Stay ahead of the curve as a political insider with deep policy analysis, daily briefings and policy-shaping tools.

Request a DemoIndiana is on the cusp of mental health reform. But what about paying for it?

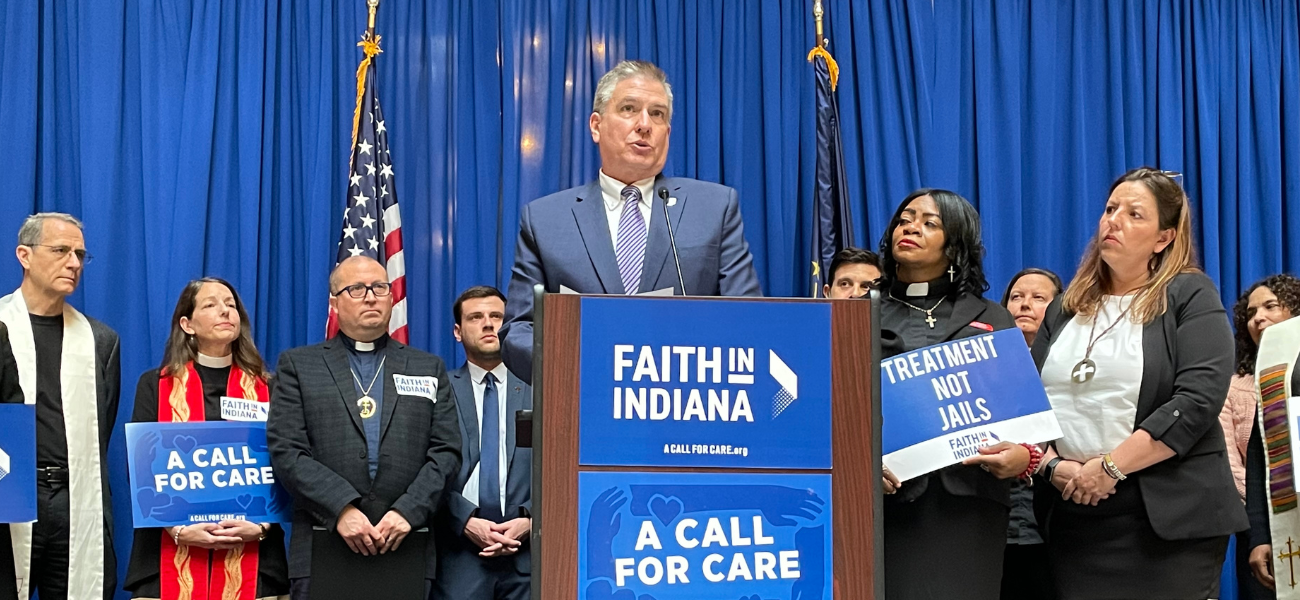

Rev. Rick Spleth, regional minister of Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), speaks during a Faith in Indiana press conference on March 7, 2023, inside the Statehouse. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

- Mobile crisis teams visit people at their homes in a new approach being hailed as transformative

- Advocates worry whether lawmakers will still consider fully funding the crisis system

- $1 cell phone surcharge floated as a possible way to fund an expanded system

A woman in rural Indiana wanted to harm herself. Without friends or family, she felt alone, like no one cared.

But on that day in February, a Logansport behavioral health clinic sent two members of its mobile team to the woman’s home. They convinced her to return to the clinic with them. She spoke with a therapist and learned about ongoing help available across Cass, Fulton, Miami and Pulaski counties.

“She started crying and said, ‘People really do care,'” recalls Bev Garrett, 54, who runs the mobile team at 4C Health. “That is the one thing that saved her life that day.”

Indiana has struggled to provide adequate care for people in crisis for years. As a result, suicides have remained above the national average. Indiana’s life expectancy, meanwhile, is lower than the national average and has been rapidly worsening over the last decade, fueled by excessive substance use.

It has grown so dire that drug overdoses have increased by more than 100% over 10 years, according to an analysis by an Indiana demographer, and the nonprofit Mental Health America last year said Indiana ranked 42nd in treatment.

So when Hoosiers reach a crisis point — whether they’re suicidal, experiencing delusions or desperate to shake the demons of addiction — Indiana provides the thinnest of a safety net. Two common destinations? An emergency room or a jail cell, both of which are costly.

Some parts of Indiana, though, are charging into a new frontier of delivering mental health services. Like 4C Health, they’re launching mobile teams to visit people at their homes. They’re establishing crisis stabilization units for people who can’t wait weeks for an appointment and are providing the services 24/7, regardless of anyone’s ability to pay.

The new ways of providing mental health services are being hailed as transformative.

“They are the single greatest developments in several decades of doing this work,” said Dr. Carrie Cadwell, CEO of 4C Health, which is funding the new services through temporary grant funding.

Now a collection of legislators, policymakers, providers, law enforcement, faith leaders and advocates are hoping to spread the crisis system across Indiana. By connecting the system with the state’s fledgling 988 hotline, Indiana could have a replica of 911, shifting mental health care away from law enforcement and into the hands of medical professionals and peers.

But in Indiana, there’s always a question about lawmakers’ appetite for adding an ongoing expense to the state budget. That’s especially true in a year when they are also considering significant investments into county public health departments.

Without help, the mental health system will undoubtedly continue to struggle. And worse, advocates say, new services provided by 19 clinics will recede as temporary grant funding runs dry.

Indiana lawmakers are grappling with a few questions: Will the state’s revenue forecasts in April reveal enough money to pay for the expansion? Should they instead pursue an option of adding a $1 surcharge on cell phone bills to generate new revenues? Should they increase the cigarette tax instead?

Or should they spend less and therefore save the problem for another day?

Creating a three-part crisis system

Just about everybody inside the Indiana Statehouse says that the state’s mental health system needs dramatic improvements. The price tag, though, begins at roughly $130.6 million per year.

According to a 2022 estimate by the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA), that’s how much it would cost each year to fully fund the three-part crisis system: the 988 hotline, mobile teams and crisis stabilization units.

If Indiana wants to gradually expand the number of clinics throughout the state, the price would increase in future years.

The push to fully fund the mental health system is led by some strong voices, including Sen. Michael Crider, R-Greenfield. He is a member of Senate Republican leadership and also serves on the Senate Appropriations Committee, which plays an outsized role in forming the state budget.

After the Behavioral Health Commission released its recommendations last fall, Crider filed Senate Bill 1 in an attempt to overhaul the system. The bill has already passed the Senate and has more than two dozen House sponsors.

But Crider will also need money in the budget to have a lasting impact.

A new model for mental health care

SB 1 would move Indiana from one model of mental health services — community mental health centers — to another: certified community behavioral health clinics (CCBHC).

To the layperson, the words may sound like a bureaucratic thesaurus. The impacts, however, have proven significant for clinics that have made the switch.

Put simply, the new model provides all-encompassing care. Among the more than 60 pages of federal criteria, for example, are requirements to provide access 24 hours a day. Waiting times have dropped and more people have received help in other states that have moved to the new model.

The new model also is expected to reduce overall spending in the state because, for example, a crisis stabilization unit is less costly than an emergency room. (Researchers say untreated mental illness accounts for $4.2 billion in annual costs in Indiana.)

4C Health in Logansport is witnessing the benefits. Funded by state and federal grants, the mobile team launched in September 2020 and has responded to nearly 3,000 calls for help across four largely rural counties.

On average, the mobile teams arrive within 25 minutes of calls. About 65% of the time, the mobile teams are stabilizing a Hoosier in crisis, which allows that person to remain safe at home.

The crisis stabilization unit — where someone can stay up to 23 hours — has accepted 228 voluntary admissions since it opened in February 2021. Some are walk-ins; some are dropped off by law enforcement or friends. None have required admission into a secure psychiatric facility.

As a result, the costlier psychiatric facility is now seeing a 24% drop in usage, which has amounted to about $1 million in savings, according to the clinic. And that doesn’t include any savings accrued by diverting people away from jails and emergency rooms.

Crider’s bill this session seeks to replicate those successes in every Indiana clinic.

“Those services can be developed in all parts of the state,” said Zoe Frantz, CEO of the Indiana Council of Community Mental Health Centers. “This is really an infrastructure bill for this whole state.”

Advocates say the new model is also more sustainable because the funding works differently. Right now, every service requires separate billing, and the state Medicaid reimbursement rates were set decades ago, which is a big contributor to the state’s difficulty in finding and retaining enough professionals to work in the mental health field.

But under the new model, clinics would be reimbursed by Medicaid for each patient per day and the scope of services would expand. That would allow patients to be treated no matter where they are: in their homes through mobile services, at a school or somewhere else.

Biden administration doesn’t do Indiana any favors

The new CCBHC model started taking root over the last seven years. Federal grants have helped specific clinics in several states, including some in Indiana, to begin providing the additional services found in the new model.

But those are patchwork and have limited funding.

The federal government, meanwhile, has approved 10 states to participate in what’s called a demonstration program. Those states are receiving a greater Medicaid reimbursement.

When Congress last year enabled an expansion of the demonstration program, several leaders in Indiana began preparing. Crider’s bill contained a provision encouraging Indiana FSSA to apply.

As a first step toward applying, Indiana sought a $1 million planning grant from the federal government.

Then last week, the Biden administration broke the hearts of a collection of Hoosiers. Not only did the federal government deny Indiana’s application for the grant, it also announced that 15 other states were under consideration for the demonstration program next year.

Indiana didn’t make the cut this round.

Without the federal funding, Indiana lawmakers could consider waiting until the next phase three years from now before seeking a mental health overhaul. But advocates say lawmakers need to act now.

“People are in crisis in Indiana today. And the state has already invested so much in planning their CCBHC implementation,” said Rebecca Farley David, senior advisor at the National Council for Mental Wellbeing. “There are still options remaining to them. They can still do this.”

Crider’s bill would allow FSSA to pursue those other options. Indiana could apply for what’s called a Medicaid state plan amendment, as a handful of other states have done. It would still transform Indiana’s mental health system and allow for greater services through the use of Medicaid, but the option does not carry additional federal funding — at least not until Indiana is accepted into the demonstration program.

Advocates and providers, meanwhile, remain worried. Will lawmakers still consider fully funding the crisis system?

A federal grant enabled Southwestern Behavioral Healthcare in Evansville to launch a mobile team and develop a crisis stabilization unit in early 2022. Southwestern has seen more than 4,200 interventions, including calls to its crisis line.

“The hope is that there’ll be some continuous, sustainable, reliable funding that can fund this crisis system in Indiana. Because my grant will run out, and then what?” said Katy Adams, CEO of the center. “We just have to believe that people are going to back it. If they don’t, it’ll be catastrophic.”

Voices calling for change

Supporters of the new crisis system are uniting around SB 1 while urging lawmakers to include funding for the three-part crisis system.

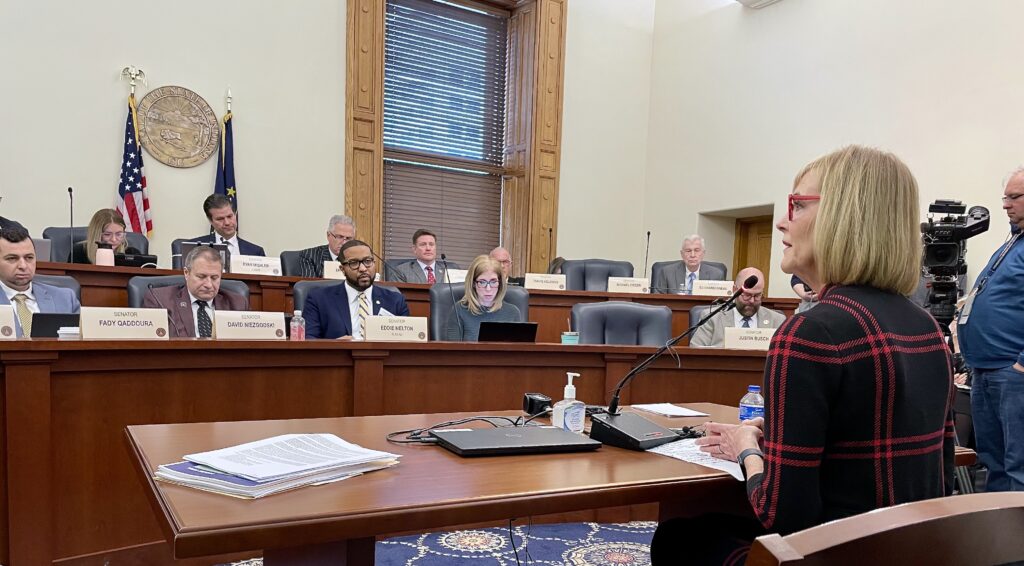

Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, who is running for governor, took the rare step of testifying in front of a Senate committee in January. She spoke about members of her family who have faced depression, alcoholism, bipolar disorder and suicide.

“I know that we’re in a position here in the General Assembly where we can make a difference and we can help Hoosiers,” Crouch told State Affairs afterward. “And that’s what Senate Bill 1 will do.”

More recently, on WFYI’s show “Indiana Lawmakers,” Crouch said she wanted to see the full $130.6 million in the budget.

Dr. Jerome Adams, the former Indiana health commissioner who served as U.S. surgeon general under former President Donald Trump, wrote an IndyStar op-ed in support of the bill. He wrote about a family member struggling with substance use disorder.

Law enforcement leaders are also on board. Indiana Sheriffs’ Association Executive Director Stephen Luce testified before the Senate and sent a letter of support to community organizers at the nonprofit Faith in Indiana: “For years, the jails have been the dumping ground for those in need of mental health services. It is time to fund mental health properly in our communities for those in need to have access to treatment.”

Faith in Indiana leaders held a rally in February that attracted several hundred supporters, including a bipartisan group of Indiana lawmakers. They have followed up with multiple meetings and press conferences inside the Statehouse.

They see what’s been promised by Indiana officials so far. Gov. Eric Holcomb plans to pilot four mobile crisis teams to cover 15 counties in 2023, and he aims to fund multiple crisis centers to pilot that approach, too.

But advocates are growing tired of pilot programs.

“This system requires full funding so that our people have the help they need when they are in crisis,” several Faith in Indiana leaders wrote to Holcomb and lawmakers in a March 7 letter. “We are looking to you to provide the leadership we need to have safe and caring communities.”

$1 cell phone surcharge to pay for it?

How to pay for expanded mental health care remains up in the air.

Citing a Behavioral Health Commission recommendation, Crider suggests a monthly $1 surcharge on cell phone bills. FSSA estimates it would raise roughly $90 million, covering nearly 70% of the costs associated with an expanded mental health system.

Crider likes it, in part, because the surcharge contains federal restrictions that require the money to be spent specifically on 988 calls and responses to those calls.

Most supporters and advocates seem to agree with the surcharge — noting that 911 is funded similarly — but some are looking to other options.

The Indiana Chamber of Commerce is urging lawmakers to consider an increased tax of $2 per pack of cigarettes and similar taxes on other tobacco and vaping products. The Chamber, which has unsuccessfully pushed for similar increases for years, estimates the taxes would fund the mental health and public health systems.

House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, said he doesn’t think the state needs new revenues to meet the funding goal, though he has yet to publicly specify what amount he would support.

“I don’t think we need to go find an alternative funding source,” Huston told reporters March 9. “I think we can find the money.”

In the Senate, President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, has yet to publicly endorse a specific number or way of paying for it. He has repeatedly noted that the mental health program is a priority for his caucus, so much so that they agreed to highlight it as this session’s first bill.

“We have long been trying to find a way to get some revenue to support those programs, which I think are super, super important,” Bray told reporters March 16. “Part of it is going to be what the final [revenue] forecast looks like. And we are really fortunate in Indiana; Hoosiers are hard at work and that’s creating revenue through the income tax, sales tax, and all the avenues that we have. So is it possible that we could do that without a new revenue source? I’d love that.”

The version of the budget that passed the House did not contain funding to support the crisis system. Huston and the top budget writer, Rep. Jeff Thompson, R-Lizton, said they wanted to give their Senate colleagues an opportunity to request the amount they find necessary.

They did, however, set aside $10 million in grants to provide mental health services for incarcerated Hoosiers — a priority of House Republicans this year to help alleviate the state’s jail overcrowding crisis.

Budget negotiations between the two chambers could last weeks. The House’s proposed budget is now in the hands of the Senate Appropriations Committee, which includes Crider and other supportive voices.

“I’ll be in there at the end,” Crider told State Affairs, “fighting for funding.”

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, which has trained listeners standing by and ready to help. Visit 988lifeline.org for crisis chat services or for more information. Visit the Indiana Suicide Prevention website for resources.

Contact Ryan Martin on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, or at [email protected].

Twitter @stateaffairsin

Facebook @stateaffairsin

Instagram @stateaffairsin

LinkedIn @stateaffairs

Header image: Rev. Rick Spleth, regional minister of Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), speaks during a Faith in Indiana press conference on March 7, 2023, inside the Statehouse. (Credit: Ryan Martin)

4 things to know about Braun’s property tax proposal

Sen. Mike Braun, the Republican candidate for Indiana’s governor, released a plan for overhauling property taxes Friday morning that would impact millions of Hoosiers, Indiana schools and local governments. “Nothing is more important than ensuring Hoosiers can afford to live in their homes without being overburdened by rising property taxes driven by rapid inflation in …

Bureau of Motor Vehicles looks to add new rules to Indiana’s driving test

The Bureau of Motor Vehicles wants to amend Indiana’s driving skills test, putting “existing practice” into administrative rule. Indiana already fails drivers who speed, disobey traffic signals and don’t wear a seatbelt, among other violations. Yet the BMV is looking to make the state’s driving skills test more stringent. A proposed rule amendment looks to …

In Indianapolis, Harris says she’s fighting for America’s future

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, told a gathering of women of color in Indianapolis on Wednesday that she is fighting for America’s future. She contrasted her vision with another — one she said is “focused on the past.” “Across our nation, we are witnessing a full-on assault on hard-fought, hard-won freedoms …

Indiana Black Legislative Caucus endorses Harris, pledges future support

The Indiana Black Legislative Caucus unanimously voted Wednesday to endorse Vice President Kamala Harris’ presidential run and will look at ways to assist her candidacy, the caucus chair, state Rep. Earl Harris Jr., D-East Chicago, told State Affairs. The caucus is made up of 14 members of the Indiana General Assembly, all of whom are …