Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoA David and Goliath story: Why it was hard to legislatively cut health care costs

(Credit: Maudib)

- Indiana’s health care costs are higher than they should be, driven at least in part by high market concentration in both Indiana’s hospital and insurance industries.

- State lawmakers passed three Republican priority bills aimed at reducing health care costs this legislative session, but some argued the legislation didn’t go far enough or address the whole puzzle of what drives high hospital prices.

- The health care industry is influential in the Indiana Statehouse, both as one of the top employers in the state and as a prolific contributor to political campaigns.

At the start of the legislative session, lawmakers pushing for health care cost-cutting bills knew they faced a challenge.

So much so that they nearly all used the same biblical tale to describe the situation: It was like David and Goliath. In their eyes, the legislatively powerful nonprofit hospitals were the giant Goliath and lawmakers were the smaller, weaker David, working to pass bills that could limit hospitals’ profits and in turn — they hoped — lower Indiana’s high health care costs.

Indiana lawmakers passed three Republican priority bills this legislative session aimed at reducing such costs, ranging from limiting physician noncompete agreements to creating benchmarks for how high hospital prices in the largest hospital systems should be.

While those carrying the bills lauded the progress, not everyone agrees the new laws, which are poised to start going into effect in the next couple of months, will reduce costs without dangerous unintended consequences.

Depending on who you ask, that’s because lawmakers weren’t looking at the complete puzzle of what drives high hospital prices, such as Medicaid reimbursement rates or the role of pharmaceutical companies, or because the measures were significantly watered down throughout the legislative session. Or maybe both.

For example, lawmakers removed a fine in House Bill 1004 for hospitals that charged high prices, and a bill reducing prior authorization requirements never crossed the finish line. And instead of banning all physician noncompetes, Senate Bill 7 just prohibited them for primary care physicians.

“Senate Bill 7 was a stone to throw at this Goliath as it passed the Senate,” Rep. Ethan Manning, R-Logansport, mused during a committee hearing in the second half of session. “As amended, I think we’re throwing a wiffle ball.”

The health care industry is one of the top employers in the state and generates nearly 15% of the state’s gross domestic product, so it’s all but unavoidable that the debate would be routinely muddied by the influential employers involved in it. Some of the state’s biggest employers are health care giants that sit just roughly a mile from the Statehouse, including Elevance Health (previously known as Anthem), Eli Lilly and Indiana University Health.

Still, the Indiana Hospital Association and the Indiana Insurance Institute rejected the notion that either of their industries was Goliath-like.

Likewise, those in the health care industry don’t always agree on which data to rely on and blame costs on other factors — or sometimes each other — making it difficult to pinpoint easy solutions.

There’s also simply ideological qualms over too much government involvement and a fear of unintended consequences, such as the potential closure of hospitals that provide valuable care in rural communities or an inadvertent increase in health insurance premiums.

“There seems to be this short sighted focus on ‘doing something’ to a certain number of facilities without a recognition of the consequences to the entire health care system around the state,” said Brian Tabor, president of the Indiana Hospital Association. “We kind of missed the opportunity to have a broader discussion.”

Which bills were signed into law

Lawmakers made lowering hospital costs a priority this legislative session after multiple reports found that Indiana’s health care costs are higher than they should be, driven at least in part by high market concentration in both Indiana’s hospital and insurance industries.

Health insurance premiums make up a larger share of a Hoosier worker’s salary than of an average American and there’s a large gap between what Medicare pays for hospital services compared to what commercial insurance pays in Indiana, signaling a high hospital cost problem.

The result was three new laws signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb, all of which were priorities of Republican legislative leaders.

House Bill 1004, which received the most attention throughout the legislative session, no longer contains its most controversial measure — fining hospitals that charge more than 260% the cost of Medicare. Instead, the final legislation requires the state to collect data on when Indiana’s largest hospital systems charge more than 285% the price of Medicare.

Starting in July, the new law will also require nonprofit hospital systems to charge for services based on where the service is actually provided. Currently, health providers can charge more for a procedure if it’s performed at an off-site, hospital-owned clinic — as if it were being performed at a hospital — rather than an independent clinic.

Representatives from hospitals say that flexibility allowed them to treat patients where they are, instead of requiring them to travel to hospitals, but it also can mean higher costs for patients. Just like in the other part of the bill, there are numerous carve-outs, including for rural hospitals, oncology centers and behavioral health centers.

The legislation also encourages hospitals and insurance companies to participate in a program that would reduce prior authorization and gives physicians who own their own practices a tax credit.

Some lawmakers saw the bill as a good start, a way to get more data, while others viewed much of it as a do-nothing bill targeting a small subset of hospitals.

“We squandered the opportunity to help Hoosiers facing high health care costs,” Evansville Democratic Rep. Ryan Hatfield told State Affairs, “and instead passed a feel-good bill that will have little implications for the consumer.”

Lawmakers also approved Senate Bill 8, which requires pharmaceutical benefit managers, who negotiate agreements with drug manufacturers for insurance companies, to pass along discounts to those who are insured, and Senate Bill 7, which bans noncompete agreements between hospitals and primary care physicians.

Getting the three measures passed was so challenging that the latter barely crossed the finish line, due primarily to philosophical issues about the role of government and whether or not the state should limit noncompete agreements for one industry and not others. Even a Democrat, Hatfield, questioned why Indiana Republicans were more in-sync with Democratic President Joe Biden on the issue.

A House committee had to vote twice on the measure after it failed to obtain enough votes to advance the first time, a rare occurrence at the Statehouse.

Health care influence at the Statehouse

Lawmakers on both sides of the bills blamed how convoluted the process of lowering health care costs can be on the prowess of the health care industry, and the sheer number of groups and lobbyists with an interest in the debate.

“It’s a behemoth. We’re talking about billion-dollar companies and folks that are making millions of dollars,” said Sen. Justin Busch, the Republican from Fort Wayne who carried SB 7. “Any time you step into a world where folks are making a ton of money, and we’re talking about really, really big business here, I think it’s going to be difficult every time.”

Both insurance and hospital groups frequently contribute to Statehouse candidates, with the top five insurance companies and the Indiana Insurance Institute contributing more than $1 million over a five-year period to state candidates and committees. Hospitals spent at least $600,000 as well.

Meanwhile representatives from both industries spent in the hundreds of thousands on lobbying efforts and entertainment at the Statehouse in 2022. (The 2023 reports aren’t yet available).

Those advocating for the bills, primarily in the business community, have their own powerful connections, too. Al Hubbard, an influential Republican who once served in the White House, leads Hoosiers for Affordable Healthcare.

Andy Downs, director emeritus at the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics at Purdue-Fort Wayne, said it’s not that lobbying or campaign contributions guarantee a candidate will vote in line with your goals.

“What they are much more likely to guarantee is access,” Downs said. “If you give $2,500 to your favorite candidate, your favorite candidate is probably going to answer your call when you call, which means you may be in a better position to argue your point.”

On the hospital’s side, that increased access meant the opportunity to cast doubt on studies completed by the RAND Corporation, a nonpartisan think tank, that showed hospital prices were higher than they should be. Hospitals took issue with the methodology, though multiple studies confirm Indiana has a high health cost problem.

Valparaiso Republican Sen. Ed Charbonneau, the sponsor of House Bill 1004, said the dispute over the validity of the numbers impacted discussions on health care costs. In the end, House Bill 1004 primarily collects more data, instead of relying on the data that already exists to take action.

The insurance fight was less obvious. House Bill 1003, which originally would have limited prior authorization requirements for physicians with a good track record, was dramatically weakened after the Insurance Institute of Indiana testified against it. The amended language, which just encourages insurance companies to limit prior authorization, was later placed in House Bill 1004.

Rep. Hatfield argued Republican lawmakers put too much emphasis on punishing a select few hospitals and not enough on insurance companies. He said lawmakers were fearful of upsetting Anthem, which is headquartered just a mile away from the Statehouse.

“I genuinely do not believe that it’s the unintended consequences that lead to inaction,” Hatfield said, “but rather the hold by the special interests, in particular the insurance companies and the insurance industry, over the legislative process that prevents us from taking bold action on health care costs.”

The Indiana Insurance Institute, though, said it was equally impacted by the bills that legislators passed. Another bill that was not dubbed a priority bill among legislative leadership requires insurance companies to speed up the prior authorization timeline and creates a pilot program reducing prior authorization for state employees.

Marty Wood, president of Indiana Insurance Institute, argued lawmakers were likely also influenced by another health care entity, this time pharmaceutical Eli Lilly. The company, which has contributed $246,000 to candidates and other state committees in the last five years, did not respond to a question about if it was involved in this year’s health care cost debate. However, the company called SB 8, the pharmacy benefit manager bill, “ground-breaking legislation.”

Unintended consequences

Some lawmakers still worry that the new laws, however watered down they may be, will have unplanned outcomes on health care access throughout out the state.

“I’m worried that what we’re doing is going to minimize that quality and access for everybody,” Sen. Jean Leising, R-Oldenburg, told State Affairs. “So then, will it have rippling effects to my small hospitals in my district?”

While some hospitals across Indiana are still collecting much more than they spend, others are struggling after the pandemic. Just this week, Community Health Network announced it would be cutting jobs, and a recent report found that seven unnamed rural hospitals in Indiana are at risk of closing.

Already, a third of Indiana’s counties have no inpatient delivery services, and 8% of the state is located more than 45 minutes away from a trauma center.

“They like their hospitals,” Carmel Republican Rep. Donna Schaibley, the author of House Bill 1004, said of her fellow lawmakers. “Sometimes I think they have trouble disengaging what’s going on as far as hospital administration and wonderful doctors and nurses that take care of you every day.”

During the legislative session, hospitals and insurance companies advocated for a different way to cut health care costs for Hoosiers: increase Medicaid reimbursement rates for hospitals, so less of the costs are shifted onto those with private insurance. The base Medicaid rates haven’t been increased in decades.

“It’s a choice the legislature is making and they understand that there’s a cost shift going on,” Wood said, “but right now, they’re pointing the finger rather than addressing their own part of the problem.”

Holcomb’s administration is planning to review reimbursement rates for hospitals during the next budget cycle, but Tabor warned that could be too late for struggling hospitals. It’s also unclear if that answer would do much to lower health costs: Both Michael Hicks, a Ball State University economist, and Seth Freedman, an Indiana University professor specializing in health economics, cast doubt on the concept of cost shifting.

“What that’s kind of assuming is that the providers have some way of raising prices to their private paying patients that would increase their profit on those patients, but they’re only going to do that if Medicaid pays the low prices,” Freedman said. “That doesn’t really make sense right? If they can raise prices on their private payers, we expect them to do it anyway, no matter what Medicaid payment rates are.”

During the debate on House Bill 1004 the final night of session, Sen. Jean Breaux, D-Indianapolis, shared perhaps the most transparent take on the dilemma lawmakers faced when dealing with the complex issue of cutting health care costs.

“I feel like just throwing up a coin and whichever side it falls on,” she said, before voting against the bill. “I really don’t know what’s the best thing to do here.”

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsins

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: Lawmakers passed multiple bills this legislative session with a goal of cutting health care costs. (Credit: Maudib)

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

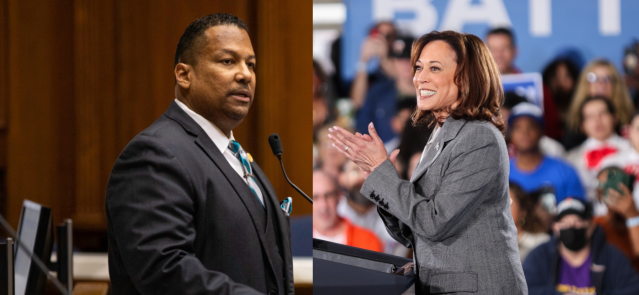

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …