Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoHalf of Indiana’s counties are losing people. Gubernatorial candidates talk solutions.

An industrial park on the north side of Mitchell largely sits empty, awaiting new employers eager for space that's already level and connected to utilities. Mayor Nathan Jenkins said he's hoping to hear back from potential businesses in the next few months. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

- Rural Indiana has been hit hardest by population loss

- Young people are leaving in part because of a lack of child care, jobs and education opportunities

- Candidates running for governor share their visions for solutions

MITCHELL, Ind. — One of the symptoms of population decline here came in 2018. That’s when Kroger closed the city’s only full-service grocery store, soon replacing it with a Ruler Foods, a discount store with limited options.

Now residents are forced to drive 15 minutes to Paoli or Bedford if they want to visit a deli counter or buy most brand name foods.

“That one stirred people up for a while,” Mitchell Mayor Nathan Jenkins told State Affairs. “That’s just the way things are today.”

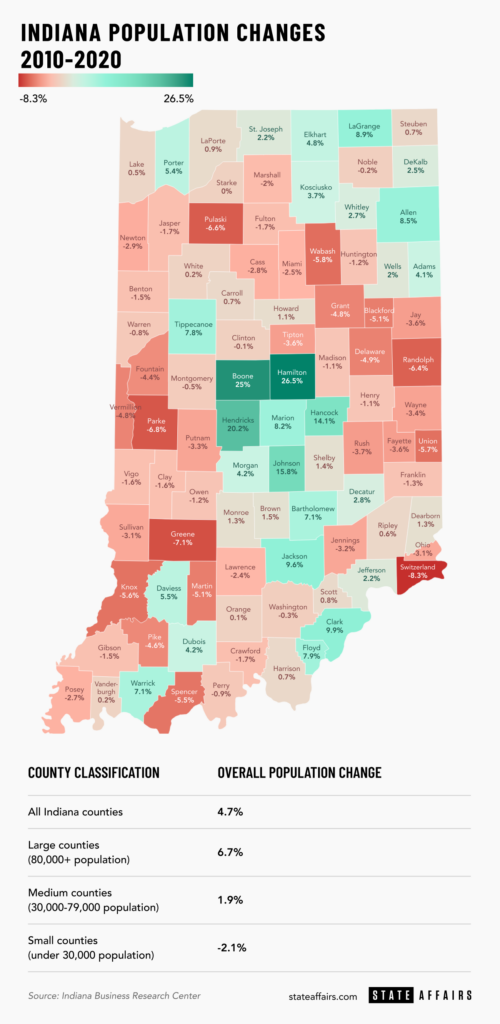

The loss of a grocery store is just one consequence of the city’s yearslong population decline. Mitchell’s population dropped nearly 10% between 2010-20, according to census data, landing at about 4,000 people. The population for Lawrence County tracked the decline, losing 2.4% during the same period.

They’re not alone. Half of Indiana counties lost population during those years, even as the state’s overall population grew. With uneven population growth across the state, the drop in residents occurred more often in Indiana’s less-populated counties. The state’s 10 smallest counties all lost population, while the 10 largest all gained population.

As part of its coverage of the 2024 election, State Affairs asked the leading candidates running for governor how they would address the slide afflicting half the state. The candidates, whose responses are included in this article, touched on education, economic development and quality of life.

Mitchell is facing a number of challenges, Jenkins said. It’s tough collecting enough taxes to fund basic infrastructure, like roads, or identifying how to help the increasing number of residents openly struggling with mental illness. In the city’s downtown core, for-sale signs adorn empty buildings.

And he’s trying to convince new businesses to commit to the industrial park where the sites are already leveled and connected to utilities but are mostly vacant. Without those employers — and the jobs they bring — young people are forced to leave town. The cycle of population decline is then renewed.

“To be truthfully honest, we have nothing to offer a graduating senior,” Jenkins said. “When they graduate, either they’re going to go off to school or they’re going to find employment, and they’re not going to find employment in Mitchell.”

Why rural areas are losing population

Rural Indiana is struggling the most.

While the state’s metro areas grew by more than 6% between 2010-20, rural counties as a whole lost 2% of their population. The number may seem small, but it belies future trouble: The population losses for people younger than 18 was closer to 8%, said Matt Kinghorn, a senior demographic analyst at the Indiana Business Research Center.

“As more and more young adults move away, maybe for school, and then look elsewhere for employment opportunities, that tends to cause a population decline in those rural areas, and if you have it going on long enough, the trend tends to compound itself,” Kinghorn said. “If those young adults move away … then the families that they will have aren’t in [those rural] communities.”

The trends aren’t unique to Indiana. Rural areas across the U.S. lost population between 2010-2020, the first decade-long rural population loss recorded in U.S. history, according to research conducted by the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy.

Rural leaders saw a slight increase in population during the pandemic, but experts warn that’s most likely an anomaly since rural communities continue to face significant headwinds.

Part of that is due simply to a lack of employers in some rural Indiana communities to attract talent.

But Michael Wilcox, assistant director and program leader for community development with Purdue Extension, pointed to quality of life and place issues as well. That includes a lack of grocery stores, child care, housing and broadband in rural communities.

Quality schools matter, too, he said, especially for rural communities hoping to win over those parents who work remotely.

In a 2017 study commissioned through Ball State University, the Indiana Chamber of Commerce sought to determine whether smaller school districts saw worse educational outcomes.

The study’s results were stark. Students in smaller districts — the study noted a 2,000 student threshold — fared worse in several categories: Scores for state standardized testing and the SAT, the pass rates for Advanced Placement classes, the list goes on.

It amounts to a “two-tiered education system” that forces families to flee smaller communities, said Kevin Brinegar, CEO of the Chamber.

To be sure, employers across Indiana are searching for answers to other problems holding back large stretches of the state, such as the lack of child care and housing stock. Those issues require policy solutions, too, Brinegar said.

“But I don’t think we’re going to achieve as much as we could or should if we don’t equalize the opportunities for students in K-12 between the larger districts and the smaller districts,” Brinegar said.

Addressing schools to help rural Indiana

Most candidates running to be the next Indiana governor are paying attention to education. Four of the six contacted by State Affairs specifically mentioned the topic as one way to reverse the population declines in rural Indiana.

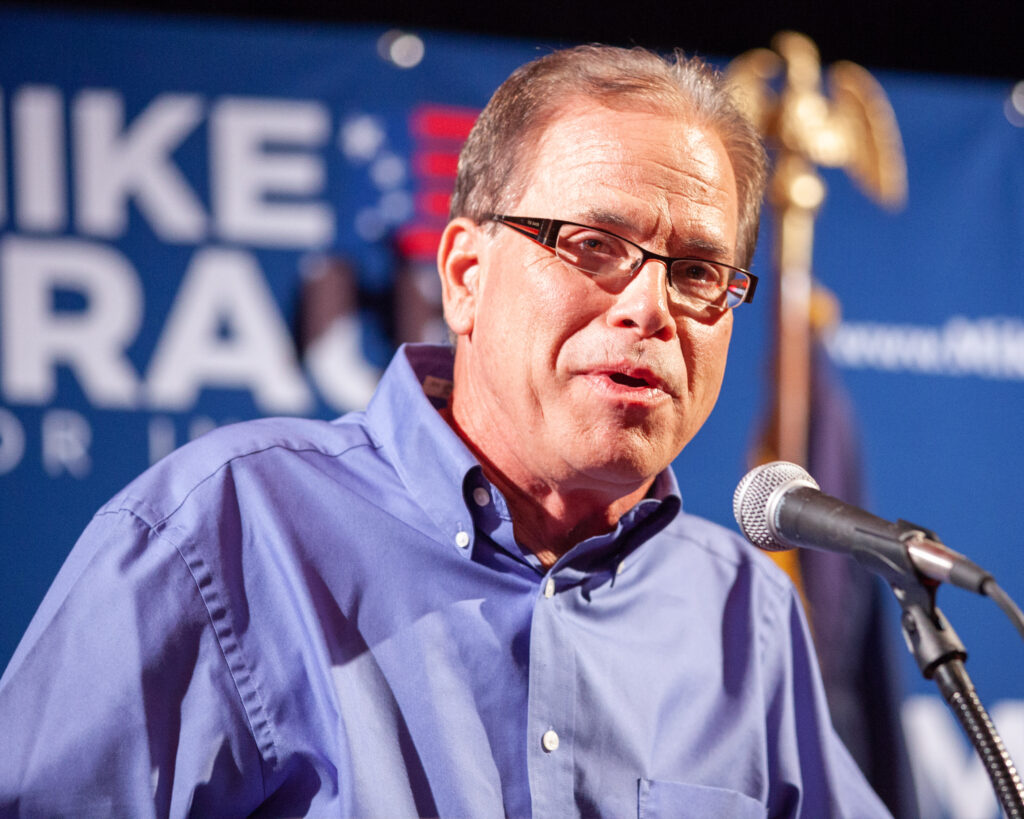

U.S. Sen. Mike Braun, a Republican, did not agree to an interview request, but in a statement said, “K-12 needs to be flexible to give rural children the chance to be a doctor or go into advanced manufacturing.”

In interviews, two of his competitors for the Republican nomination — Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch and Fort Wayne businessman Eric Doden — described specific policies they would enact if elected. So did the leading Democratic candidate, Jennifer McCormick.

McCormick, a former Republican who previously served as the state Superintendent of Public Education, is centering her campaign on education policy. While she agrees there’s a problem among rural K-12 schools, her solution doesn’t hinge on reducing the number of small public school districts.

Instead, she wants the state to reevaluate its continued expansion of school choice vouchers, which enables students from families of four making up to $220,000 per year to use state money to attend any school they want. That includes private schools. Lawmakers expanded the program during the most recent legislative session, diverting a larger chunk of K-12 funding toward vouchers.

“It’s really a subsidy for wealthier people at the expense of our rural communities,” McCormick said. “If we don’t get that school piece right, we’re never going to attract people and we’re never going to have educational attainment to the level we need it.”

She also blames rural population decline in part on blighted homes and a lack of early child care.

For Crouch, it starts with providing state-funded pre-K classes to every 4-year-old in Indiana. Right now, Indiana places income requirements on state-funded preschool and restricts which providers are eligible to accept the vouchers. The state’s laws around child care and early childhood education also need to be modernized, Crouch said, to increase the number of eligible providers while still protecting the safety of children.

Crouch said improving early childhood education would address Indiana’s workforce challenges now (because would-be workers need child care in order to re-enter the workforce) and in the future (because children with access to early education are better prepared for lifelong learning). She would like to see more housing developments in Indiana that have child care embedded into the development.

Doden, likewise, said he wants to expand education for 4-year-olds through a community-based match program. He provided a window into how it might differ from the state-funded program already in place, by comparing his not-yet released plan to other state initiatives that require larger community matches. He said it would not be a “one-size-fits-all model that balloons the state budget.” Doden also plans to repeal the state income tax for K-12 teachers, in an attempt to attract and keep more teachers in the profession.

Rural development and the economy

Rural Indiana also is falling behind economically.

While rural Indiana’s GDP grew by about 23% over a recent two-decade period, according to a 2022 study from Ball State University, that’s been outpaced by a 30% growth in urban areas. Some candidates think the Indiana Economic Development Corporation (IEDC) should be a key piece of the puzzle.

Doden has centered his campaign around redevelopment. His goal is to continue dedicating economic development dollars to regional initiatives, as well as to set aside $100 million worth of yearly grants for revitalizing rural communities with 30,000 people or less. The state would contribute 30% of the cost of redevelopment projects, while the remaining costs would be covered by local governments, federal programs and the private sector.

Doden’s plan is based on his work in Van Wert, Ohio — his mom’s hometown of roughly 11,000 people. His company Pago USA instructed local community leaders to purchase dozens of dilapidated downtown buildings and restore them. The first phase of 10 will be completed this fall and include space for businesses as well as 38 new apartments.

The plan is so integral to his campaign that he co-wrote a book on the redevelopment.

“We want to take the same program … and take it all over Indiana,” said Doden, who was president of the IEDC between 2013-15 under former Gov. Mike Pence. “The government alone can not fix a community. The private sector and the private sector leaders in that community have to have a vision for their community.”

His hope is that Indiana’s population growth rate can double.

In his statement to State Affairs, Braun said his personal experience in the small city of Jasper has prepared him for the challenge.

“As someone who grew up, raised my family, and started a business in a town that had 10,000 people in 1990 and is now 16,000 people, I know the challenges and the solutions are multi-faceted,” Braun said, adding that the IEDC should begin helping rural communities as much as it’s helped urban and suburban ones, and it should foster entrepreneurship, too.

Curtis Hill, the former state attorney general who is running for the Republican nomination, did not agree to an interview request. In a statement to State Affairs, Hill criticized the shutdowns that occurred at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It is no wonder people are having to relocate,” Hill said in the statement. “I will work with lawmakers to pass legislation prohibiting our government from closing businesses, churches and schools to protect our economy and give Hoosiers a reason to stay.”

Brad Chambers, the former IEDC head under Holcomb and the newest candidate to enter the crowded field of Republicans, did not respond to interview requests.

With more than 100,000 unfilled jobs, Indiana needs workers across the state, Crouch said. And whereas residents previously moved to find jobs, she said, businesses are now following people.

Because of that, Crouch would look for ways to shift some resources away from business attraction and into improving quality of life. She also suggested tweaking Indiana’s laws on tax-increment financing and abatement — which shift tax dollars away from local governments’ operating budget — to aid in the effort.

And to bring more resources into rural Indiana, Crouch said the state should incentivize local governments to participate in federally recognized economic development districts, which would unlock additional federal funding. Crouch also would launch a statewide council on quality of life and create a rural leadership academy, where elected officials and community leaders would receive state help with resources and training.

While much of Indiana is rural, Crouch pointed to the Ball State study that emphasized that nearly 99% of Hoosiers live within 30 miles of a metropolitan area. That creates opportunities for the rural areas.

“While we have challenges in rural Indiana, they are challenges that we can address,” Crouch said.

Communities finding success

For all the struggles of many small to midsize Indiana communities, some are finding ways to buck the trends.

Jasper, which is Braun’s hometown, is only an hour southwest from Mitchell. But the city of more than 16,000 isn’t struggling to keep up, boasting amenities usually found in metropolitan areas. The community recently opened up the 63,000-square-foot Thyen Clark-Cultural Center, which houses both the library and multiple art galleries. The sound of a violin can be heard drifting into the galleries from practice studios in the building. Less than a half mile away, there’s a riverwalk furnished with a ping pong table and horseshoe courts.

And there’s still more progress in the works. The city is redeveloping the downtown area to make it more pedestrian and festival-friendly. On an August afternoon, a painter is applying a base coat of paint to the underside of a bridge on the riverwalk, preparing for yet another mural in the city.

It’s paying off: The city grew by 11% between 2010-20.

Jasper Mayor Dean Vonderheide, who is in his fifth year as mayor, attributes the growth to the diversification of the community’s employers and their ability to rethink their approach over the years to meet the needs of changing markets. The city also spends money to develop strategic plans for the future.

“I think the city has always tried to be business friendly,” Vonderheide said. “We recognize that those manufacturers have a high investment in the area, and we wouldn’t be what we are today without them.”

A similar story is playing out in Seymour, where the population grew by 23%, driven in part by an influx of Haitian and Guatemalan immigrants. Seymour Mayor Matthew Nicholson, who is wrapping up his first term in office, likewise attributed the inflow of people to the availability of jobs. But he touted a growing system of trails and parks as well.

“We have that hometown, small town feel,” Nicholson said, “but at the same time we’re big enough to have amenities that communities twice our size have.”

As for Mitchell Mayor Nathan Jenkins, he has one piece of advice for the gubernatorial candidates.

“Don’t forget about us.”

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Contact Kaitlin Lange on Twitter @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

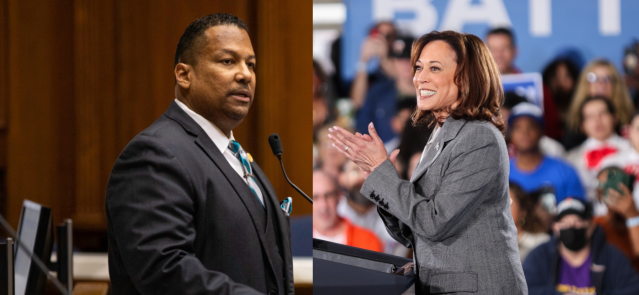

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …