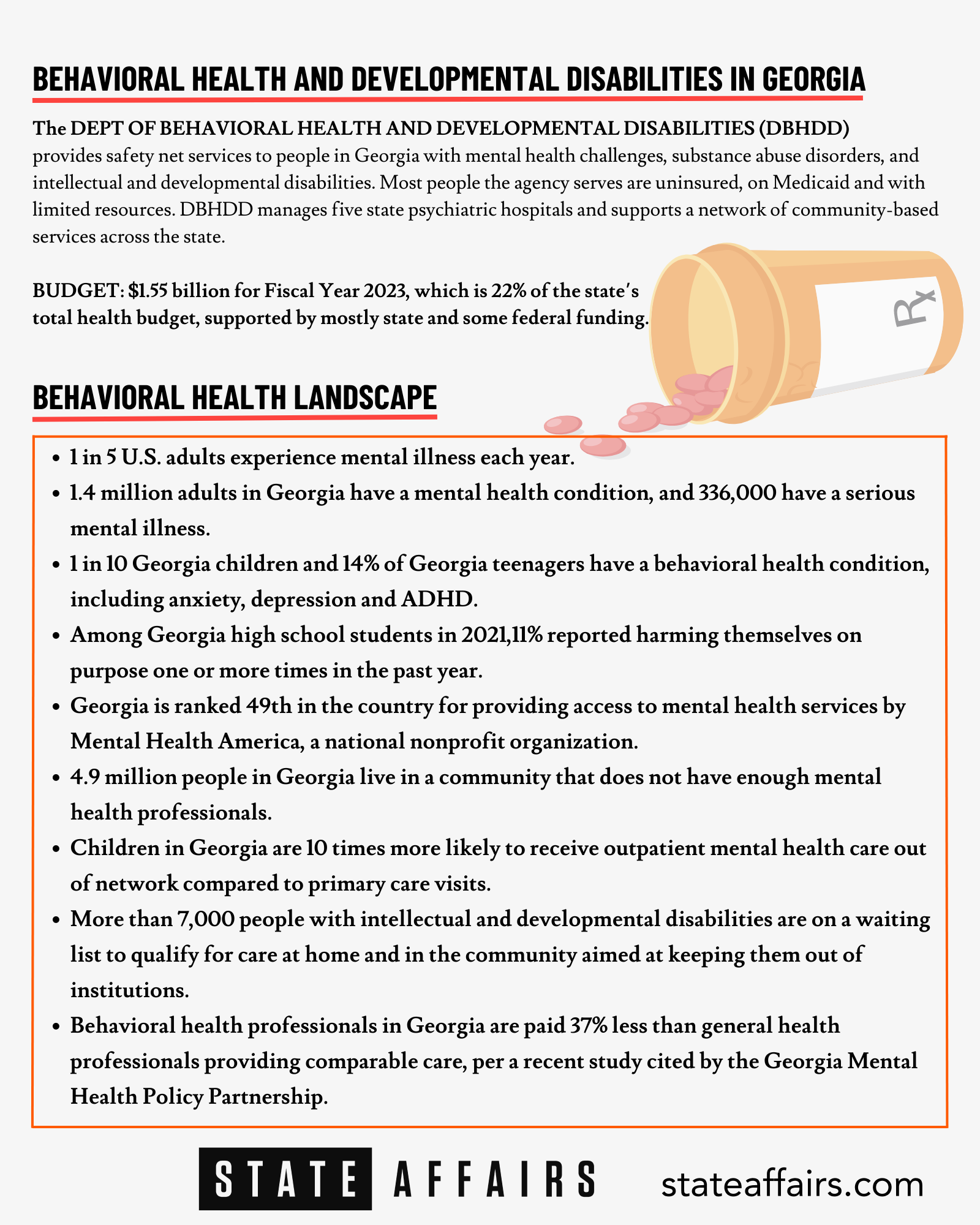

Kevin Tanner took over as commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD) last month, with a challenging mandate to oversee an agency responsible for meeting the health needs of some of the state’s most vulnerable people, including those undergoing mental health crises and battling substance abuse issues.

A former police chief, county manager and four-time Republican state legislator, Tanner has been at the forefront of efforts over the past several years to change Georgia’s status as one the bottom-ranked states in the country for access to mental health care. With the passage of the sweeping Mental Health Parity Act in Georgia last year, Tanner has an opportunity to leverage the momentum in state government to make ambitious improvements to the state’s behavioral health system.

State Affairs spoke to Tanner, who received his undergraduate degree from University of North Georgia College and a master in public administration from Columbus State University in Columbus, about how he hopes to implement key reforms and about his priorities for this year. The conversation is edited for clarity, brevity and length.

Q. Tell me a little about your background and what brought you to this work?

A. Well, I guess in March, it will be 33 years since I started in some type of public service. I actually started my service career in law enforcement and worked for a good long time in a lot of different capacities, including running a law enforcement agency [in Dawson County]. And one of the things even back then that I became frustrated with on a regular basis was going on calls dealing with people who were suffering from behavioral health, mental health issues, and oftentimes not really having a good answer for the family that was there crying out. And you know, most folks when they have a need they call 911. And the police are supposed to solve all their problems, but so many times we just didn't have a good answer.

[After college] I worked my way into county management, became a county manager and did that for a number of years. And enjoyed that. And then I had always been involved in some way [with] politics, not directly involved but had helped other people run for office and had been involved in the political party at the local and state level. Long story short, I ended up running, getting elected and I spent four terms in the General Assembly [as District 9 representative].

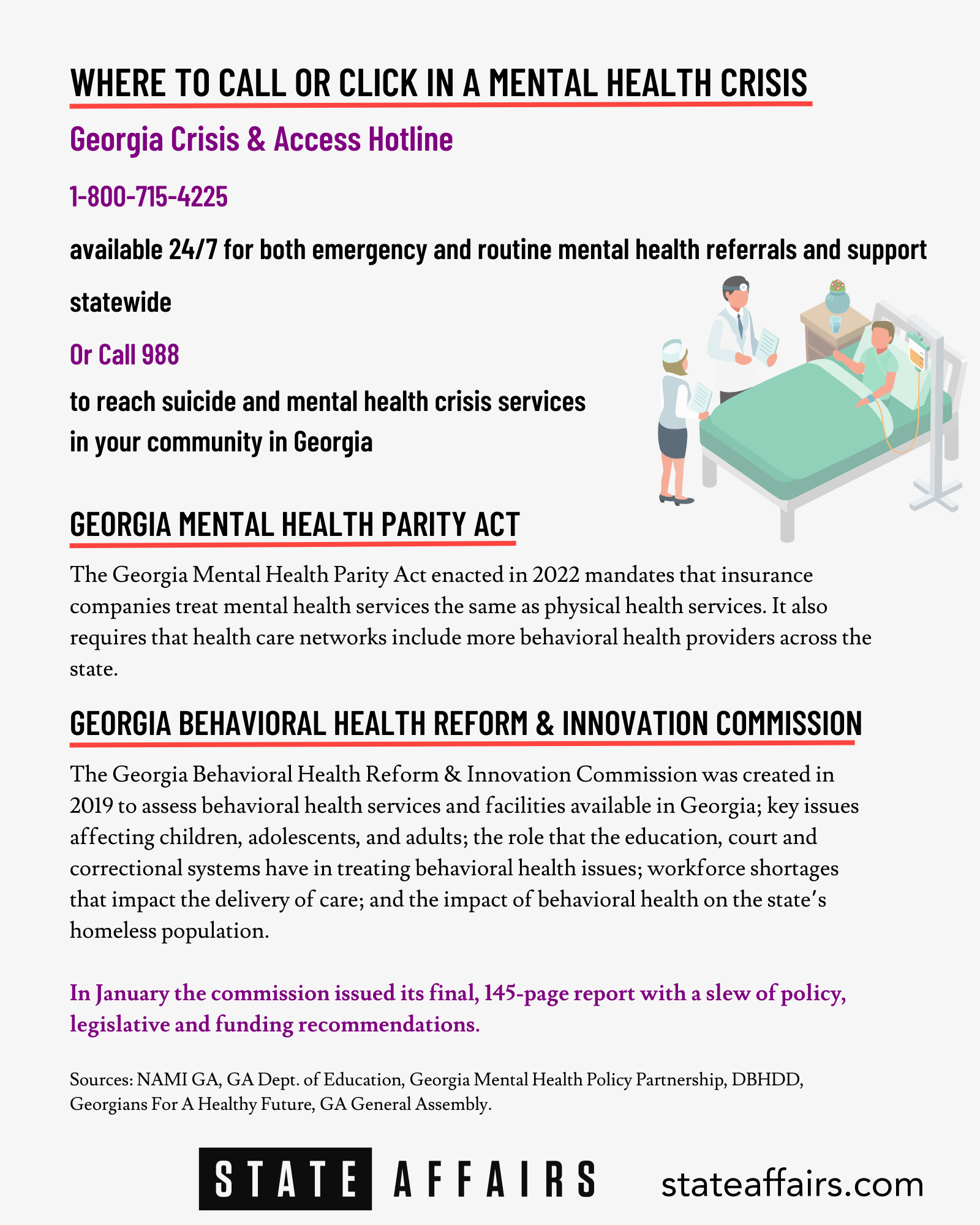

All the way back in 2013, I introduced legislation to create a study committee on mental health and didn't have a lot of success, really, with that at the time. But as I developed my relationships in the General Assembly, in 2019 I revisited the issue. I’d heard several stories, but one in particular, where a gentleman I was renting a house to was in mental health court and things didn't go well for him. And I just wanted to try to see if I could help make some positive changes to the system. So from there, I worked with Speaker David Ralston and in 2019, created and ultimately the governor signed and became codified into law, the Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission [BHRIC]. So later that year, Governor Kemp named me the chair and I've been chairing that for the last three years. And our work resulted in speaker Ralston's House Bill 1013 [Georgia Mental Health Parity Act], which passed last session. So I’m very proud of that. We just released the newest [Behavioral Health Commission] report for 2022.

Q. How can you leverage your position to accomplish some of the things that you've advocated for in the past, particularly in some of the areas where progress has been lacking?

A. Well, let me say this, I was not looking to be the commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. It's not anything I had ever even thought about quite honestly. I was county manager in Forsyth County, I had 2,000 employees, I had a great operation. And I'd surrounded myself with some very bright people, and my job was fairly easy because I had built a great team of people and was running one of largest counties in the state and life was fairly good. When the governor approached me about this opportunity, I had to spend a little bit of time thinking about it.

But it came down to the fact that so much of my life had been working toward understanding problems within the system, maybe some shortfalls, but also looking for solutions because … I don't like to just stand on the sidelines and complain about things. And a lot of people like to point out what somebody else is doing wrong. That's really not my personality. I want to be in the middle of trying to help find the solution. So I think what I hope to be able to bring to this position is I have, I think, a skill set. I know I don't have all the answers. And I know I'm not the expert on all things mental health, or developmental disabilities. But just like we did with the Behavioral Health Commission, I know how important it is to bring the right people to the table, to get the right opinions, so that we can listen to those experts. And then from that formulate a process and a pathway to success.

Q. One of the key elements of making the Mental Health Parity initiatives work is to expand and retain the mental health workforce in Georgia. What specifically are you focusing on this year to make that possible?

A. Yeah, that's a very astute observation. Because I will tell you since I've been here in almost every meeting we’re in, whatever problem we're talking about, the solution always goes back to the same thing, and that's workforce. So many of the challenges we're facing right now, of building out the crisis model that we need to be successful in Georgia, the barrier is workforce. And we've recognized that at Behavioral Health Reform Commission level … and we put some things in place and legislation around loan forgiveness [for people pursuing mental health education and training] and some other things. That is a step. But it's definitely not going to fix the problem. And I think all of us have recognized there's not a silver bullet to this issue.

But one of the things that Representative Mary Margaret Oliver [D-Decatur] and Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, who chairs the access subcommittee, one of the things they both jointly have talked about this past year, and it's in the report, is the fact that reimbursements are so low in Georgia. There has not been a behavioral health provider reimbursement increase in I think it's 17 years in Georgia. Our developmental disability provider rates are very low. The department has already released the results of that study and we’re taking public comments on the developmental disability piece of that now.

And that should result in a significant increase in providers. DCH [Department of Community Health] was directed under House Bill 1013 to do the same thing for Medicaid providers for behavioral health. They've gotten their initial results back and they've not released that yet. But I can tell you it will be a significant increase if we're able to implement that.

Q. Now, what's the funding source and mechanism for that? What will make that happen?

A. Well, the way it would work, for instance, the one we're doing public comment on now is, two-thirds of it would be paid for by the federal government and one-third would be state dollars. So it would require the state to commit money in the budget. And then in turn, once that happens, we send that up to the federal government, and they would ultimately approve it. Because obviously, we had to hire a reputable, recognized company [Accenture] that deals with this on a daily basis all across the country. And they've done a very independent professional study that the federal government would adopt. So really the biggest thing would be the General Assembly and appropriators have to appropriate funds.

Q. And what are you requesting as the budget allocation for the workforce increase?

A. We actually have not finalized those numbers. Because we know that on average it would increase the provider payments significantly. But there's so many factors involved in it that we’re waiting on, we're getting some data from DCH, and some other agencies. And then from that, we're going to be able to run those numbers. We hope to have that within the next 45 days.

Q. And do you have a top-line total budget recommendation for the amended budget for this year for your department?

A. Well, the direction received from the governor's office was it is a flat-line budget, so no increases.

Q. There is a big surplus that a number of agencies are looking at, in hopes of increasing budgets.

A. Yes. And obviously we'll be having conversations with the governor's office and others about the needs of the department. One of the things I also think is important that the department needs to do is to lay out a clear plan. We’re getting ready to undertake a bed study because as we build out our crisis network, we need to know so that I can tell the governor's office and the appropriators that five years from now, I'm going to need this many beds — here's where I need those beds, and here's what type of bed I need.

Q. The Mental Health Parity bill is a landmark set of directives on paper but as you say, it must be implemented and it must be funded. What are the key areas that need to be funded at a higher level this year or in following years than they have been in the past for the bill to work as intended?

A. Well, I think it's important, if you look back at Georgia, back to 2010, when the settlement agreement with the Department of Justice was entered into, Georgia has really had to, in a pretty short period of time, create a community-based system of behavioral health. So it's a young system of delivery of services. So we've come so far, but I think we have to build out that crisis system and that network. So right now we're reliant upon private beds to help offset our internal crisis system, and we've got to build that out, we obviously are going to need additional crisis beds across the state, we're going to need some additional other types of beds, for our developmental disability population, and we need additional providers, and additional bed space for home-based care.

There’s a capital investment. There’s an ongoing provider investment. But it also goes back to the reimbursements. Because it's very challenging for us as a department to get people to want to be a provider for us when our reimbursement rates have not been changed in so many years. So I always say it's what comes first, the chicken or the egg, you've got to fix the reimbursement rates, so we can get our workforce addressed in order to really build out this crisis system. But I say all of that, to answer your question, to continue to adequately build out the crisis network system in Georgia is the number one thing we have to be able to look at.

Q. And for our readers, can you define what the crisis network is?

A. Yeah, and let me back up and give you an example. You have someone who's reading your article, they themselves are in crisis, or a loved one is in crisis. And they pick up the phone and they call 988. And they access the Georgia Crisis System. They call our GCAL [Georgia Crisis & Action Line] center, and the person who answers the phone is a trained professional, to talk with them, to evaluate what their needs are. And then they can dispatch a crisis mobilization unit. So a trained professional will go out to that person, if that's the need. We're not talking about law enforcement, or an ambulance, we're talking about trained mental health professionals, they go out, provide an assessment, and help get that person into whatever level of care they need at the time. So that's one of the ways that people can come into the system.

And then we have partners and we have community service boards all across Georgia; I think we have 23 boards currently. And many of those run crisis stabilization units. And those units are typically short-term, three-to-seven-day placements of individuals who are in crisis. They can go there, they can receive care and treatment, get regulated on medication, et cetera. And then from there, they're discharged with a treatment plan that may involve follow-up with the right type of clinician with peer support and all the wraparound level of services they need to be successful. And our crisis process is coordinating all of that.

Then there's longer-term care with different types of beds that may be for 30 days. And then of course, we operate five state hospitals for people who need more significant longer-term care in our hospital settings. So that's the crisis network that we have in Georgia and DBHDD is responsible for that.

Q. Housing is such a big area that affects your ability to help people who are having a mental health crisis, including the homeless population. Can you speak to that?

A. Yeah, housing is an issue. And it's specifically an issue for transitional housing, when we have someone that maybe comes out of a crisis center or comes out of a hospital, being able to make sure that we have the right place for that person to go. Good, stable housing is important. We also have community-based housing availability, whether it be a group home or another type of facility. And, again, it's challenging to get those providers right now because of those reimbursement rates. So I sound like a broken record on that. But that's on purpose. Because so many of our problems come back to reimbursements. But long-term housing needs are also obviously an issue. You mentioned the homeless population. There's a pretty good percentage of our homeless population that suffer from behavioral health issues and being able to find ways to address that is important. And obviously, there's a balance because we have a crisis system, but we're not able to force someone to accept treatment and accept help. But all of those things you mentioned are real issues that we’ve got to find ways to solve.

Q. Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Michael Boggs, who serves on the Behavioral Reform Commission’s Courts and Corrections subcommittee, mentioned recently, that before we can do anything else for people in the criminal justice system with behavioral health needs who are reentering society, they need to have a place to live and food to eat, and oftentimes they don't.

A. Yeah, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, right? Food, shelter, safety. And I'll tell you that in Forsyth County, I was county manager there and one of the things they’re working on now, they have an RSAT [Residential Substance Abuse Treatment] program they run through the sheriff's office. We funded it and they also had grant funding for that there, but they're actually looking at meeting this week, with the city of Cumming, and trying to request some opioid funding for transitional housing to be built there in Forsyth. They've already identified a location to build that transitional housing, and part of it would be RSAT, for people who have substance abuse, addiction issues that need transitional housing. So there are examples of good things occurring there.

Q. So on a statewide level, how could that translate?

A. Well, we have to do something, right? We've talked a lot about these issues, but there has to be a stake put in the ground and we have to try something. And I think what's happening in Forsyth is going to be a good test model to see if this can work, how does it work? And if it works well, those things need to be duplicated. That’s one of the things that I pushed for, and we received ARPA [American Rescue Plan Act] funds in Forsyth. And we used almost all of those funds to design — and they're about to go out to bid on building a whole health facility. So it's going to be a 64,000-square-foot, $35 million complex. It’s going to be a health department and a mental health facility in one building, and the mental health side is going to have 30 crisis beds. And it's also going to have a 24-hour emergency room with a prescriber on duty 24 hours a day. So if someone's in crisis, they can go there instead of the local ER, but also it helps with the stigma, because then if they may be going to get their physical health or their mental health they can go into the same facility. So there's some pretty exciting things happening. And I think some of those things can be duplicated around the state.

Have questions, comments or tips about Georgia’s behavioral health system? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on Twitter @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Twitter @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @stateaffairsUS

Instagram@stateaffairsGA

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Kemp signs bills on education, health care, taxes

Gov. Brian Kemp signed a slew of bills over the past week or so, including the private school voucher bill long sought by Republicans and a bill that will ease regulations over the construction and expansion of medical facilities in rural areas.

His bill-signing events were clustered into themes: education, health care, military members, human trafficking and Georgia’s coastal communities.

Education

Among the education-related bills Kemp signed was Senate Bill 233, also known as the Georgia Promise Scholarship Act, which provides the families of Georgia students enrolled in underperforming school districts with $6,500 scholarships that can be used toward private school or homeschooling expenses, including tuition, fees, textbooks and tutoring.

“Georgia is affording greater choice to families as to how and where they receive their education, while also continuing our efforts to strengthen public schools, support teachers, and secure our classrooms,” Kemp said, and thanked leadership in the House and Senate for prioritizing passage of the bill, which had failed in a close vote in 2023.

Democrats and many public education advocates who opposed the bill argued it will drain resources from public schools and primarily benefit students from wealthy families.

Kemp also signed Senate Bill 351, sponsored by nine Republican senators, which will require social media companies, as of July 1, 2025, to verify their users are at least 16 years old unless they receive approval from a parent.

House Bill 409, sponsored by Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, directs school systems to consider not having bus stops where a student would have to cross a roadway with a speed limit of 40 mph or greater. The bill also increases the penalty for passing a stopped school bus to $1,000 from $250.

Kemp noted that Ashley Pierce, the mother of Addy Pierce, an 8-year-old who was fatally struck by a motorist as she boarded her school bus, “passionately advocated for and was instrumental in the passage of this legislation.”

Senate Bill 395, sponsored by Sen. Clint Dixon, R-Gwinnett, states that no school visitor or personnel can be prohibited from possessing an opioid reversal drug such as Narcan and directs schools to maintain a supply. It also allows opioid antagonists to be sold in vending machines and directs certain government buildings to maintain a supply of at least three doses.

Senate Bill 464, also sponsored by Dixon, creates the School Supplies for Teachers Program to financially and technically support teachers purchasing school supplies online. It also creates an executive committee of five voting members within the Georgia Council on Literacy and limits the number of approved literacy screeners to five, one of whom must be available to schools for free.

Health care

The governor chose his hometown of Athens as the venue to sign several bills aimed at improving health care in rural and underserved communities.

Among them was House Bill 1339, sponsored by Rep. Butch Parrish, R-Swainsboro, which revises the Certificate of Need process by which the state determines if and how new medical facilities can be built or expanded. The bill provides for several new exemptions, including psychiatric or substance abuse inpatient programs, basic perinatal services in rural counties, birthing centers and new general acute hospitals in rural counties. It also raises the total limit on tax credits for donations to rural hospital organizations to $100 million from $75 million.

Senate Bill 480, sponsored by Sen. Mike Hodges, R-Brunswick, establishes student loan repayments for mental health and substance use professionals serving underserved youth in the state or in unserved geographic areas disproportionately impacted by social determinants of health.

House Bill 872, sponsored by Rep. Lee Hawkins, R-Gainesville, chair of the House Health and Human Services Committee, expands cancelable loans for certain health care professionals to dental students who agree to practice in rural areas.

Senate Bill 293, sponsored by Sen. Ben Watson, R-Savannah, chair of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, reorganizes county boards of public health and opens the qualifications for the CEO of each county board of health to include either licensed physicians or people with a master’s degree in public health or a related field.

Military members and veterans

Kemp on Wednesday focused on bills to improve military recruitment and provide more work opportunities for veterans and military family members.

House Bill 880, sponsored by Rep. Bethany Ballard, R-Warner Robins, allows spouses of military service members to work under a license they hold in good standing in another state while under the supervision of an existing Georgia medical facility or provider.

Senate Bill 449, sponsored by Sen. Larry Walker, allows military medical personnel to practice for 12 months while a license application is pending, including working as a certified nursing aide, certified emergency medical technician, paramedic or licensed practical nurse. The bill also creates a new advanced practice registered nurse license and makes it a misdemeanor to practice advanced nursing without a license.

Human trafficking

The governor on Wednesday was accompanied by first lady Marty Kemp and other members of the GRACE Commission for the signing of an anti-human trafficking package. It includes Senate Bill 370, which adds certain businesses to the list of organizations that must post human trafficking notices, including convenience stores, body art studios, businesses that employ licensed massage therapists and manufacturing facilities.

Sponsored by Sen. Mike Hodges, R-Brunswick, the bill also allows the Georgia Board of Massage Therapy to initiate inspections of massage therapy businesses and educational programs without notice and requires massage therapy board members to complete yearly human trafficking awareness training.

House Bill 993, sponsored by Rep. Alan Powell, R-Hartwell, creates the felony offense of grooming of a minor and creates new penalties for offenses relating to visual mediums depicting minors engaged in sexually explicit conduct.

House Bill 1201, sponsored by Rep. Houston Gaines, R-Athens, allows human trafficking survivors who received first offender or conditional discharge status to vacate that status for certain crimes, as long as the crime was a direct result of being a victim of human trafficking.

Coastal communities

Earlier today in Brunswick, Kemp signed legislation impacting Georgia coastal communities, including House Bill 244, which amends the laws around how wild game can be hunted and how seafood dealers operate, and House Bill 1341, which designates white shrimp as the state’s official crustacean.

Taxes

Earlier this month Kemp signed several bills related to taxation, including House Bill 1015, sponsored by Rep. Lauren McDonald, R-Cumming, which lowers the state income tax for tax year 2024 to 5.39%, accelerating a multiyear drop in state income taxes that started at 5.75% in 2023 and will continue through 2029.

The Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget estimates the tax cut acceleration will save Georgia taxpayers approximately $1.1 billion in calendar year 2024 and about $3 billion over the next 10 years.

Kemp also signed House Bill 1021, sponsored by Rep. Lauren Daniel, R-Locust Grove, which increases the state’s income tax dependent exemption to $4,000 from $3,000.

House Bill 581, sponsored by Reps. Shaw Blackmon, R-Bonaire, and Clint Crowe, R-Jackson, enables a constitutional amendment (House Resolution 1022) to let voters decide whether counties can provide a statewide homestead valuation freeze, which limits the increase in property values to the inflation rate.

The governor has until May 7 to sign or veto bills passed during the legislative session that ended on March 28. Those he takes no action on will automatically become law.

Legislation signed by Kemp is posted on the governor’s website.

Read these related stories:

Have questions, comments or tips on education in Georgia? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected].

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSGA

Instagram @STATEAFFAIRSGA

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Incumbent candidates for local, federal races likely to be no-shows at this weekend’s primary debates

ATLANTA — One of Georgia’s prominent media organizations is pleading with incumbent state and congressional candidates to participate in its primary election debates slated for Sunday.

For the first time in The Atlanta Press Club’s 30-year debate history, incumbents facing challengers in the May 21 primary have either declined or not yet committed to participating in the organization’s well-known debate series. The possible no-shows include candidates in four Congressional races as well as the Georgia Supreme Court, and the Fulton County District Attorney races.

“This is the first time that we’ve had so many [incumbents] not participate,” debate organizer Lauri Strauss told State Affairs. Strauss declined to speculate why candidates aren’t participating.

Hoping to encourage more participation, the organization issued the following statement:

“The Atlanta Press Club believes it is the responsibility of people running for public office to answer questions from their local media that will help inform voters before they cast their ballots. If a candidate is running for public office, the candidate should be willing to participate in the democratic process, which includes attending debates and fielding questions from journalists and opponents.”

Candidates have until Friday to RSVP.

Strauss said candidates who fail to appear will be represented on stage by an empty podium during the debate.

District Attorney Fani Willis has declined to participate and Democratic U.S. Reps. Lucy McBath and David Scott have yet to RSVP. Strauss said the organization is still in talks with Georgia Supreme Court Justice Andrew Pinson’s staff about his appearance in the debate.

Willis, declined earlier this week to participate, citing constraints around talking about sensitive cases like the criminal prosecution of former President Donald Trump.

McBath currently represents the 7th Congressional District and is now running in the newly drawn 6th Congressional District against two Democratic challengers, Jerica Richardson and Mandisha Thomas. McBath declined to participate in the press club’s general election debate in 2022, forcing her Republican challenger Mark Gonsalves to debate with an empty podium. McBath won with 61% of the vote.

The debates will air live on April 28 on GPB.org, on The Atlanta Press Club’s Facebook page (www.fb.com/TheAtlantaPressClub). It will be rebroadcast in early May on WABE.org.

| Race | Tape and Livestream Sun. April 28 |

GPB-TV Broadcast | WABE Broadcast |

| Congressional District 6 Democrats | 10:00 a.m. | April 29 at 7:00 p.m. | May 1 at 4:30 p.m. |

| Congressional District 13 Democrats | 11:15 a.m. | April 28 at 4:00 p.m. | May 1 at 5 p.m. |

| Congressional District 3 Republicans | 1:00 p.m. | April 28 at 5:00 p.m. | May 2 at 3:30 p.m. |

| Congressional District 2 Republicans | 3:00 p.m. | April 29 at 5:00 p.m. | |

| Georgia Supreme Court | 4:45 p.m. | May 2 at 4:30 p.m. | |

| DeKalb County CEO | 5:45 p.m. | May 2 at 5:15 p.m. | |

| Fulton County District Attorney | 6:45 p.m. | May 1 at 4 p.m. |

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected] and Tammy Joyner on X @lvjoyner or at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram@StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

‘It is nothing short of insane:’ Bill to criminalize squatting signed by governor

ATLANTA — Today Gov. Brian Kemp signed legislation criminalizing squatting, the illegal practice of entering and residing on someone else’s property without their consent.

The Georgia Squatter Reform Act makes squatting a misdemeanor criminal offense, punishable by up to a year in jail, a $1,000 fine, or both. It also speeds up the timeline to evict a squatter, giving landlords and law enforcement more tools to establish that someone is trespassing and to demand that they leave.

“It is nothing short of insane that there are some who are entering other people’s homes and claiming them as their own,” Kemp said in a post on X after signing the bill at the state Capitol. “Thanks to our legislative partners, I was proud to sign HB 1017 — once again making it clear that illegal squatters are criminals, not residents.”

Over the past few years, squatting has become more prevalent in Georgia, with trespassers breaking into vacant homes, claiming tenancy and refusing to leave.

A 2023 survey of institutional investors in single-family rental homes who are members of the National Rental Home Council found there were 1,200 illegally-occupied homes in and around Atlanta. Realtors told State Affairs they’ve encountered squatters in homes for sale and rent in Gainesville, Valdosta and Albany.

Until now, law enforcement in many jurisdictions treated the issue as a civil matter, telling property owners to file eviction actions in court, which could take months or even years to resolve.

The new law directs local law enforcement to issue citations and arrest people accused of squatting if they don’t provide a valid lease or proof of payment within three days. If they do produce such documents, it moves eviction proceedings to magistrate courts, and requires cases to be heard within seven business days after filing.

If the judge deems documents they present to be forged or fake, those accused of squatting could be charged with a felony. And judges can impose more fines based on the fair market value of rent that landlords lose.

On hand in the governor’s office for the signing was Rep. Devan Seabaugh, R-Marietta, the lead sponsor of the bill.

“Currently in Georgia law, we’re giving squatters tenant rights,” Seabaugh previously told State Affairs. “And my bill would take that away. It basically says, ‘You’re an intruder, you’re a criminal, and we’re going to treat you like a criminal.’ ”

Read these related stories:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs

State troopers are stretched to fight drugs and curb highway deaths

ATLANTA — When Cpl. Anthony Munoz straps on his bullet-proof vest each day and pulls out of the Department of Public Safety headquarters in Atlanta, Munoz never knows how his shift will unfold. What is for certain is that the traffic — of cars, criminals and contraband — is constant.

And what is also true is that there are not nearly enough state troopers on the road to catch them all.

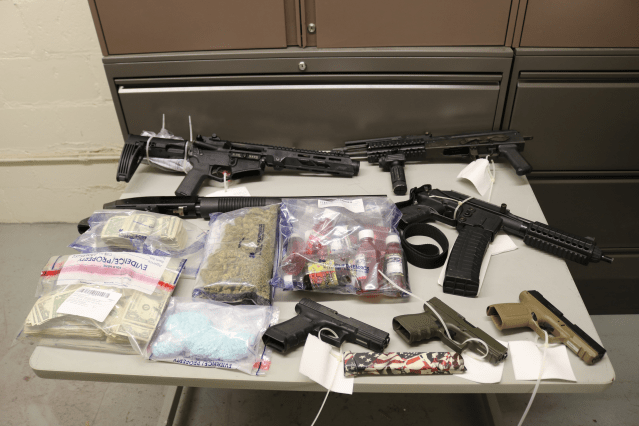

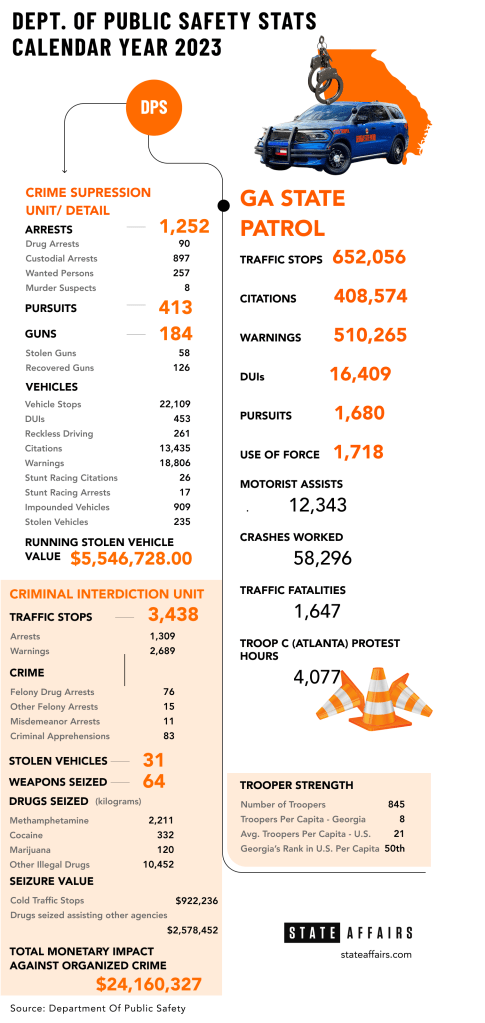

A 13-year veteran, trooper Munoz, 45, is part of the department’s Criminal Interdiction Unit, whose main focus is suppressing the robust illegal drug trade flowing through Georgia. Last year the eight-member team made 1,309 arrests, including 76 felony drug arrests, and helped other agencies seize $24 million worth of contraband.

In 2019, the unit had 25 members.

Capt. Greg Shackleford, the troop commander, said that in 2020 the unit was split up and half the team was sent to Georgia State Patrol posts around the state, which were hurting for staff, to conduct the Department of Public Safety’s core functions — traffic enforcement and responding to car crashes.

The split has translated into Munoz and the rest of his team now spending most of their time monitoring Interstate 20 just south of Atlanta, and Interstate 75/85 west of the city. He said they regularly support the investigations and busts of other local and federal agencies, and frequently join the governor’s crime suppression details, which have included taking down car thieves and street racers.

All this leaves his team with less time to develop intelligence on their own drug cases and to snare more traffickers. It also means the troopers no longer have time to monitor roads in rural areas in south Georgia where, Shackleford said, many drug traffickers driving trailers full of drugs and contraband enter the state on highways coming from Florida and Texas and now ride around unchecked for hundreds of miles.

Chronically understaffed

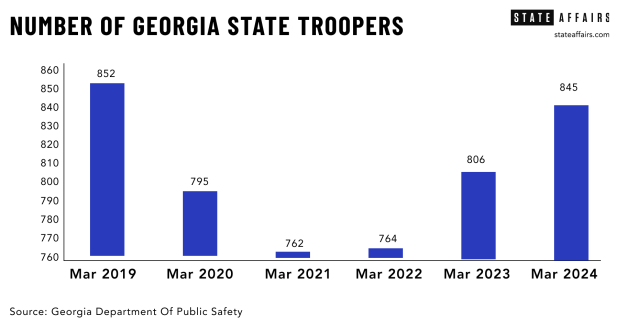

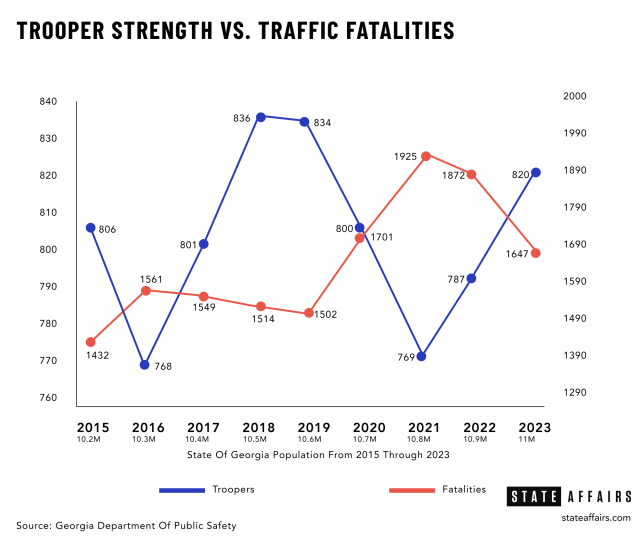

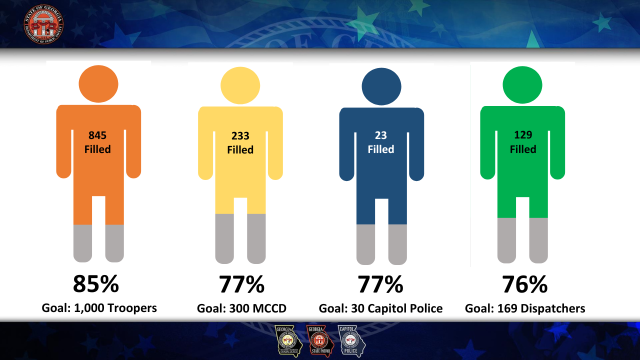

The Georgia State Patrol remains chronically understaffed. While the state’s population has grown, and with it the number of motorists, car crashes and criminal activity, the number of state troopers has hovered stubbornly between about 750 and 850 for over a decade, giving Georgia the unwanted distinction of having lowest number of troopers per capita in the country.

The average number of state troopers per capita in the U.S. is 21; for Georgia, it’s eight. And the outlook for changing that is not great, Col. William “Billy” Hitchens, the public safety commissioner, told legislators during hearings last fall — Unless the state makes bold moves in improving compensation. He said Georgia State Patrol has “aimed to reach 1,000 troopers for as long as I have been employed,” which is 30 years.

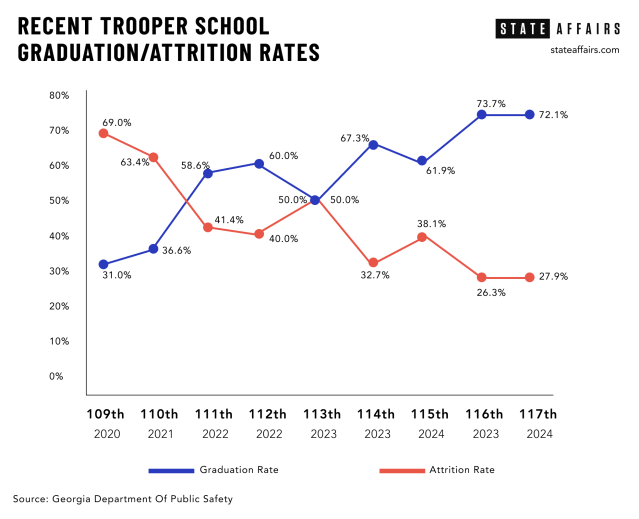

The state saw its trooper numbers plummet to 745 during the pandemic in 2021. The agency is now back to 845 troopers. The current trooper school started with 61 candidates, and if recent history is a guide, about 70% will graduate in September and put on the badge.

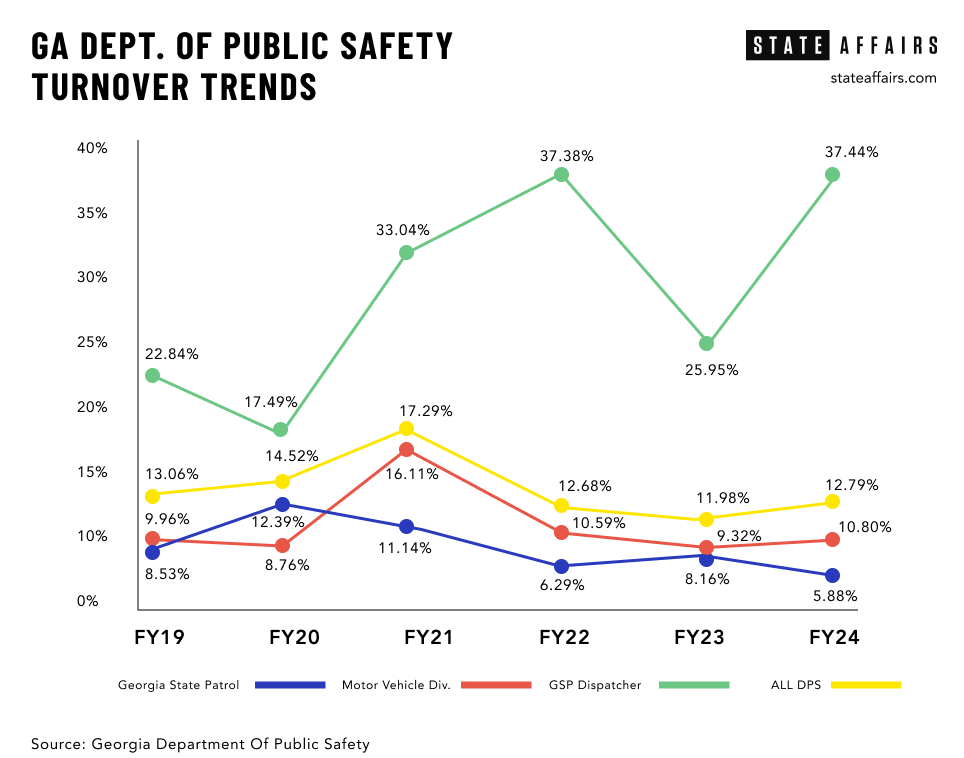

While “things are moving in the right direction” this year in terms of recruitment, said Hitchens, he said too many veteran officers are either resigning or retiring early.

Between 2018 and 2023, 48 troopers left the agency on a full-service retirement, meaning they had served for 30 years. During the same period, 341 troopers resigned, retired early or departed for other reasons. As it costs the department $153,397 to train a trooper, those who left early cost the state $52 million, said Lt. Col. Josh Lamb, director of administrative services for the Department of Public Safety.

Fewer troopers means more highway deaths

Fewer troopers on the state’s roads impact everyone, say law enforcement officials. .

“As our trooper strength decreases, traffic fatalities increase,” said Hitchens.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration data shows a direct inverse relationship between trooper staffing and the number of fatalities in Georgia. At its low ebb in 2021, with 769 troopers, 1,925 people died on Georgia roads. More recently, in 2023, with 820 troopers, Georgia saw 1,647 fatalities, an 8% decrease over 2022.

“We are concerned with traffic patterns, the way people drive, and we enforce the law out there,” Hitchens told State Affairs. “When you start losing personnel, whether it’s the state, or cities and counties, one of the first things that may be taken away is traffic enforcement. Because they’re responding to other calls — robberies, domestics, you name it. And when troopers stop doing it, there are just fewer people out there reminding you, ‘Hey, that’s dangerous. Slow down.’ ”

The state patrol wrote 408,574 citations to motorists last year, but issued even more warnings — 510,265. Hitchens noted that mere trooper presence on the highway is a strong deterrent.

“It doesn’t have to be you that gets stopped,” he said. “Those 50 cars that ride by during that time and see that patrol car, go ‘Ooh, I don’t have my seatbelt on … I’m playing with my phone,’ and it just impacts that behavior. But the less officers you see on the road, the less you have people changing their driving behavior.”

Along with encouraging safer driving, DUI enforcement has become a higher priority for the department. A “Nighthawks” squad of 22 officers patrols after midnight in areas of the state where data analysis shows high incidences of alcohol and drug-induced crashes and violations. The state patrol made 16,409 arrests for driving under the influence in 2023.

Hitchens said the work of such special units is compromised when they’re pulled into other duties due to statewide manpower shortages. The three Nighthawks units, for example, are often pulled into other traffic stops and crime suppression details in Atlanta, Macon and Columbus. And drug interdiction officers have had to cover vehicle crashes and multiple public protests over the Atlanta Public Training Center (dubbed “Cop City”) and, more recently, conflict between Israelis and Palestinians in Gaza.

Besides securing troopers, Hitchens said the department is struggling to recruit dispatchers, who are the lifeline for troopers and officers who patrol alone and depend on dispatchers to provide critical information quickly. Today, the department has 129 dispatchers who work at nine regional call centers. They need 169 to be fully staffed.

A tough sell in the ‘Cop City’ era

Hitchens told lawmakers that heightened public criticism of law enforcement over the past few years has played a role in the department’s ongoing challenges to recruit and retain officers.

“People without understanding of what it’s like to be involved in a rapidly evolving life and death situation started scrutinizing officers, cities started defunding their police departments while demanding greater accountability and more training, both of which cost money,” he said. “Following the George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks and Breonna Taylor instances, the media and some leaders in our community nationwide began to demonize the police.”

Hitchens said that since the death of Manuel Teran, a protester against the planned Atlanta Police Training Center who was allegedly shot by a Georgia trooper during a firefight on the forested property in 2023, and the sometimes violent public demonstrations that ensued, “that dynamic just got worse. For a long time with ‘Cop City,’ it was constant protest, and you know, that weighs on you.”

Munoz, who was patrolling with other local law enforcement on the perimeter of the training center site the day Teran died, said the public’s jaundiced view of that episode and other recent struggles between police and citizens that have gone viral on social media can be frustrating.

“I know that a lot of the narrative out there is not true at all,” he said. “There are millions and millions of police encounters every day. And those [violent] ones are fractions of a percent of incidents, and whether a trooper or officer responds the right way, it all boils down to compliance. If you just comply, you’re presumed innocent, you’ll have your chance to make your case, and the facts will come out. Don’t argue, don’t fight, don’t resist. We don’t want to fight you.”

Noting that he has a wife and four children he wants to come home to, Munoz said, “We’ve been pounded with de-escalation in training, and that’s what we practice. I’m sure there are officers out there now that freeze and that say, ‘Do I do my job? Or am I going to be put in prison, because I reacted in a certain way?’ So we do carry that, and it’s a heavy, heavy burden.”

Last year three House Democrats introduced House Bill 107, the Police Accountability Act, which proposes an end to qualified immunity for law enforcement officers and would have required body-worn cameras for all peace officers. The bill did not advance out of committee, but Hitchens said taken together with the public unrest and anti-police sentiment since 2020, it all had a demoralizing effect on his officers.

“All of these factors are forcing officers to become fatigued with our profession,” he said. “They feel that support is ending and the job is not worth the risk.”

According to the Georgia Peace Officers Training and Standards (POST) Council, the number of officers with basic council certifications in Georgia dropped to 5,956 in 2023 from 6,666 in 2017.

“I don’t think there’s a single law enforcement agency in Georgia that is fully staffed,” said Chris Harvey, deputy executive director of Georgia POST. “And they have a very hard time getting qualified people on board. … There just aren’t enough quality people that are interested in doing this job.”

While some agencies have raised salaries and added signing bonuses, he said, “I can tell you that it’s not a solved problem. Because I don’t think it’s primarily a money issue. I think it has a lot to do with the difficulty of doing this job these days. I’m not sure it’s ever been harder to work in law enforcement. The amount of scrutiny along with the amount of violence that police officers encounter on a regular basis, they generally feel like they’re out there alone. If they make one mistake, they’re gonna pay dearly for it. … It’s a tough sell.”

Father and son patrol leaders fight for trooper compensation

For Hitchens, his push to recruit potential state troopers and convince state leaders to increase pay and benefits for troopers is supported by an unlikely suspect — his dad.

House Appropriations public safety subcommittee chair Rep. Bill Hitchens, R- Rincon is a former trooper who served in the Georgia State Patrol for 28 years, and was later appointed by former Gov. Sonny Perdue to serve as public safety commissioner from 2004 to 2011. The elder Hitchens has served in the House since 2013.

At the House Working Group on Public Safety meeting last fall, Rep. Hitchens noted that the state patrol has maintained around 700 troopers since he joined in 1969, when the state population was about 4 million. “Now it’s 11 million people … and we have a lot more murders, stolen cars and merchandise,” the elder Hitchens said. “Where we fell down, I don’t know. It’s just we’ve never grown. … And now we’re at a breaking point.”

The younger Hitchens was appointed by Gov. Brian Kemp as deputy commissioner for public safety in 2020, and then as commissioner in 2023. As commissioner he oversees the Georgia State Patrol, the Motor Carrier Compliance Division, the Capitol Police Division, and other special law enforcement units, including the crime suppression, SWAT and canine teams.

The son and father team have successfully fought for substantial pay raises for troopers, whose salaries have increased over the past three legislative cycles by nearly $17,000. That includes a 4% cost of living increase and a $3,000 bonus for law enforcement officers approved by the General Assembly in the fiscal year 2025 budget. The starting salary for a new trooper will be $63,684 as of July 1, if the governor approves it in the budget, as expected.

Dispatchers will also get a boost in next year’s budget, with new pay step increases that can take them from a starting salary of $39,000 to up to $56,000 as they earn promotions.

Col. Hitchens said those pay bumps seem to be turning the tide on recruitment. The number of applicants and graduates rose for the last few trooper schools held over the past year. Other changes the department made to trooper school requirements have also helped, including allowing people to go home more often during training, permitting access to mobile phones at night, and allowing people with arm tattoos to train and serve, if they cover them with long sleeves.

“We tried to make changes in training that we felt like really didn’t help people stay,” said Hitchens. “And we didn’t make it kinder or gentler. I mean, in this job that you sign up for, there’s got to be a certain level of discipline, there’s got to be a certain level of respect, with high physical training standards, that’s still there. But the things that we could change, we decided to do.”

Both men remain concerned about how to stem the trend of early retirement, and agree that sweetening the retirement package is the key way to combat it.

Currently most troopers qualify for a pension equal to 1% of their final pay for every year of service, and can also participate in a 401(K) savings plan while they serve, which the state matches up to 9%, depending on their number of years on the force. But Col. Hitchens is pushing for a more generous “defined benefit” retirement plan, with a 3% pension, which he said would double what most troopers get when they retire. Instead of earning about $25,000 a year on average, they would receive about $52,000.

Presently, the average tenure of a state trooper is 10 years, nowhere close to the 30-year careers Hitchens and other leaders want his officers to pursue.

And he knows it matters to them, as retirement benefits emerged as the number one retention issue on a recent agency-wide, anonymous survey.

“Every other agency is increasing their hiring packages, raising pay and offering better benefits, from retirement to free health care,” Hitchens said, noting that the Atlanta and Sandy Springs police departments offer substantially higher pay and 3% defined benefit plans.

“We’re in a competitive bidding process, and we have to offer a reward that’s worth the risk our people are taking with their lives and liberty.”

The tenure of senior officers also matters because of the crucial role they play in mentoring new recruits.

“When we have our young troopers, the men and women that come into the field, they’re excited,” said Shackleford, the troop commander, who spent much of his 36-year public safety career in SWAT before taking over Troop K, which includes the crime suppression, criminal interdiction, K-9, SWAT and dive units. “They see the fast cars, they want to get into something. And the problem is, it’s just like a puppy. A puppy’s gonna get into something and make a mess. So we need the older ones to kind of calm them down and guide them a bit, show them how to see and assess a situation.”

Such role modeling of behavior, said Hitchens, “is very important, especially with de-escalation. A senior officer, having dealt with so much of that, has that confidence and the competence to carry out [their] job in a way that I think a lot of younger, less experienced officers don’t have yet. And that’s how you learn and morph over a career,” said Hitchens, adding that that transfer of knowledge and practice from veterans to recruits “benefits the public as well.”

Rep. Hitchens co-sponsored two bills related to bolstering retirement plans for law enforcement that passed out of the retirement committee during the last session. One passed in the House, but did not get a vote in the Senate. Other lawmakers balked at the cost.

Read these related stories:

Have questions or comments? Contact Jill Jordan Sieder on X @journalistajill or at [email protected]

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

X @StateAffairsGA

Instagram @StateAffairsGA

Facebook @StateAffairsGA

LinkedIn @StateAffairs