Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIndiana has hundreds of thousands of lead water pipes. Will this legislation be enough?

There are an estimated 265,000 lead service lines in Indiana. (Credit: Indiana American Water/Facebook)

When Ray Rivera Baez purchased his South Bend home in 2019, he knew he had a fixer-upper. The 32-year-old poured tens of thousands into renovating his house built in the 1950s, tearing out some of the piping in one of the bathrooms and the kitchen.

But he didn’t touch the pipes that bring water from the city’s water main to his house, pipes that, simply due to the age of his home, likely are made of lead. Since moving to South Bend, he’s stopped drinking tap water.

He’s concerned about the health implications of living in his home, but he’s already invested so much.

“I don’t have any children yet, but what if I want to raise a family there?” Rivera Baez asked. “What is that going to do for the health of my family?”

Rivera Baez’s concerns aren’t specific to South Bend residents. Indiana is projected to have a higher percentage of what are called lead service lines than at least 37 other states.

At least 1 in 10 of Indiana’s 1.9 million service lines contain lead, according to Indiana Department of Environmental Management statistics. But the issue could be more widespread: The state doesn’t know what material an additional 680,000 service lines are made of.

Those Hoosiers could routinely be exposed to extremely small levels of lead throughout their water. At worst, lead pipes are a lurking risk that could lead to a health crisis like the one seen in Flint, Michigan, in 2016, if there are changes to water chemistry or other disruptions to the pipes.

Lawmakers want to help utilities replace lead service lines more quickly by pushing Senate Bill 5, which would enable utility companies to remove customers’ lead service lines when property owners, oftentimes landlords, are unresponsive.

The goal is to allow water companies to more easily meet a proposed federal rule requiring lead service lines to be replaced within a decade. That rule would be beneficial for Hoosiers’ health, but many in the industry argue the costly ask is just not attainable, even with the added help from the General Assembly.

The bill already unanimously passed the Senate and is advancing through the House.

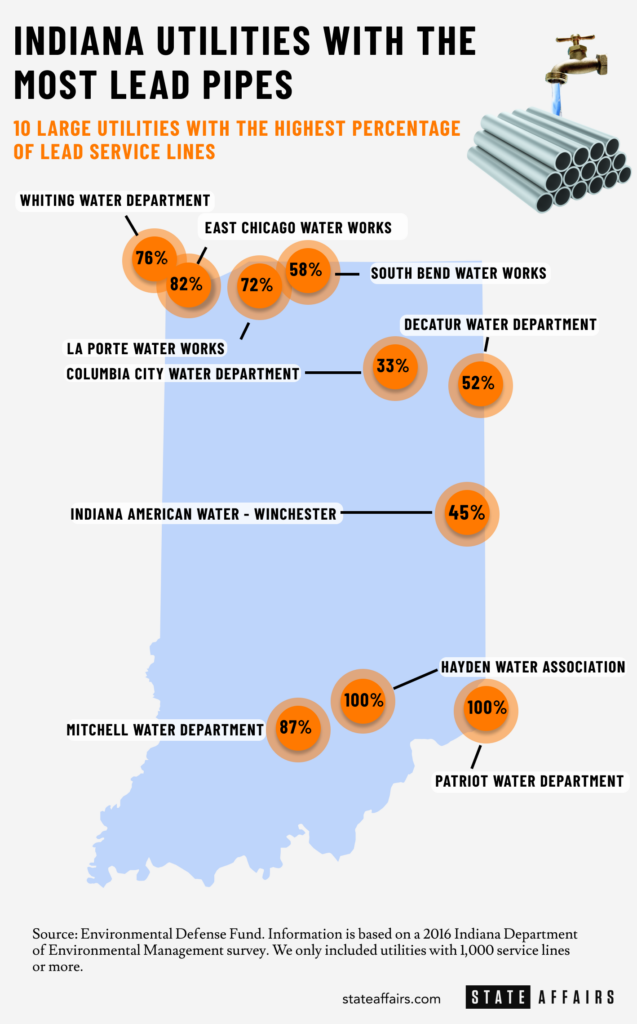

Where lead service lines are located

Typically, those lead service lines are in older neighborhoods where more people of color and lower-income Hoosiers live at higher rates. In 2016, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management surveyed the state’s utilities to see how widespread the problem was.

Hayden and Patriot, smaller communities in southern Indiana, estimated all of their service lines contained lead. In East Chicago, a city with a population that’s majority Hispanic or Black, 4 out of 5 of the service lines likely contained lead. (The rest were unknown.) And in South Bend where Rivera Baez lives, more than half the service lines likely contained lead. Some of those pipes may have been replaced since 2016.

It’s possible to guess which homes have lead service lines. The Environmental Protection Agency banned the installation of lead pipes in 1986, meaning older homes could still have lead service lines.

Still, it’s tedious guesswork.

“It’s a big undertaking,” said Gabriel Filippelli, director of the Center for Urban Health at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. “They have to tear up streets to get to the lines, and if they guessed wrong, they’ve torn up a street that doesn’t actually have lead service lines, which is a bummer.”

Utility companies stopped using lead service lines in the Indianapolis area before 1950, but some 20,000 lead service lines are still in use. That affects places like the Martindale Brightwood area on the near northeast side of Indianapolis, a community where leaders say residents have consistently felt overlooked when it comes to infrastructure investments. It’s slated to get its lead service lines replaced in the near future.

The majority of the population of the three Census tracts that Citizens Energy Group is targeting in the Martindale-Brightwood area is Black, with a higher poverty rate than the rest of Indianapolis.

“To me this is a justice issue,” said Sen. Andra Hunley, a Democrat who represents a portion of the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood. “We know that this is a health risk now, so we should have our foot on the gas and work to change as many lines as possible as early as possible.”

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, lead can be harmful even at low levels. It can cause learning disabilities that affect reading comprehension in children or cause them to act out more in school, both concerns as Indiana seeks to boost third grade reading scores.

“There really are no therapeutic interventions that currently exist to help combat lead levels that are already in the blood, and so that’s why prevention is really what is so paramount,” Dr. Jeremy Mescher, a pediatrician at Southern Indiana Physicians Riley Physicians Pediatrics, shared during testimony.

According to a study from the Natural Resources Defense Council, Indiana could save $24.8 billion worth of health care costs over the next 35 years by removing every lead pipe.

Lisa Welch, a spokeswoman for the Indiana Health Department, said the primary source of lead exposure is usually dust, paint or soil, but lead in water can be a much larger concern for babies who rely on formula using tap water.

Plus, oftentimes the same low-income households that face those other environmental hazards also have lead pipes, according to Denise Abdul-Rahman, chair of the Indiana State Conference of the NAACP Environmental Climate Justice program. That can compound the problem.

“Everyone should have the right to clean water,” Abdul-Rahman said. “But then you have basically multiple impacts in lower-income households, like lead-chipped paint, the soil contaminants, living in a brownfield area, so multiple health impacts.”

Wealthier Hoosiers living in older homes are also more likely to have the resources to remove the lead pipes without waiting for the utility companies to focus on their neighborhood, while those on fixed or smaller budgets do not.

What Senate Bill 5 will do

One of the problems utilities face as they try to replace lead service lines is unresponsive, sometimes out-of-state landlords. Because part of lead service lines are technically owned by property owners and on their property, utilities need their permission to replace that part of the pipe.

When a landlord doesn’t respond, utilities can’t do the work, extending the process to replace pipes and adding unnecessary costs to an already pricey endeavor. Plus, renters who would gladly let a utility operator on the property are stuck dealing with the consequences of lead pipes at no fault of their own.

Some of these same parts of the state that have old houses with lead pipes are rental-heavy. In the portions of the Martindale-Brightwood area that Citizens is targeting, for example, more than 60% are renters. That’s higher than the rate in the rest of Marion County.

“When a utility approaches a neighborhood for a lead service line replacement program, it is imperative that we get access to as many homes as possible to avoid remobilization,” Bridget O’Connor, senior manager of government and external affairs at Citizens Energy Group, said during a committee hearing. “Remobilization to an area to address homes that the utility was not able to access originally will add unnecessary costs to and delay overall program implementation.”

Senate Bill 5 would enable utility companies to replace lead service lines when property owners of homes and duplexes are unresponsive, as long as the replacement plan has been approved by the state regulatory body, the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission.

Meanwhile, if the owner of an apartment complex doesn’t respond, the cost to replace the lead service lines falls on them.

The bill would also allow a utility to disconnect water service if it is prevented from accessing properties, a measure that concerned some members of the House utilities committee despite broad bipartisan support overall.

Rep. Matt Pierce, D-Bloomington, said he understood that cutting off someone’s water might indirectly encourage a landlord to give a utility company access to the property, but his concern was for renters.

“Eventually you would get some leverage,” Pierce said, “but you’ve got some pain inflicted on innocent third parties in that process.”

Is SB 5 enough?

Bill author Sen. Eric Koch, R-Bedford, said he thinks Indiana should aim to replace its lead service lines more quickly than the 10-year window the proposed federal rule would require. But even finishing the job in 10 years is a lofty goal.

So far, only three utility companies in Indiana have had their plans approved by the commission. But those three provide a window into how challenging replacing all lead service pipes in Indiana will be, especially in a state that is sometimes reluctant to shell out additional funding.

In 2018, Indiana American Water estimated it serviced about 50,000 lead service lines across the state. The company replaced or retired half of those over the course of five years. On average, replacing an entire service line cost the company about $8,100. Retiring a line or replacing only half was cheaper.

If every Indiana utility company replaced all estimated service lines at that price over the next 10 years before inflation, it would cost more than $2 billion — well over the $65 million the federal government will give Indiana this year to provide reduced or zero-interest loans to replace these lead service lines.

“When you’re dealing with something where you don’t actually know the extent of the problem with certainty,” the Center for Urban Health’s Filippelli said, “you don’t know how much it’s going to cost to clean it up necessarily.”

Likewise, the proposal approved in 2022 for Citizens Energy Group, which provides water only for the Indianapolis area, was initially intended to be a 33-year plan to replace the company’s estimated 55,000-75,000 lead service lines to limit rate increases for water users. O’Connor said the estimated cost to replace all of Citizens’ lines is $500 million.

Brian Rockensuess, commissioner of the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, is skeptical that 10 years is enough time, amid concerns that replacement parts will skyrocket as demand goes up.

“The idea of replacing these lines is a good idea. The problem is the timeframe,” Rockensuess said. “It is such a short time, and the amount of service lines that we have, plus the amount of money this is going to cost, is going to be something that I don’t think any utility in the country is going to be able to afford to do.”

And if utilities can’t afford it, water users will face rate increases.

The proposed federal rule isn’t final yet and could still change.

What to do if you suspect you have lead service lines

Usually, you can contact your water utility company and request a test to see if your pipes contain lead.

If the pipes are made of lead, Filippelli said a simple water filter, such as a Brita, will suffice if you plan to drink or cook with the water. Lead can’t be boiled out. Bathing in the water is still fine.

“Lead, for how dangerous it is, is actually pretty easy to deal with once you know where it is,” Filippelli said. “It’s only dangerous because we don’t know.”

In some areas, like in Indianapolis, a property owner not in a prioritized area for replacement can request that a utility replace the lead service lines, but the property owner would have to pay to replace the cost of the service line on their own property.

What’s next

Senate Bill 5 is scheduled for a hearing in House Ways and Means today. If it passes that committee, it could be up for a vote as early as next week.

Update: The legislation for this plan, Senate Bill 5, won approval from the General Assembly, and Gov. Eric Holcomb signed it into law March 11.

Contact Kaitlin Lange on X @kaitlin_lange or email her at [email protected].

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Read this story for free.

Create AccountRead this story for free

By submitting your information, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy.

Here’s how to vote in Indiana’s primary election

Thousands of Hoosier voters will head to the polls Tuesday, May 7, for Indiana’s primary election. This year’s ballot includes a competitive contest for governor, as well as dozens of state and federal legislative races and a few school referenda. The primary will decide which candidates will represent their respective parties in the Nov. 5 …

$15B in 72 hours: ‘Our economy is on fire,’ says Commerce chief

A banner week for investment within Indiana has capped off the state’s biggest financial quarter in recent history, as three major companies agreed to deals estimated to bring in billions of dollars. The state has long advertised itself as business-friendly, and its chief executive appeared thrilled by the week’s news. “This is about $15 billion …

6 races to watch in the Indiana primary election

The first openly competitive contest for the Republican gubernatorial nomination in a generation will end with Tuesday’s primary election, as will crowded races for several open congressional seats.

The primary won’t officially decide any political race — only the Nov. 5 general election can do that. But Republicans hold major advantages in statewide and many district-level contests, and who secures which nominations will go a long way toward deciding who may lead the state in the years to come.

>> Related: How does voting by political party work in Indiana?

Here are six key primary contests to watch on election night.

Governor

The race to be Indiana’s next chief executive has been perhaps the most noteworthy of the election cycle, with six Republicans bringing a variety of experience and outsider credentials to the competition.

Sen. Mike Braun has led in the polls from day one, including running up a 34 percentage-point lead in an April State Affairs/Howey Politics Indiana survey.

The other five candidates are: Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, former Attorney General Curtis Hill, Indianapolis mom Jamie Reitenour and two former state secretaries of commerce in Brad Chambers and Eric Doden.

The winner of Tuesday’s Republican primary will face Democrat and former state Superintendent of Public Instruction Jennifer McCormick, who will advance for her party unopposed.

Republican candidates spent tens of millions of dollars in an attempt to stand out in their crowded pack. The primary race also featured four televised debates, including a chaotic final display on April 24.

U.S. Senate

Two Democrats are vying for the chance to replace Braun in the U.S. Senate: Former state Rep. Marc Carmichael and Valerie McCray, a clinical psychologist.

Carmichael has outspent McCray in the race by a margin of nearly $63,000 to $15,000.

Both are attempting to become the state’s first Democratic senator since Joe Donnelly’s election in 2012.

Rep. Jim Banks is running unopposed in the Republican primary.

3rd Congressional District

Banks’ entry into the Senate race leaves his seat in Congress open, and a bevy of Republicans are seeking to replace him: Grant Bucher, Wendy Davis, Mike Felker, Jon Kenworthy, Tim Smith, Marlin A. Stutzman, Eric Whalen and Andy Zay.

State Affairs has identified Stutzman, a former congressman; Smith, a self-funding former Fort Wayne mayoral candidate; and Davis, a former Allen County judge, as candidates to watch in the crowded race.

Kiley Adolph and Phil Goss are running against one another in the Democratic primary.

5th Congressional District

After initially deciding against another run, Republican Rep. Victoria Spartz reversed course to seek re-election in 2024.

Eight other Republicans are running against Spartz: Raju Chinthala, Max Engling, Chuck Goodrich, Mark Hurt, Patrick Malayter, Matthew Peiffer, L.D. Powell and Larry L. Savage Jr.

Goodrich, a member of the Indiana House of Representatives, has spent more than $2 million on TV ads as he seeks to unseat Spartz, according to AdImpact.

Two Democrats, Ryan Pfenninger and Deborah A. Pickett, are on the ballot.

6th Congressional District

Seven Republicans are attempting to replace retiring Rep. Greg Pence: Jamison E. Carrier, Darin Childress, Bill Frazier, John Jacob, state Sen. Jeff Raatz, Jefferson Shreve and state Rep. Mike Speedy.

Shreve, who ran unsuccessfully for Indianapolis mayor in 2023, has spent nearly $4 million — predominantly through TV advertising — in his bid.

Cynthia Wirth, whom Pence defeated by 35 percentage points in 2022, is running unopposed in the Democratic primary.

8th Congressional District

Republican Rep. Larry Bucshon is also retiring, and a dozen candidates in both parties are seeking to fill his seat.

On the Republican side, former Rep. John Hostettler, state Sen. Mark Messmer, former President Donald Trump White House staff member Dominick Kavanaugh and frequent Bucshon primary challenger Richard Moss are each making a push.

Fellow Republicans Jim Case, Jeremy Heath, Luke Misner and Kristi Risk are also running but trail the above pack in campaign spending.

Four Democrats are also seeking a nomination: Erik Hurt, Peter FH Priest II, Edward Upton Sein and Michael Talarzyk.

Contact Rory Appleton on X at @roryehappleton or email him at [email protected].

State Republicans keep spending to protect House incumbents in primary

House Speaker Todd Huston expressed confidence Tuesday that Republican House members will prevail over challengers in next week’s primary. Nineteen of the 63 House Republicans seeking reelection this year are facing primary races. Those challenges have been lower-key than two years ago when about two dozen candidates seized on COVID-19 discontent and other issues in …