Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a Demo‘I’d have fired me’; Doug Carter reflects on his career, Mike Pence, Delphi, the Indy riots and his most outspoken moment

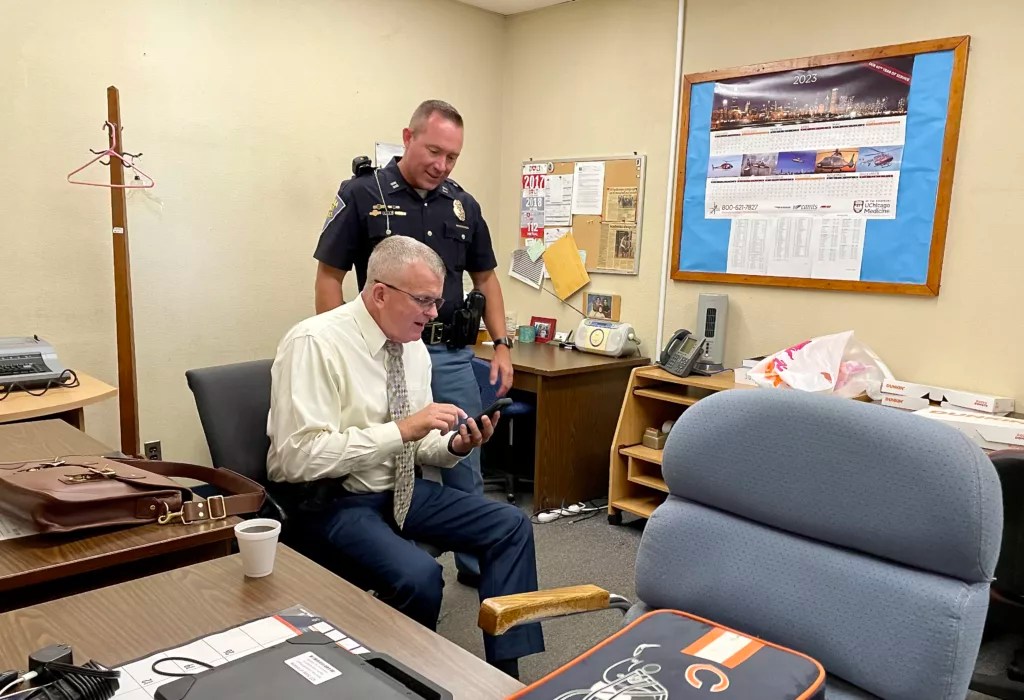

Superintendent Doug Carter exits an Indiana State Police helicopter during a trip to visit the new post in Lowell on Aug. 23, 2023. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

Last year, Doug Carter warned his wife that he expected to lose his job the next day, putting an abrupt end to his nearly 40-year law enforcement career.

It was February 2022. The Indiana State Police superintendent had walked into a state Senate committee meeting where the Republican supermajority was debating whether to remove licensing requirements to carry handguns in public. Police officers from Evansville to Fort Wayne were opposed to the bill because it would strip them of a way to more easily identify people barred from carrying weapons.

Carter, too, opposed the bill. But unlike other law enforcement officials who testified that day, Carter’s reputation preceded him as a twice-elected sheriff from the Republican Party. He also happened to be the most publicly visible member of Republican Gov. Eric Holcomb’s cabinet.

He didn’t pull any punches with his own party.

“This is the problem with the supermajority,” Carter told the senators at the time. “It stifles, prohibits, oftentimes limits public debate.”

His sharp testimony — critical of the leading lawmakers who work closely with the governor — had not been reviewed in advance by the Holcomb Administration.

“If I was the governor,” Carter told State Affairs this year, “I'd have fired me.”

So when Carter saw whose name appeared on his phone at 8:15 a.m. the day after he spoke out, he thought his career was coming to an end.

It might have been the most defining moment of Carter’s tenure as superintendent, the state’s top police officer, which is saying something. He led during times of massive upheaval in the profession: the reckonings that followed the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 and the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020.

He managed the uncertainty during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. He even stood watch in the Indiana Statehouse as people rioted against the police just blocks away in downtown Indianapolis. Decisions he made then still rattled around his brain.

In several interviews with State Affairs during the last three months, Carter opened up about those topics. Next year will almost certainly be Carter’s last as the state police superintendent and possibly as a law enforcement officer. Carter is 61. When Holcomb’s term ends in January 2025, whoever is elected governor likely will want to choose someone new to run the agency.

In his interviews, Carter described his wife’s reluctance for their family to enter the public arena; quiet moments shared with former Gov. Mike Pence; and why he believes Holcomb has been the best governor for law enforcement.

And he also talked about what haunts him: the heartbreaking stories that capture attention across the state, if not the country, such as the yearslong search to convict a killer in the Delphi murders or those long nights in hospital rooms when he joined a family as they said goodbye to a state trooper who died on duty.

Tim Horty, a respected law enforcement officer who is executive director of the Indiana Law Enforcement Academy, said Carter remains credible with police officers, the public and even policymakers because he knows the right times to fight for something.

“You can’t cry wolf every day and expect people to pay attention so you pick your battles and you decide which one that you are passionate about,” Horty said. “And then you go after it with every ounce of conviction that you have.”

In February 2022, the battle centered on the Indiana General Assembly’s decision to ignore the pleas from most police officers regarding handgun licensing requirements. The bill passed.

The phone call

After the testimony, Carter returned to his home in Cicero. He built the house himself in 1994, the carpentry trade learned from his father.

He’s not home often. When he is, he finds himself inside his workshop, cutting lumber inside the 114-year-old barn he tore down from another property and reconstructed next to the house, or chipping away at adding a 14-by-14-foot sunroom with a beam facade and a cathedral roof that his wife asked for.

She wanted a view of the backyard, but she also dreams up projects that can occupy Carter’s mind at home. It’s a form of therapy.

It was just a few steps away from that project where Carter told his wife of 30 years that the next day likely would be his last as a police superintendent. She’d watched the toll of his law enforcement career and had urged him to consider leaving multiple times — particularly when political punches hit the police profession the hardest.

Sitting on her couch last month, Carol Carter told State Affairs her suggestion if the governor wanted to fire her husband: It’s OK. Say goodbye.

“I would hate to see him go out on those terms, but you're sticking up for what you believe is right," she said. "And I always support him. So if that was the hill to die on, then so be it."

When his phone rang the next morning, Carter saw it was Earl Goode, the powerful chief of staff to former Gov. Mitch Daniels who had returned to the same position under Gov. Holcomb.

Carter considers Goode to be a father figure and mentor. He planned to resign so as to not have Goode be put in the position of firing him.

But Goode opened the conversation as he typically does: “Mr. Superintendent, how are you?”

Carter responded: “I don’t know, Earl, that’s up to you.”

Goode asked: “Did you do the right thing?”

Carter said he did.

So Goode told him: “Move on.”

And that was it. No lecture, no punishment.

‘A little bit out of concert’

Goode did not care to discuss the episode at length during an interview with State Affairs, but he acknowledged that Carter’s comments were “a little bit out of concert.”

Holcomb, Goode said, isn't one to hold a single incident against a member of his cabinet.

Goode went on to describe some of the most difficult decisions that state government leaders are forced to confront each day. Oftentimes, Goode said, there are no right answers — you just have to choose the one you think is morally right.

"Doug truly cares not only about state troopers and the state police, but he cares about Indiana," Goode said.

Holcomb ultimately signed the bill. In Indiana, there’s little incentive for a governor to veto legislation because the General Assembly can easily override his veto.

Despite the signing, Carter said his relationship with the governor did not suffer. In fact, Carter’s respect for Holcomb grew.

“I don't think there are many governors in the country that would have allowed their superintendent or colonel in the state police to put on a full frontal assault with someone of the like political party,” Carter said. “Isn't it amazing that the governor gave me the ability to get that uncomfortable?”

His relationship with some of the state senators, however, is another matter. He said he “lost a tremendous amount of respect” for some.

When the legislation made it to the full Senate, Carter took the rare step of watching from inside the chamber as lawmakers delivered their floor speeches and cast their votes.

During his comments, Sen. Aaron Freeman, R-Indianapolis, criticized Carter by name and said he found the superintendent’s prior comments about the General Assembly “objectionable.”

"I'm going to support law enforcement today," Sen. Freeman said at the time. "And by the way, I'm voting for the bill. And I hope you do, too."

Today, Carter looks back at those comments with what sounds like anger.

“The true test of who we are and what we believe comes in times of crisis and difficulty, and sometimes it's really hard to support law enforcement,” Carter said. “And he didn't.”

The two stopped talking to each other for more than a year. Then they saw each other again at a Statehouse ceremony honoring the life of the late-Sen. Jack Sandlin. Carter and Freeman hugged.

Freeman, in an interview with State Affairs, described their disagreement as a squabble more than anything else.

“We can disagree over the comments, but I know if I called him right now and I needed help, he would be the first damn person to be there," Freeman said. "And the same goes for me."

The county sheriff job and Pence rumors

Carter sees himself as a voice for all law enforcement officers in the state. His stature allows him to say what others can’t — or won’t.

Some of that he learned from his dad. When deciding how to react to a problem, Carter often thinks of something his father said: The easiest way to solve one of life's challenges is "right up the middle."

And in addition to carpentry, Carter followed his father’s example in law enforcement.

Marv Carter became a state trooper in 1962, the same year his son was born, and worked out of Dunes Park Post. The post no longer exists, but the younger Carter carries memories of his childhood at the post or sitting in his dad’s patrol car as a boy still too small to see over the dashboard.

“By the time I was a little kid, I was his partner,” Carter said. “From the late 1960s, I just got immersed into the culture of the ISP (Indiana State Police), and I just fell in love with it.”

Immediately after graduating high school in 1980, Carter left LaPorte and enrolled at Ball State University. It was too costly, though, and he left after a few semesters.

He applied to the Indiana State Police in 1983 and was not selected. He was accepted the next year, then graduated from the 42nd recruit school in November 1984 and was assigned to work in Hamilton County.

And that’s where Carter met his wife, Carol, who worked as an emergency room nurse at Riverview Hospital in Noblesville. They often talked when the young state trooper dropped off patients.

After nearly 18 years in that role, a group of Hamilton County residents approached him in 2001. Carter thought they needed to discuss a problem in the community. As it turned out, they had been eyeing him as a candidate for county sheriff.

Intrigued, Carter brought the idea to his wife, who initially told him no. Their daughter was just 6 years old, and Carol Carter was uninterested in her family becoming so public.

But she made him a promise: If he could find a group of people — “a jury of 12,” Carter said — who all agreed that it would be a good idea, then she would be all in too.

The list included the local prosecutor, the owner of a construction company, a future mayor and a county judge. They told him to run.

Carter served as sheriff from 2003-2010, a time of massive growth in the county with the construction of a new jail, administrative building, juvenile justice center and community corrections building.

After his second term as Hamilton County sheriff, Carter went to work for the architecture and engineering firm RQAW Corp. as a liaison between architects and public safety facilities. He did it for two years but, while he loved the owners and the people he worked with, he didn't find the fulfillment he gained in law enforcement.

In 2012, Carter started hearing rumors that Mike Pence, then the Republican nominee for governor, had been considering him for the role of state police superintendent.

"I just kept telling people, 'That's ridiculous,'" Carter said. "I said, ‘I've never even met Mike Pence.’”

But the rumors persisted. Carter started wondering if they were true. He talked about it with his dad. Neither had dreamed that big before.

After Pence won the general election, Carter received a phone call from an unusual number. A woman on the phone said that the governor would like to interview him. Would he be interested?

The Mitch Daniels team ‘misread him’

Pence’s transition team maintained a lengthy list of possible state police superintendents. Carter and two others rose to the top.

Like any new administration, the transition team talked to their predecessors under Gov. Mitch Daniels. Bill Smith, the man who would become Pence’s chief of staff, said some on the Daniels team recommended against Carter.

“They said, ‘He’s just stubborn, I don’t know if you’d be able to control him,’” Smith told State Affairs. “They misread him … My read on Doug was always that he had strong opinions; he might be stubborn from time to time, but it was always for a good reason — and he would then reason out what he thought. And usually he was right.”

Soon after receiving the phone call from Pence’s team, Carter found himself walking into the east doors of the Statehouse. By then, Carter had met Pence a couple times at events but never had a serious conversation with him.

It wasn’t a typical interview. They didn’t talk about leadership strategy, for example, or how to address conflict. The 50-minute conversation centered instead on Carter’s individual beliefs in faith and service. At some point, Pence moved from one part of the conference table to sit closer to Carter, almost knee to knee, as the governor-elect drew answers out of his future state police superintendent.

“It was a conversation about faith. It was a conversation about service. Selflessness. Complete, complete commitment to something other than yourself,” Carter said.

In December 2012, Pence offered the job to Carter. They waited a day to announce it publicly so Carter’s mom and dad could be there.

Pence and Carter became friends, even if they did not always see eye to eye on policy. But Carter said he always admired how Pence arrived at his decisions.

Amid the public fervor over the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, Carter walked into the Statehouse late one night and saw Pence still at his desk, looking out the window. Seeing the pain on the governor’s face, Carter sat with him for a few minutes.

“With all that was happening there and all that he was worried about,” Carter said, “as divisive as it was, he never once failed to ask about my family. And I'll never forget that about him.”

Carter’s proximity to Pence also gave him a front-row seat to some big moments. Pence, for example, invited Carter to be present when Donald Trump visited Indiana to ask the governor to become his running mate. Now, when Carter visits the Governor’s Residence, he can still envision a black Suburban pulling up and seeing Trump, a man larger than life clad in a long black coat, exit the vehicle and walk straight to Carter before entering the home.

Today, particularly after the vitriol following the former president’s attempts to have Pence overturn the results of the 2020 election, Carter worries about his friend.

“His moral compass is due north. And we live in this world where it's so easy to criticize something we don't understand. We can do it so openly, without consequence,” Carter said. “I can't even imagine what it was like to sit in the White House with Donald Trump. I can't.”

Carter knew the date that the Secret Service detail would stop protecting Pence, who was out of state at the time. Carter texted him to offer to send a trooper to stop by his Central Indiana house ahead of Pence’s return home.

But it was a Sunday, so Carter decided to do it himself. Soon, Pence arrived in a Honda Accord. He picked up a basketball near his driveway while the two talked like old friends.

“I'll do whatever I can do to help him or support him and protect him,” Carter told State Affairs. “Mike Pence changed my life forever and I'll never abandon him.”

Holcomb, the public safety governor

When Holcomb became governor, he asked Carter to remain the head of state police. And over his two terms, Holcomb has made sure his law enforcement agency saw upgrades across the state, spending tens of millions of dollars to build new state police posts in Fort Wayne, Lowell and Evansville.

The new facilities are needed. In Lowell, for example, the existing crime lab is a relic. One example: Erica Gilbert, a firearms forensic analyst, must walk through a men’s bathroom off of the maintenance garage to access the equipment where she analyzes firearms. And if the rest of the crime lab looks like the set of a 1970s sitcom, then the garage men’s bathroom looks like a 1970s truck stop — with a powerful odor to match.

That won’t be the case in Lowell’s new lab. And when Gilbert needs to compare ballistic evidence against a national database, she will no longer need to make the two-hour drive to Indianapolis to do it.

Holcomb also pushed for major renovations at the state’s training academy, cycled out older patrol cars more quickly and acquired two new police helicopters. And in his budget during the last legislative session, Holcomb baked in pay raises for state police.

The governor’s support stems from a conversation during his first term: He wanted to know what the state police needed. Carter handed him a detailed list of things that had been piling up. Ever since, Holcomb has been steadily marking off every item.

“Gov. Holcomb has done more for public safety in seven years than any governor in our history. And I'm very proud of that. I'm very proud of him,” Carter said. “I know I can pick up the phone right now and I can call Eric Holcomb and I can be in front of him within 15 minutes if he's here, no matter what.”

‘The view was like a war zone’

But Holcomb and Carter were tested three years ago.

Sometimes at night, Carter likes to wander from his office next door and into the Indiana Statehouse. He walks to the third floor behind the House Chamber, where there's a window with a view of Monument Circle.

That’s where he stood on Friday, May 29, 2020, when his vision grew clouded with tear gas deployed by the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department. Riots overtook portions of downtown following the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minnesota and the Indianapolis police shooting of Dreasjon Reed.

“The view was like a war zone. It wasn't a view of peace and stability and power and hundreds of years of people fighting for democracy and freedom and free speech,” Carter said. “What I smelled was tear gas and fire and the sound and smell of squealing tires and hate and vulgar language and urine being thrown and rocks being thrown … And I just kept thinking to myself, ‘Not in our country. Not here.’”

Riots occurred both Friday and Saturday nights as police struggled to contain the violence. Rioters set buildings on fire, broke windows, looted shops and vandalized monuments. And there was gunfire — so much gunfire — in parts of downtown lacking a police presence. Two people were killed.

Carter regrets how he reacted to those riots.

Instead of stationing about 100 state troopers downtown, he wishes he would have ordered 500. And whereas many crimes were ignored those nights, Carter said police should have arrested everybody caught committing a crime.

“And it would have been really, really ugly,” Carter said. “I acknowledge that.”

Just how ugly is hard to imagine. But what’s happened since, Carter said, is more unacceptable.

Violent crime surged in urban areas, including Indianapolis, following the demonstrations and riots across the country. Carter acknowledges that the COVID-19 pandemic played a role, but he thinks the lack of a strong police response to lawlessness played a larger one.

And, just as important, he thinks that cities across the country have never healed from the wounds opened during those nights.

That isn’t to say Carter wants to puff his chest and ignore some of the uncomfortable truths in policing today. To Carter, some things that officers love are the very things that create separation with the people they’re serving.

“I think our culture needs a redo. I believe that,” Carter said. “I've said to people, if you've not been a police officer since May of 2020, you have no idea what it's like today no matter how many years you served.”

Trooper appearances and body cameras

Carter has been implementing other changes in his agency, beginning with appearances.

He is opposed to anything resembling the militarization of police. He doesn’t want troopers to even wear aviator sunglasses. And as far back as 2013, he ruffled some feathers when he banned the use of window tinting on patrol vehicles, which he viewed as an unnecessary barrier between others sharing the roadways with officers.

“That was the most unpopular decision I made in 11 years,” Carter said. “But I'm standing by it. I want our citizens to engage with us.”

Initially, he opposed the addition of body cameras on his officers. He brushed them off as political grandstanding, something police departments accepted only because every other department had been moving in that direction. And more, he considered them to be a threat, yet another evolution that had the potential to reduce the power of an officer’s word in the courtroom.

“It seemed like we were going into this place where if it wasn't recorded it didn't happen, no matter what you say,” Carter said. “I was not going to accept that we're willing to die for someone who hates who we are, but a court's not going to listen to us after we've sworn under penalty of perjury that what we're going to say is the truth.”

Then Holcomb announced the agency would require officers to begin wearing body cameras.

“They're kicking and dragging, pulling me along, but I know everybody works for somebody. And when the governor said we're going to do this, I was all in,” Carter said. “And the things that we have learned made me realize I was so wrong for so long.”

Now he considers body cameras to be the biggest innovation in his career, even beyond stun guns. But even as he has accepted — and championed — some reforms in policing, he remains opposed to others.

For example, Carter has used his authority on the state’s Law Enforcement Training Board to push back against some of the police reforms implemented by Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett and city police leadership.

And while Carter is supportive of civilian reviews of police actions, he stands firmly against any efforts to provide them with the authority to enact police policy.

“If we're going to take policy advice from a person that's never had a physical encounter with another human being and make it rule? Shame on us,” Carter said. “I know what it's like to take a human life. I know what it's like to have to fight for my life. And that changes everything.”

Fighting for his life

It was along State Road 9, just south of State Road 67, where a 22-year-old Carter saw his first dead body. A head-on crash killed three people.

“You never forget the smell. You never forget the feeling. You never forget the glass,” Carter said.

Nor does he forget the first time he used deadly force.

It was February 1996. Carter, as a state trooper, was pursuing a man wanted by homicide detectives. By the end of the lengthy chase, an Indianapolis police officer and Carter pinned the suspect’s car next to a tree. Then the man leaned down near his seat and raised a handgun.

The Indianapolis officer shot him. Carter screamed for the man to drop his weapon. Then the man turned toward Carter, so he fired a round. It pierced the man’s shoulder, entered his chest and split into his throat.

He survived, Carter said, but his quality of life suffered.

“My daughter was one at the time,” Carter said, “and kids change everything — how you act, how you drive, how reckless you are, how far you're going to push things. And I remember that gun looked like a bazooka to me.”

Now, he also thinks about the three troopers who died during his tenure. In 2019, 27-year-old Trooper Peter "Bo" Stephan died in a crash. And then this year, Master Trooper James Bailey, 50, and Trooper Aaron Smith, 33, were killed after being struck by fleeing drivers.

Carter’s wife joined him in the hospital each time. Those moments in the hospital rooms will be the ones that families remember, and that’s why Carter had to be there. He didn’t speak much, because what was there to say? But he stood with the families.

Just like with all crime victims and families, Carter tried to bury his emotions because he didn’t want to burden the families or add additional stress.

But the emotions burst through later.

“I'm not ashamed to say that I can close my eyes and cry like a little boy when I think about what my eyes have seen. I'm not going to hide from that,” Carter said. “I'm an emotional guy. I'm unapologetic.”

A ‘man of his word’ about Delphi

The deaths of two girls in Delphi, Indiana, have hit Carter particularly hard.

Carter remembers when the girls — Abigail Williams and Liberty German — went missing one day in 2017. The next day, a state trooper called him to deliver the bad news. Authorities found their bodies.

“I don't know specifically why this affected me so personally because I've seen so much death and dying in my career,” Carter said. “The Delphi community is just the epitome of our way of life: A rural community of wonderful, wonderful people. A place where you can go and walk down Main Street and most people say hello to you.”

Their deaths shocked the quiet community and captivated a national audience. Carter appeared on the “Dr. Phil” television show and sat for an interview with journalist Megyn Kelly. Viewers remained glued to the case for years as investigators sifted through 85,000 tips submitted to state police. Part of the intrigue came from the evidence released by police as they pursued the killer — a short amount of video footage captured on one of the girl's phones of a man.

Rumors about the case seemed constant. One day a weapon was supposedly found, another day an arrest was imminent, and so forth. Angela Ganote, a news anchor who has worked at Fox59 in Indianapolis for more than 20 years, remembers picking up the phone and asking Carter directly about one of those rumors early in the case.

Carter told her: “When we make an arrest in this case, you have my word that I will personally call you.”

While their roles were in conflict — Carter’s is to conceal as much as possible, and Ganote’s is to uncover as much as she can — they shared a common belief that the girls’ families did not deserve to see inaccurate or sensational news coverage.

“In my opinion, he’s one of the most trustworthy people,” Ganote told State Affairs. “I know that he’s being honest with me, and he knows that he can trust me.”

At one point, nearly 100 detectives were working the Delphi case. Troopers canceled vacations to stay on the case.

Asked whether he ever had doubts that they would make an arrest, Carter answered quickly: “No way. Not once. Not once. Not once. You know, before my dad died, he made me promise him not to become cynical like he was. And before my dad died I told him, 'Dad, I'm not; but I'm fighting it. I'm really fighting it.'”

Carter also made this promise to himself: “I am not going to let evil win. I’m just not.”

In October 2022, Carter and his wife were in a hotel room in Barcelona, Spain, when he received a phone call from the Carroll County prosecutor. An arrest warrant would be ready by the time Carter returned to Indiana.

Carter is reluctant to share too many details because the criminal case is open and the judge has issued a gag order. But one thing Carter has pledged is to be present for the trial — no matter that it’s set to happen next year after Carter’s retirement from the state police.

“As long as I’m still breathing, I’ll be there,” Carter said.

In October 2022, Ganote had just finished anchoring a news broadcast when she saw her co-workers swarming the newsroom. She learned that police had arrested a suspect in the Delphi murders.

Then she looked down at her phone and saw she had a missed call.

“You betcha, it was Carter. And I called him back and he said, ‘We got him,’” Ganote said. “He promised years ago to call. And he’s a man of his word.”

What comes next

Asked if Carter would retire when Holcomb’s term ends, the longest-serving state police superintendent didn’t answer definitively. He knows the next governor will want someone new in his office, but Carter hopes to help with the transition.

“Yeah, I'm not a retirement kind of guy. So I don't know what's next for me. I'm leaving those options open,” Carter said. “I've got one more thing, and we'll see what that one more thing is.”

Maybe it will be in the construction industry. He’s not sure if his body is up for the demands of it, but he’s willing to try.

Yes, he learned how to become a public servant from his father, but it’s the carpentry skill that brings him happiness and provides him therapy. So when he’s spending hours in his workshop, sawing lumber in the barn he reconstructed or hanging a beam in the sun room he built, he thinks of his father, who died May 21, 2018.

“God, I miss my dad,” Carter said. “There's no day that goes by that I'm not grateful that he taught me that trade. 'You'll always have a job.' That's what he always used to say to me."

Just like his dad did for him, Carter has worked hard to be a role model for his daughter. Like how he always regretted not receiving a bachelor’s degree all those years ago, so he earned it later in life — in 2007 — at Indiana Wesleyan University. He wanted to send a message to his daughter, who was 12 at the time.

She’s 28 now, and she has a master’s degree. She also has become a police officer and carries on the family tradition. And that’s a legacy Carter can hold dear.

Contact Ryan Martin on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

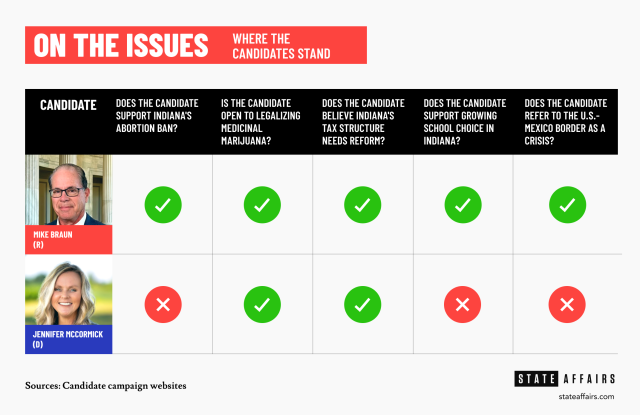

How McCormick, Braun view abortion, taxes and other key issues

A Democrat-turned-Republican and Republican-turned-Democrat will soon face off in the race to become Indiana’s next governor.

Sen. Mike Braun, who voted as a Democrat prior to 2012, captured the Republican nomination in Tuesday’s primary. Jennifer McCormick, formerly a Republican Superintendent of Public Instruction, will represent the Democrats.

Voters will decide the state’s next chief executive in November.

A State Affairs analysis of the candidates’ campaign platforms and public statements found key differences — and a few similarities — in their planned approaches to a variety of issues impacting Hoosier voters.

Here is how they match up.

Abortion

Braun: As a senator, Braun has long supported abortion restrictions.

In 2020, he called for the Supreme Court to re-examine Roe v. Wade.

In 2023, he proposed federal legislation that would have required parental notification before any unemancipated minor could seek an abortion. He said at the time: “Hoosiers put their trust in me to stand up for the unborn, and that’s what I’ve been proud to do every day in the Senate.”

He has since signaled support for the state’s abortion ban. His platform reads: “State lawmakers must work to ensure the gains we have made to protect life are secured and strengthened.”

McCormick: In a Tuesday interview with State Affairs, McCormick said her candidacy represented a referendum on reproductive rights.

“I’m going to fight to restore those rights under any authority I can, working in a bipartisan fashion, using our committees, board and our agencies. I also know, too, what everybody’s fear is: that they’re [Republicans] not going to restore those rights and will take [restrictions] further.”

From her platform: “Indiana’s Republican-led extreme abortion ban has taken away the right of women to make deeply personal decisions regarding their own health care.”

Marijuana

Braun: At a March 26 Republican primary debate, Braun suggested an openness to legalizing medicinal marijuana.

“It’s gonna hit all of us. I’m gonna listen to law enforcement — they have to put up with the brunt of it,” he said. “Medical marijuana is where I think the case is best made that maybe something needs to change. But I’ll take my cue from law enforcement there as well. … I hear a lot of input where [medical marijuana is] helpful, and I think that you need to listen and see what makes sense.”

McCormick: The Democrat’s platform also addresses medical marijuana legalization, while speculating on possible recreational use.

“We will fight for the legalization of medical marijuana as a source of state revenue established on a well-regulated marketplace and monitored by a Cannabis Task Force in order to study the issues, opportunities and potential obstructions associated with recreational marijuana legalization.”

McCormick said she would also support expunging low-level marijuana-related convictions.

Taxes

Braun: At a March 19 National Federation of Independent Business forum, Braun said the state’s property tax system “went out of whack because it couldn’t respond to inflation like we’ve never seen before.”

“The way you finance any lower taxes would be to bank on the government being run more efficiently,” he said.

His platform also calls for government spending cuts to finance lower taxes: “Reducing the size of government is the key to cutting taxes, and Mike Braun will work through every state agency to find ways to save money while delivering high-quality services to taxpayers.”

McCormick: McCormick also spoke about taxes at the March 19 forum.

“I agree with a revamp of our taxing system,” she said. “But also it’s about not just how we’re getting our revenue, it’s about our expenditures. Yes, we need to fix our gas tax. Yes, we need to look at the income tax. But here’s the thing: There are hidden taxes we’re not having a conversation about.”

Her platform also references the possibility of combining state agencies as a way to save money.

Education

Braun: In his platform, Braun supports broadening school choice and parental rights.

“As a former school board member, Mike Braun knows parents are the primary stakeholders in their children’s education and every family, regardless of income or zip code, should be able to enroll in a school of their choice and pursue a curriculum that prepares them for a career, college or the military,” the platform reads.

Braun also pledged to ensure critical race theory and discussions about gender are banned in public schools.

McCormick: Education is one of McCormick’s primary issues, according to her platform.

She calls for the elimination of statewide testing, increased early childhood reading and child care options and a minimum base salary of $60,000 for all K-12 teachers.

McCormick also addresses the state’s school choice movement.

“We will call for a pause in the expansion of school privatization efforts while requiring fiscal and academic accountability and transparency for all of Indiana schools that receive public tax dollars,” her platform reads.

U.S.-Mexico border

Braun: Braun’s television ads have touched on border security, and his platform calls for increased focus on the area.

“Joe Biden and the left have created a humanitarian and national security crisis on our southern border,” the platform reads. “As governor, Mike will continue to support and enact the America First policies that were working. Otherwise, every town will become a border town.”

McCormick: McCormick’s border-related plans are more focused on facilitating legal immigration.

“We will work with local, state and federal officials in supporting an immigrant system that creates a safe, timely, orderly and humane pathway for those seeking legal immigration while keeping our communities and those responsible for border security safe,” her platform reads.

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

Spartz, Shreve, Stutzman win Republican congressional primaries

A central Indiana congresswoman successfully fought off eight primary challengers, while crowded races for three other Republican-leaning congressional districts began to clear in Tuesday’s primary election. And in northeastern Indiana, a former congressman held on in a tight race as he seeks to return to Congress. All of the state’s nine U.S. House of Representatives …

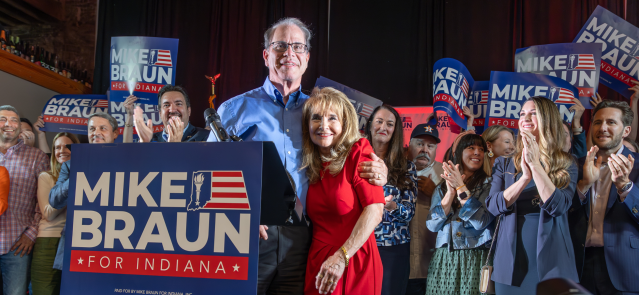

Mike Braun wins the Indiana Republican nomination for governor

U.S. Sen. Mike Braun was declared the winner of the Republican gubernatorial nomination shortly after polls in Indiana’s Central Time Zone closed. With 98% of votes counted as of Wednesday morning, Braun had 39.6%, followed by Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch with 21.8%, Brad Chambers with 17.5%, Eric Doden with 11.9 %, Jamie Reitenour with 4.8% …

Here’s how to vote in Indiana’s primary election

Thousands of Hoosier voters will head to the polls Tuesday, May 7, for Indiana’s primary election. This year’s ballot includes a competitive contest for governor, as well as dozens of state and federal legislative races and a few school referenda. The primary will decide which candidates will represent their respective parties in the Nov. 5 …