Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoHoosiers are paying more for hospital care. Here’s how lawmakers want to solve the problem.

Members of the Indiana General Assembly clap in response to legislative changes proposed during the 2023 State of the State Address on Jan. 10, 2023, at the Indiana Statehouse. (Credit: Ronni Moore)

Update, May 16, 2023: Gov. Eric Holcomb has signed three Republican priority bills aimed at reducing health care costs. Read about the final versions of the bills here.

The Gist

Multiple studies show Indiana has relatively high health care costs — both when it comes to hospital costs and insurance premiums, which can mean that a large chunk of the money Hoosiers earn goes toward health care.

Both House and Senate Republicans have made lowering those costs a priority this legislative session after sending a warning letter to hospitals last year asking them to address the high costs themselves. Plans include a proposal from House Republicans to impose fines on hospitals with high prices.

Lawmakers’ proposals are likely to be met with intense pushback from hospitals.

What’s happening?

Health insurance is less affordable in Indiana based on workers’ average annual pay than the U.S. as a whole, a report from the Nicholas C. Petris Center found. On average, premiums for an individual were 14.1% of a workers’ annual average pay in Indiana, compared to 11.2% in the U.S. as a whole in 2020.

Right now, the average employer-sponsored premium is $7,319 for a single person per year in Indiana. While that’s only $170 higher than the national average, individual premiums would need to decrease by more than $1,500 per year in order to match the U.S.’s premium cost in terms of affordability. In short: Hoosiers are paying too much on monthly premiums, based on what they make.

Likewise, there is a larger gap between what Medicare pays for hospital services compared to what commercial insurance pays in Indiana than in all but six states, according to a study from the RAND Corporation, signaling a high-cost problem for Hoosiers when it comes to hospital care.

A study from Harvard University professors arrived at a similar finding: Hospitals in Indiana, of all the states, would lose the second highest percentage of their revenue if commercial rates matched Medicare rates, based on 2017 numbers.

Health care expenditures per capita in 2020 in Indiana were higher than that of the U.S., according to a separate Petris Center report commissioned by the Legislative Services Agency. That statistic matters in a state with a reputation as a low-cost-of-living state with average pay that is significantly lower than that of the U.S.

The Indiana Hospital Association (IHA) said some critics have become hyper-focused on only a small portion of the picture in a “deliberate misrepresentation to advance their agenda.”

“Hospital prices may be relatively higher, [but] they’re not nearly as high as some of our critics say,” said Brian Tabor, president of the IHA.

For example, Indiana is below the U.S. rate for health care expenditures per enrollee when looking just at those that are privately insured, according to the Legislative Services Agency’s Petris Center report.

So why are prices high?

A variety of factors impact health care costs, making it challenging to pinpoint just one silver bullet.

Hoosiers for Affordable Healthcare largely blame the insurance and hospital markets in Indiana, both of which are considered highly concentrated. Indiana’s health care system is dominated by six major hospital systems, and the top insurer in the market— Anthem

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Indiana, has an average market share of 44.9% across Indiana’s metropolitan statistical areas.

“Prices are high in Indiana, because they can be,” said Matt Bell, a lobbyist for Hoosiers for Affordable Healthcare, “because there has not been significant push from the employer community to demand lower prices, because our hospitals are more consolidated than in other states and that has driven prices as we’ve consolidated, because our insurance market is dominated by one large player.”

In its two reports, the Petris Center found that hospital mergers led to a 10.6% increase in the prices for inpatient admission at the merging hospital in Indiana, and each additional insurer in Indiana was associated with a 3.3% decrease in insurance premiums.

Likewise, from 2010 to 2018, the share of primary care physicians who were integrated with a hospital in Indiana increased from 33% to 60%, which drove up costs slightly, too.

Tabor emphasized that hospital systems aren’t forcing hospitals or physicians to join the larger system; they’re making the choice on their own.

“In almost all cases that I’m aware of, the conversations are initiated by these community hospitals that have been meeting with their board and have realized that they can’t recruit physicians, they can’t get the negotiating rates with equipment, supplies, other things like that,” Tabor said. “Joining a system is a way to keep the hospital open, and in some cases provide more services in the community.”

Hospitals and insurance companies point the finger at each other for contributing to at least part of the price increases.

“The biggest thing that we face from the insurance side, especially in our negotiations in reimbursement rates, is the consolidation of the hospital market, and the fact that you’ve now got basically five or six big systems that seemingly on a yearly basis are gobbling up the rest of the industry,” said Marty Wood, president of the Insurance Institute of Indiana. “So their bargaining power is enhanced tremendously each year as they grow their market share.”

Meanwhile, IHA in part blames insurance companies for higher health costs, and say the industry could be more transparent by sharing what dictates how much insurance companies charge.

IHA also argues that investing in improving Hoosiers’ health, such as the large public health investment proposed by Gov. Eric Holcomb, would help reduce costs.

Here are the bills House and Senate Republican leadership are pushing to try to address the problem:

This bill would require health care providers to charge for services based on where the service is actually provided. Currently, health providers can charge more for a procedure if it’s performed at a hospital-owned clinic — as if it were being performed at a hospital — rather than an independent clinic. Drafted by Valparaiso Republican Sen. Ed Charbonneau, this bill would end that practice.

Legislators killed a similar proposal in 2020 after hundreds of health care providers gathered at the Statehouse in protest and IHA warned the consequences could be catastrophic for hospitals.

“I say this without exaggeration … It would close hospitals,” Tabor said last week. “It would force some to consolidate.”

Senate Bill 7 aims to increase competition, allowing more doctors to work where they choose in the state. The bill would prohibit noncompete clauses between physicians and their employers, which can limit doctors’ ability to continue to work in the region if they leave an employer, and also bans physicians from receiving an incentive for referring a patient to another doctor in the same network.

“In certain parts of Indiana, large hospital networks have used these noncompete clauses to control the local market for physicians, hurting competition and driving up patient costs,” said Sen. Justin Busch, the Republican from Fort Wayne who is carrying the bill.

Tabor argued that lawmakers already struck a good balance in restricting noncompetes when they passed a bill on the topic in 2020.

This bill from Charbonneau requires pharmacy benefit managers, the powerful intermediaries who negotiate drug prices between drugmakers and insurers, to pass on discounts to patients purchasing the medicine. Historically, pharmacy benefit managers have been able to keep the savings for themselves.

Wood, of the Insurance Institute of Indiana, warned the proposal could increase the cost for health care plan consumers who don’t purchase those drugs.

Under House Bill 1003, an employer would receive a tax credit for adopting a health reimbursement arrangement instead of a typical health insurance plan.

The legislation, carried by Warsaw Republican Rep. Craig Snow, also attempts to level the playing field between insurance providers, prohibiting hospitals from giving an insurance company a discount that's more than 10% less than the price given to other insurance providers. IHA warns this could take away the ability of hospitals to negotiate.

The final provision of the bill actually should provide relief to hospitals, limiting when prior authorization can be sought which may cut down on administrative costs. Those in the insurance industry say this provision could actually increase health care costs.

House Bill 1004 is arguably the most hard-hitting bill of the bunch, in that it directly penalizes hospitals.

If most nonprofit hospitals charge Hoosiers with employer-sponsored health insurance more than 260% of the Medicare reimbursement rate for services, the hospital would be financially penalized under this bill, carried by Carmel Republican Rep. Donna Schaibley. This wouldn’t apply to county-owned hospitals.

“I think it sends a really strong message that the Legislature wants to see lower prices, and I think it’s a very direct way to say, ‘You have a period of three years to lower your prices and if not, you’re going to pay for that,’” Bell said. “I think that’s bold.”

In an effort to increase competition, the bill includes a tax credit for physicians who have an ownership stake in their own practice. The legislation also appears to limit the types of physicians hospitals can employ.

Like Senate Bill 6, this bill also requires health care providers to charge for services based on where the service is actually provided; and similar to Senate Bill 7, it prohibits nonprofit hospitals from entering into physician noncompete agreements.

The IHA has numerous concerns with the bill, including the use of the Medicare reimbursement rate to determine penalties, since that rate could shift.

“We’re going to have to work with all the stakeholders,” House Speaker Todd Huston said when presenting the pair of House bills that aim to decrease health care costs. “But we’ll never lose sight of who we’re really working for, and our priorities are to lower costs for Hoosier patients and Hoosier employers.”

What’s next?

It’s still early in the process, which means the legislation could change dramatically. So far, none of the bills have been scheduled for a committee hearing yet, with roughly a month until the deadline.

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Twitter @STATEAFFAIRSIN

Facebook @STATEAFFAIRSUS

LinkedIn @STATEAFFAIRS

Header image: Members of the Indiana General Assembly clap in response to legislative changes proposed during the 2023 State of the State Address on Jan. 10, 2023, at the Indiana Statehouse. (Credit: Ronni Moore)

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

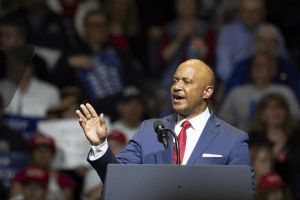

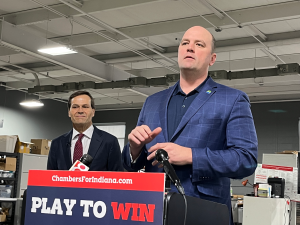

Bringing back barnstorming: Curtis Hill and his run for governor

A week after Hamas attacked Israel, Chris Just attached American and Israeli flags to the back of his Gladiator and drove to the second-annual Central Indy Jeep N’Vasion at the Johnson County Fairgrounds.

Wind blew over tents, and grim clouds approached. There, in Franklin on Oct. 14, 2023, a volunteer with former state Attorney General Curtis Hill’s gubernatorial campaign approached Just. Asked if his vote was already decided, Just said he hadn’t thought about it yet: “I know I’ll vote Republican, but I just don’t know who.” (Four years ago, Just voted for Libertarian Donald Rainwater after losing faith in Gov. Eric Holcomb.)

The volunteer brought over Hill, who introduced himself to Just. The two chatted about Jeeps, the event and topics unrelated to politics. After several minutes, Hill and Just posed for a picture in front of the Gladiator — flags prominently displayed behind them. “It gave me an introduction to who he was,” Just told State Affairs.

Presumptive voters like Just are the Hoosiers Hill’s campaign hopes to sway ahead of the May 7 primary. Polling in single digits, Hill will likely need them to prevail. In the six-candidate race, he has placed fifth in every poll conducted this year. And Hill has spent only a fraction (about $290,000) of the millions spent by other wealthy, self-funded candidates through the first three months of 2024.

In absence of the same financial treasures enjoyed by his opponents, Hill’s campaign has adopted a different approach, shunning pricey TV ads in favor of in-person events. His campaign chair since November, Jackie Horvath, said Hill, 63, flourishes in front of crowds. “Whether it be in front of thousands or in front of hundreds or tens or one-on-one, he just has that gift,” she said. Lincoln Day Dinners, for example, have been staples for the campaign, which believes enough voters will be convinced of Hill’s message to make traversing the state worth it. “You just have to be more targeted,” Horvath said.

Ahead of the primary, Hill has already earned political victories. In January, he was the first to call for the Indiana Department of Health to resume releasing terminated pregnancy reports to the public. The department had halted their release, arguing the individual reports could be reverse-engineered to identify women who have had an abortion. (The department still shares quarterly roundups with aggregate data of the individual reports.)

Hill, in a news release, said the department was “arrogantly disregarding the law” and its decision “directly contradicts the previous treatment” of the reports. He insists releasing them is the only way to ensure the state’s near-total abortion ban can be enforced.

Attorney General Todd Rokita’s office earlier this month issued an official opinion contending individual abortion reports are not medical records and can be released to the public. In a news conference announcing the opinion, Rokita credited Hill for highlighting the issue. Hill’s former opponent said voters should ask other gubernatorial candidates “where they stand on this.” During an April 23 debate, other Republican candidates said they would push for the reports to be released after Hill questioned them.

And in February, Hill implored Holcomb to deploy Indiana National Guard members to Texas, as more than a dozen other states have done. Days later, Holcomb committed to sending 50 members. He justified the decision by blaming the federal government for not properly enforcing immigration law at the border with Mexico.

Yet, despite his continued influence on Indiana politics, Hill has struggled to win over Republican voters.

“He’s kind of like that pain in your side that just won’t go away for Republicans, and I wonder if his campaign is more about spite than anything else,” said Julia Vaughn, executive director of Common Cause Indiana, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for transparent governance.

The fall

Perry Township Republicans held a Lincoln Day Dinner April 2 at The Atrium, an unassuming banquet and catering facility tucked away in a strip mall off of Thompson Road in Indianapolis. U.S. Rep. Jim Banks was scheduled to be the featured speaker, and the event drew many of the state’s most notable conservatives.

Before the dinner started, Hill told State Affairs he doesn’t believe Hoosiers want “elite candidates.” He believes there is still a place for barnstorming around the state and delivering a message in person.

In 2016, Hill was elected state attorney general. Before that, he spent 14 years as the elected prosecutor for Elkhart County, where he was born and raised. The youngest of five children, Hill earned a Bachelor of Science in marketing and a Doctor of Jurisprudence at Indiana University, where he met his wife, Teresa, according to his campaign website. They are now parents of five.

During his time as attorney general, Hill was a champion of socially conservative causes, taking to Fox News to opine on national anthem protests, crime and homelessness in San Francisco. Many considered him a “rising star” in the Republican ranks.

But Hill’s once-promising political career derailed when the Indiana Supreme Court suspended his law license for groping four women at a party marking the end of the 2018 legislative session.

The court found “by clear and convincing evidence that [Hill] committed the criminal act of battery” against three female legislative staffers — ages 23 to 26 at the time — and a Democratic legislator. Hill has maintained his innocence, saying he never inappropriately touched the women.

Prior to the court’s decision, a special prosecutor declined to file criminal charges against Hill. The women filed a civil lawsuit in July 2020, claiming Hill committed battery against them. In early April, a Marion County judge called off a jury trial for the case, which remains pending. (Attorneys representing the women did not respond to a State Affairs request for comment.)

Following the state Supreme Court’s decision, Democrats and many Republicans — including Holcomb — called for Hill’s resignation. But Hill did not resign. Instead, he fulfilled his term and lost a close 2020 Republican attorney general nomination to Rokita.

Hill has since kept a mostly low profile. His most notable foray came in 2022, when he launched an unsuccessful bid to replace the late U.S. Rep. Jackie Walorski. (He lost to U.S. Rep. Rudy Yakym, who was backed by Walorski’s family.) In 2022, Hill was also supposed to be involved in a mock trial of Dr. Anthony Fauci, the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Hill said an episode was filmed, but technical difficulties caused it to “fizzle out.”

Hill has kept busy with his namesake law practice and a consulting business, Maverick Consulting LLC. He has worked with the anti-vaccine nonprofit Children’s Health Defense and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as a consultant on “some post-pandemic matters.” And he participated in a senior fellowship at the conservative-leaning think tank Center for Urban Renewal and Education.

When he spends the weekend at home, Hill tries to make time for tennis with friends. They call themselves the Brandy Boys. Their Saturday routine: tennis, then breakfast and “a celebratory bottle of brandy that goes a long way.”

Hill told State Affairs the fallout from the court’s decision to suspend his license has been an “unfortunate chapter.” He said it was “a sign of the times when you’re a popular, particularly conservative figure, and knives come out.” Asked whether he would have done anything differently that night, Hill said he “probably would have gone home.”

His vision

On the campaign trail, Hill has advocated for a comprehensive tax plan. His proposals include cutting Indiana’s corporate income taxes and the state gas tax while also eliminating state income taxes for residents who are 18 to 35, according to his campaign website. But he says “wasteful spending” must be addressed before the tax breaks can be realized. (Hill has criticized Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch’s proposal to eliminate state income taxes for all residents.)

In addition, Hill’s campaign centers on stopping “the flood of illegal immigrants” and preserving “medical freedom.” At the COVID-19 pandemic’s zenith, Gov. Holcomb implemented a mask mandate in Indiana. Hill pounced on the decision, arguing Holcomb overstepped. “We had a government that failed us in many respects by providing misinformation, wrong information,” Hill said, pointing to guidance on mask usage changing as the pandemic progressed.

Hill maintains the damage done by government lockdowns “far exceeded the damage that was done by the virus itself, and we’re still seeing that a lot of businesses were scuttled. A lot of school kids have some learning and social behaviors that are offset because of the time that was taken away from the education process.”

Leah Wilson, executive director and co-founder of the nonprofit Stand for Health Freedom, said Hill “wasn’t tricked like others were” during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Most of the others you talk to say it was justified to cancel freedom for at least a few weeks,” she said of the other gubernatorial candidates. Because of that, Wilson’s organization endorses Hill. She said he is “not excitable, which allows him to be unwavering.”

Asked during debates about his other policies, Hill has compared the federal government to a “crack dealer” that attaches programmatic “entanglements” to its financial support of schools. If elected as Indiana’s next governor, he wants to do away with the entanglements, cut government regulations to help more child care facilities enter the market, empower locals to make their own economic development decisions, corral the Indiana Economic Development Corp. and end diversity, equity and inclusion practices in state government as well as “radical gender ideology” and “critical race theory” in classrooms.

“Objective truth is under assault on a regular basis,” Hill told State Affairs. “I think the manipulation of the justice system, the weaponization of race, the sexualization of our children call upon us to have a new administration of freedom.”

Asked about his chances of winning after several poor showings in recent polls, Hill said, “The only poll that matters is the poll on May 7.”

State Rep. Ed DeLaney, D-Indianapolis, said Hill had “managed to bring discredit to his office in an unusual and particularly terrible fashion.” In 2019, DeLaney authored a resolution urging the House to conduct an investigation of the allegations against Hill, but it wasn’t taken up.

Hill came into the gubernatorial race as a “hard-right, pro-Trump” candidate, DeLaney said, “but he hasn’t had money to send that message. And when, essentially, almost all of the candidates are sending that message, how does he distinguish himself? So, sadly for him, this distinction is the one that I pointed to: He got himself in this horrible situation.”

Horvath, Hill’s campaign chair, sees his situation differently. She described the allegations against Hill as a “he said, she said” scenario that has only been brought up sparingly on the campaign trail.

In The Atrium lobby, Hill spoke with his team, surrounded by bustling conservatives. Just, the Gladiator owner, walked through one of the facility’s entrances — he was there to support Andrew Ireland in the House District 90 race — and spotted Hill. The pair reminisced about the Jeep show. “He remembered exactly what the Jeep was; he remembered everything about it,” Just told State Affairs of his conversation with Hill.

Hill asked Just to “remember” him during the upcoming primary election, Just told State Affairs. Yet, after their April encounter, Just said he is “still kind of closed” on the candidate he plans to vote for.

“I still haven’t made up my mind yet,” Just said. But he acknowledged Hill “definitely left a mark.”

About Hill

- Age: 63

- Hometown: Elkhart

- Education: Bachelor of Science in marketing and Doctor of Jurisprudence from Indiana University

- Family: Wife, Teresa, and five children

- Job: Attorney, consultant

- Work history: Indiana’s 43rd attorney general (2017-2021), an attorney since 1988, consultant with Maverick Consulting LLC, Elkhart County prosecutor (2003-2017)

Read these related stories

- Eric Doden is running from behind but hopes his ‘bold vision’ will propel him forward

- Suzanne Crouch positions herself as a ‘different’ candidate for the voiceless

- Mike Braun on why he wants to be in politics ‘at a level of significance’

- Who is Jamie Reitenour? Indianapolis mom mobilized volunteers to make governor’s ballot

- Brad Chambers sells himself as ‘business guy’ to lead Indiana

Contact Jarred Meeks on X @jarredsmeeks or email him at [email protected].

X @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairspro

Indiana makes history with record number of Black mayors, half of them women

FORT WAYNE, Ind. — Five years ago, Gary’s Karen Freeman-Wilson was the only Black female mayor in Indiana. After she lost a third Democratic nomination to Jerome Prince, there were none.

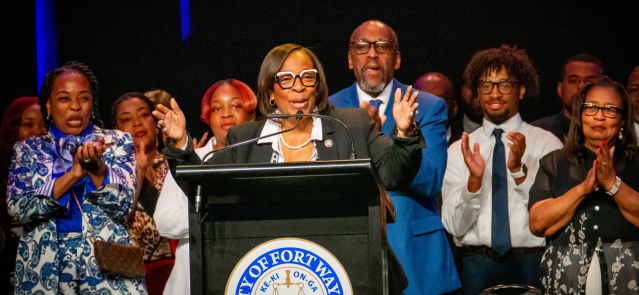

With Sharon Tucker’s Fort Wayne Democratic caucus upset win on Saturday in a seven-candidate race to succeed the late Mayor Tom Henry, Indiana now has four cities led by Black women. Each took a different path.

Democratic Vanderburgh County Councilwoman Stephanie Terry won the open seat in Evansville, the state’s third-largest city, while Democratic Councilwoman Angie Nelson Deuitch defeated Republican Michigan City Mayor Duane Parry with 60% of the vote the same day. In Lawrence, Councilwoman Deb Whitfield won the Democratic primary and then beat Republican Deputy Mayor David Hofmann after Mayor Steve Collier retired.

Tucker defeated House Minority Leader Phil GiaQuinta and Stephanie Crandall, a top aide to Mayor Henry, on the second ballot Saturday. A jubilant Tucker told the 92 precinct officials and an overflow crowd at Parkview Field: “Today you had the opportunity to make history by electing the first 5-foot-3 mayor. To be in a place where they’re fed, loved and cared for, that’s my vision for our community.”

Many saw GiaQuinta as the front-runner going into the caucus, with at-large Councilwoman Michelle Chambers in contention. But Tucker’s fiery speech before the first ballot couldn’t be denied. “I’m the only candidate who stands before you who has all those boxes checked on her résumé,” said Tucker, noting she was the only candidate to be elected at both the county and city levels. “You see, as 6th District representative, I have had the pleasure of sitting at the table with developers and investors and telling them how great our city is and encouraging them to make investments.

“I fully understand government,” she added.

The applause Tucker received quickly indicated a new order would soon be unveiled. About 15 minutes later, she led GiaQuinta 38-30 on the first ballot (Crandall had 10), with 47 needed to win. Tucker prevailed on the second ballot over GiaQuinta and Crandall after Chambers and Wayne Township Trustee Austin Knox dropped out, and two other candidates were eliminated due to a lack of votes.

In a press release, Fort Wayne Democratic Party officials said, “Today, Mayor Tucker proved that she has the energy and support of our party, and we look forward to supporting her as she works to continue moving our community forward.”

Tucker will be the second woman to serve as Fort Wayne mayor. After Mayor Win Moses resigned in 1985 following a campaign finance law conviction, Deputy Mayor Cosette Simon served for 11 days before Democratic precinct officials returned Moses to office.

Tucker replaces Mayor Henry, who was elected to a city-record fifth term last November. Henry, who announced in February that he had late-stage stomach cancer, died on March 28 at age 72.

What’s happening in Indiana is historic. Not only are four Black women leading Indiana cities, but also for the first time in the state’s history, eight Black mayors across the state are serving at the same time. The others are Mayors Eddie Melton of Gary, Anthony Copeland of East Chicago, Rod Roberson of Elkhart and Ronald Morrell Jr. of Marion. Morrell is Indiana’s first Black Republican mayor.

In February, the House unanimously passed a resolution acknowledging the historic moment.

“Whereas, It is important to acknowledge all Black leaders who are implementors of selflessness and upholders of high standards and order. The courage to lead is not easy but it is an honorable notion to take pride in; and Whereas, The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus shows its full support of the work these distinguished mayors have put forth, and it is a privilege to honor and acknowledge their names and their duty to serve the citizens of Indiana to the utmost capacity,” House Concurrent Resolution 21 states.

“I don’t know that we have ever had this many Black mayors in city halls across the state of Indiana,” Indianapolis Recorder columnist Marshawn Wolley wrote last November.

Terry told WFIE-TV after she declared victory in November: “Honestly, it’s surreal. I never believed an African American could really be in this position. The fact is our city is ready to move forward, that this city really is for everyone and that we can be inclusive.”

Lawrence Mayor Whitfield, giving her first State of the City address in February, said, “During the last year, many of you may have heard me say, ‘It’s time!’ To me, that turn of phrase has meant so many things in so many contexts. It means it’s time to bring new, forward-looking leadership to our city. It’s time to take the momentum of the past administrations and move forward to achieve our goals. And, of course, it’s time to unite our city and make sure we are connected on a deeper level than ever before.”

Mayor Terry told Evansville residents at her first State of the City address last month: “One hundred days ago, we launched a new era in Evansville. We broke two glass ceilings, swearing in the first Black mayor and the first female mayor in the city’s 212-year history. The energy, the enthusiasm, the hope that I felt that day have carried us through these first 100 days as we’ve finished assembling our team and gone right to work moving Evansville forward.”

Terry added, “I said at my inauguration that I knew I was going to be held to a higher standard, and I knew you were going to be watching. And I told you I was ready. I told you I was going to make sure Evansville is a city that works for everyone, and I knew you were going to hold me accountable for that. I knew I was going to hold myself accountable, too.”

Brian A. Howey is senior writer and columnist for Howey Politics Indiana/State Affairs. Find Howey on Facebook and X @hwypol.

X @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairspro

Brad Chambers sells himself as ‘business guy’ to lead Indiana

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is one in a series of profiles of the candidates running for Indiana governor.

Brad Chambers argues big ideas and actions are needed in the coming years to propel Indiana and its economy forward.

Chambers has already put $9.6 million of his own money toward that argument as he tries to transform himself from a successful real estate developer who was virtually unknown by the general public into the Republican nominee for governor.

The first steps for his entry into the governor’s race came during his time as Gov. Eric Holcomb’s state commerce secretary and leading the Indiana Economic Development Corp. — the agency tasked with attracting business growth to the state.

A big idea from Chambers’ time with the IEDC was the LEAP Lebanon Innovation District, a planned 9,000-acre hub for tech-related industries that has been a target of criticism from the other five Republican candidates in the May primary.

Chambers remains steadfast in defending the project as a needed asset to compete with other states for major projects and asserts Indiana needs more of that kind of leadership.

“What I bring to this race is I’m not making decisions — and LEAP is proof — I’m not making decisions on three-year election cycles because I’m not an elected official,” Chambers said during an interview with State Affairs. “I’m making decisions like a business guy — which is, ‘What’s good for Indiana?’ — no matter if I’m around to see it come to fruition or not.”

Path to business success

Chambers, 59, grew up in Indianapolis as a son of prominent businessman William Chambers, who participated in numerous civic organizations and was the finance chairman for Republican Dan Burton’s 1982 election to the first of his 15 U.S. House terms, according to the elder Chambers’ 1997 Indianapolis Star obituary.

Brad Chambers traces his business career back to a lawn mowing service he started with some friends while a Lawrence Central High School student.

He said he was using his share of the profits to pay his Indiana University tuition before one of the friends bought him out a few years later for $5,000. It became the seed money to purchase a repossessed house in Indianapolis as a rental property.

“I like to say it was divine intervention that I didn’t blow it,” Chambers said of the lawn service buyout.

That first property sparked his interest in the real estate business.

“I’m like, this is kind of fun, and so I ended up rooting around and by the time I graduated from IU, I had 31 rental units,” he said.

Those rentals were the start of Buckingham Companies, the development business Chambers founded. It now claims a portfolio of $3 billion in a variety of apartment, retail, hotel and business projects with more than 400 employees in nine states.

Buckingham’s prominent Indianapolis work includes the CityWay development, which has apartments, retail sites and the upscale Alexander hotel near Gainbridge Fieldhouse.

Chambers said he stepped away from day-to-day company leadership when Holcomb selected him in 2021 as state commerce secretary, a post he held for $1 a year before resigning last August to launch his gubernatorial campaign.

The breadth of Chambers’ business is represented in his candidate financial disclosure statement, which lists ownership of 63 properties in nine states and stakes in 279 real estate or other partnerships. He said he would keep his business interests separate from state actions if he became governor.

“Indiana is obviously important, but we’re a national company, we’re doing business all over the country,” Chambers said. “We understand the rules of the road there and our guys are running the business and they’re doing a great job.”

Road to the governor’s race

Holcomb recruited Chambers to the state commerce secretary job in 2021 after the position had been vacant for about four months.

Chambers said that about a year later, others began raising the idea of him running for governor in 2024 since Holcomb couldn’t seek reelection because of term limits.

“I never really gave it too much thought until [2023,] probably second quarter of ’23, and then started thinking about it in earnest,” Chambers said. “I’m not a politician. I’ve never run for [anything]. I didn’t know anything about it. So I had to understand it and then started doing what business guys do, which is evaluate, and it was a tough decision.”

Republican Fishers Mayor Scott Fadness said he got to know Chambers after he started leading the state’s economic development agency.

Fadness, who has been mayor of the Indianapolis suburb since 2015, said he quickly became impressed with Chambers’ willingness to talk in depth about big ideas.

Those conversations grew to include discussions about whether Chambers should run for governor, although Fadness said he largely explained the hurdles Chambers would face with his campaign.

“He could be living a very good life, doing a variety of other things,” Fadness told State Affairs. “I think he just felt compelled to run because he wants to move Indiana forward. That kind of leadership and that kind of motivation is a rarity in politics anymore, and I guess that’s what kind of made me gravitate towards him.”

Many prominent Indiana business leaders have joined in supporting the Chambers campaign. Among those making sizable contributions are Eli Lilly and Co. CEO David Ricks ($100,000), Kittle Property Group CEO Jeffrey Kittle ($100,000), Indiana Pacers owner Herbert Simon ($50,000) and retired Lilly CEO and IEDC board member John Lechleiter ($50,000).

Chambers has been willing to sink own money — $9.6 million as of mid-April — into the campaign for his message that he’s “a business guy” focused on growing the state’s economy.

“That story resonates, but it’s six and a half million people to communicate with,” Chambers said of Indiana’s voting-age population. “It takes time and it takes resources.”

Critic calls LEAP District planning ‘underhanded’

Indianapolis-based Lilly was the first company making a major commitment to the LEAP District, with a $3.7 billion research and manufacturing campus now under construction.

Chambers points to the district as a major step toward making Indiana competitive with other states for major projects. He argues that Indiana lost out on perhaps landing a $20 billion Intel microchip plant to the Columbus, Ohio, area because it didn’t have a ready-to-build site available.

Chambers’ critics argue the LEAP District is an example of “top-down leadership” at the Indiana Economic Development Corp. that disregards the concerns of local residents and officials.

Project opponent Brian Daggy, a retired Boone County farmer, said Chambers hasn’t tried to engage with those whose homes would be affected by the LEAP District transforming what is now largely farmland into manufacturing and research facilities.

Daggy and his wife bought a house in the northern part of the district as their retirement spot a few months before finding out in late 2021 about the IEDC buying up land for the project. Daggy has turned down purchase offers and helped organize the Boone County Preservation Group, of which he’s now president.

Daggy said he understands wanting to see government operate more efficiently and business-like but that the IEDC under Chambers showed a disregard for the residents’ concerns.

“He has given all indication that he knows what’s best, and that’s what he’s gonna carry forward,” Daggy said. “It causes me concern, a lot of pause, thinking about that he would run the state in that kind of a manner.”

A proposed 35-mile pipeline to transport water from a Wabash River aquifer near Lafayette to the LEAP District has drawn opposition from the Tippecanoe County area over concerns such as a loss of irrigation for farmers and worries about environmental damage from pumping out potentially tens of millions of gallons of water a day.

Residents in the Lafayette area didn’t know the pumping tests were being carried out for the proposed pipeline last year until they suddenly didn’t have water from their wells or noticed sulfur odors from their water they had never smelled before, said Sandra Alvillar, president of the group Stop the Water Steal.

Chambers, Holcomb and Republican legislative leaders have said no work on building the pipeline will go ahead unless an ongoing aquifer study shows adequate supply.

Alvillar, however, called the IEDC’s planning for the pipeline “underhanded” and said Chambers and the agency have been focused on a public relations response rather than listening to local concerns.

“If they have not been transparent up to this point, once they’re safe in their little office, it’s not going to get better,” Alvillar said.

Chambers has kept his focus on the economy

Chambers has focused his bid for governor on economic issues and running a decidedly non-Trump-like campaign. He has largely avoided hot-button culture issues, pointing in his TV ads and public remarks to former Gov. Mitch Daniels, who had a similar emphasis while in office, as a leader he would emulate.

Chambers has touted his “Play to Win” plan as aiming to boost business growth in the state through steps such as more infrastructure investment and increased support for small businesses and entrepreneurs.

“The one thing that I know touches every Hoosier, not some Hooiers, is financial security and opportunity,” Chambers said. “Fundamental to quality of life is good education and public safety, and you can’t fix those or invest in those without a growing economy. I believe when people have financial security, their health is better, their kids are better, their housing is better and overall quality of life is better. So I’m just focused on the one topic where I have had some experience.”

Chambers remains an underdog in the governor’s race, as a State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana poll in early April found U.S. Sen. Mike Braun with support from 44% of likely Republican primary voters.

Chambers, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch and Eric Doden each received about 10% support — and roughly 6 in 10 respondents were unfamiliar with Chambers despite the millions of dollars he’s spent statewide on TV ads.

Fadness, the Fishers mayor, said he believed Chambers would bring a needed sense of urgency and decisiveness to the governor’s office and hoped Chambers’ focus on the state’s economy would still catch on with voters.

“Those may not be the talking points that garner the most attention from people or get the headlines, but those are the things that are going to decide the trajectory of our state for many years to come,” Fadness said. “I think they’re vitally important. But I also am, I guess, a realist in that I understand that those aren’t always what folks spend their time and attention on in a political race.”

about Chambers

- Age: 59

- Hometown: Indianapolis

- Education: Bachelor’s degree in finance from Indiana University

- Family: Married to Carol with an adult son, Nick

- Job: CEO of real estate development firm Buckingham Companies since founding it as a college student in 1984

- Work history: Indiana secretary of commerce under Gov. Eric Holcomb, 2021-23; previously chairman of the Indiana State Fair Commission

Read these related stories

- Eric Doden is running from behind but hopes his ‘bold vision’ will propel him forward

- Suzanne Crouch positions herself as a ‘different’ candidate for the voiceless

- Mike Braun on why he wants to be in politics ‘at a level of significance’

- Who is Jamie Reitenour? Indianapolis mom mobilized volunteers to make governor’s ballot

Tom Davies is a Statehouse reporter for State Affairs Pro Indiana. Reach him at [email protected] or on X at @TomDaviesIND.

X @StateAffairsIN

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairspro

Final Republican governor debate focuses on economics, abortion

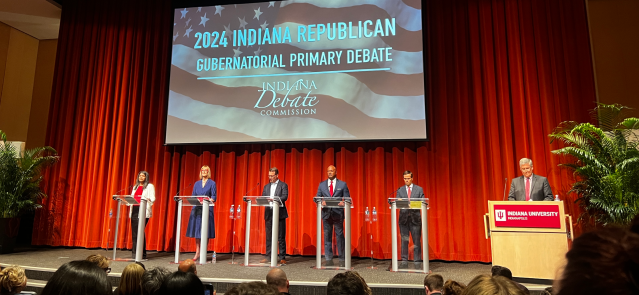

INDIANAPOLIS — Five hopefuls vying for the chance to be Indiana’s next governor took each other to task — and at times fought the questions themselves — on economic development, social issues, election integrity and more during Tuesday’s Republican gubernatorial debate hosted at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

The debate, the last of the primary cycle and sponsored by the Indiana Debate Commission, at times spiraled into revolt, as candidates disagreed with moderator Jon Schwantes’ yes-no questions on election integrity and immigration. In other moments, the candidates stuck to their various platforms on taxes, education and beyond.

Former state Secretary of Commerce Brad Chambers, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, Fort Wayne businessman Eric Doden, former state Attorney General Curtis Hill and Indianapolis mom Jamie Reitenour participated.

Sen. Mike Braun, who has thus far led the crowded field in the polls, informed the Debate Commission on Monday that he would not attend the debate. He returned to Washington, D.C., where he cast one of 19 dissenting votes against a $95 billion aid package for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan. The bill passed the Senate on a 80-19 vote.

Braun’s rivals targeted him several times in his absence, but the five candidates on stage mostly focused on one another throughout the debate. Gov. Eric Holcomb, a frequent target in previous debates, was hardly mentioned.

Schwantes, host of the WFYI-FM series “Indiana Lawmakers,” read from a slate of questions submitted in part by state voters and selected by the Debate Commission.

Election integrity

The night’s first major clash occurred during yes-no questioning on the safety and authenticity of the country’s elections.

Each candidate except Reitenour said they were confident in Indiana’s election integrity. All acknowledged the 2020 election was not stolen.

Asked if Joe Biden was the duly elected president, Hill and Reitenour pushed back, saying “anomalies” were not properly investigated.

The candidates essentially refused to answer a question asking if they would accept the 2024 election results, saying it was too hypothetical.

Agreement on abortion

Several questions were asked about abortion, though the candidates largely agreed on the issue.

The group was asked whether the state’s current abortion ban, which includes exceptions for rape, maternal health and other limited circumstances, was sufficient.

Chambers, Doden and Crouch agreed it was.

Hill called for increased enforcement of the ban, saying the state’s health department is not providing the necessary reports for terminated pregnancies.

“I brought 2,411 unborn babies from Illinois to have them buried in Indiana to establish their humanity,” Hill said, referencing a 2020 action he took as attorney general.

Reitenour did not answer the question directly, saying only that “we need to be a state that says we are for life.”

The group refused to answer when Schwantes asked if they agreed with the Indiana Supreme Court, which he said found the maternal health exception to be necessary under state law.

The candidates also agreed on in vitro fertilization, saying it should be allowed in Indiana. Some conservative states have targeted the procedure as part of the abortion debate.

Return to the IEDC

The Indiana Economic Development Corp. (IEDC), and particularly its LEAP Innovation District project seeking to build a ready-made space for business in Lebanon, Indiana, was a return topic from past debates. Chambers and Doden previously led the organization, and Chambers rose in defense of the LEAP District.

Reitenour called the project “putting a whale of a company in the middle of the desert with no water.”

Doden also directly criticized it, saying the IEDC existed only to help businesses navigate government rules.

Hill called the IEDC “a shadow government” that needed to be “reined in.”

Crouch used the question to launch into her plan to get rid of the state’s income tax.

“It’s a terrific contrast between career politicians and small thinking,” Chambers said in response to the criticisms.

Chambers goes after Crouch

Crouch was asked whether it made financial sense to cut the income tax, which brings in billions in state revenue each year.

Chambers seized on the topic.

“It’s a political talking point if ever there was one,” he said. “She has not told us how much she’s going to have to cut education, public safety, police, mental health or health care.”

Crouch doubled down, noting the income tax is already phasing down to below 3% in the coming years.

“Let’s just keep going in that direction when we have excess surplus in revenues,” she said.

Differing education approaches

A question about improving Indiana schoolchildren’s test scores led to a contrast in policy approach.

Doden and Crouch focused on school choice and workplace development.

Chambers said students require individualized learning opportunities.

Reitenour railed against critical race theory and social-emotional learning, saying kindergarten through fifth grade students need more focus on educational fundamentals.

Hill urged schools to stop taking federal money that requires certain programs, which Crouch joined in supporting.

Closing statements

Candidates were allowed to summarize their candidacy in final closing statements.

Chambers focused on his economic plan, likening his hopes for the state to his career as a businessman.

“We believe it’s time for a CEO, someone to run [the state] like a business,” Chambers said.

Hill leaned into social issues, railing against abortion and claiming “there are only two genders.”

“Don’t let politicians give you a laundry list of conservative talking points and say that’s enough,” Hill said. “Prove you can do the job.”

Doden focused on his platform talking points: restoring small towns, growing the economy and expanding zero-cost adoption.

“We have more plans in writing than everyone on this stage combined,” Doden said.

Crouch returned to her key proposal, which would eliminate the state’s income tax.

“My opponents say it’s a gimmick, but what they’re really saying is the government needs more of your money and you need less of it,” Crouch said.

Reitenour said God called her to run and cast doubt on Indiana’s conservative reputation.

“We live in a state that says it’s a red state and believes in conservative values, and yet I am trying to figure out where the conservatives are in government,” she said.

Read this related story

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

And subscribe to State Affairs so you do not miss an update.

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs